The Hollywood Star and Studio Systems - Part One

Gallery 1: Columbia Pictures and Hollywood in the 1950s

Gallery 2: Columbia Pictures - Films and Stars

Gallery 3: The Star and Studio Systems as experienced by Tab Hunter and Robert Wagner

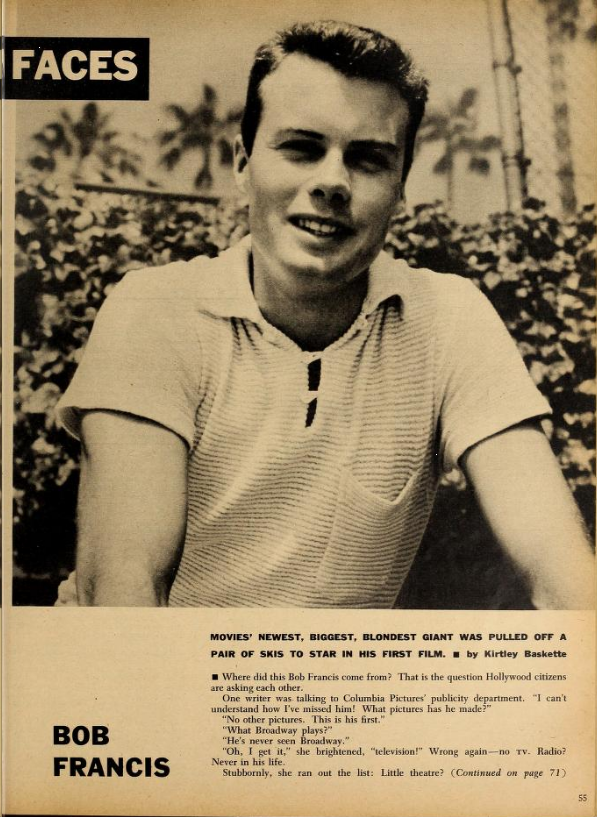

Gallery 4: Robert Francis’ Rise from Unknown to Star as documented in photographs and stories from 1953 and 1954

By July 4, 1949, when Bob Francis was discovered (or when he discovered being a film actor might be a career option), the Hollywood Studio System had already received a death blow: a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court anti-trust decision forced the studios to separate their film production activities and their exhibition activities (block booking of their own productions in their own theaters). The decision especially affected the Big Five (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount Pictures, RKO Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Warner Brothers) which had vast production studios, distribution divisions, nationwide theater chains, and numerous contracts with actors and filmmakers. The Little Three (Columbia Pictures, Universal Pictures, United Artists) had few, if any, theaters and were less affected. The second death blow came from television sets in the homes of millions people who no longer felt the need to leave their homes two or three times each week and go to the movies.

The lethal nature of these changes played out over a decade or two with studios not renewing contracts with actors (many of whom formed their own independent companies) and producing television programs in addition to movies. These changes in turn created the need for more adjustment and accommodation — and thus, today’s Hollywood Moguls are independent filmmakers and agents who can package stars, directors, writers, etc., for a particular film and specifically targeted audiences. Today’s stars and sometimes celebrities, often famous for being infamous, must invent and re-invent themselves without much attention to long-term career goals and without much guidance from long-time and loyal “starmakers” associated with a studio and its commitment to profitability.

"It wasn't good entertainment and it wasn't art, and most of the movies produced had a uniform mediocrity, but they were also uniformly profitable ... The million-dollar mediocrity was the very backbone of Hollywood."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Studio_system

Gallery 1: Columbia Pictures and Hollywood in the 1950s

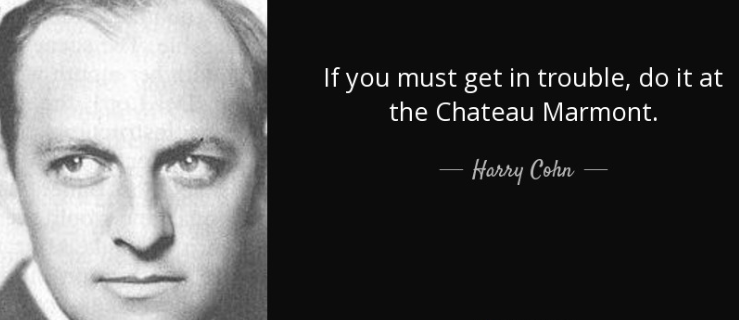

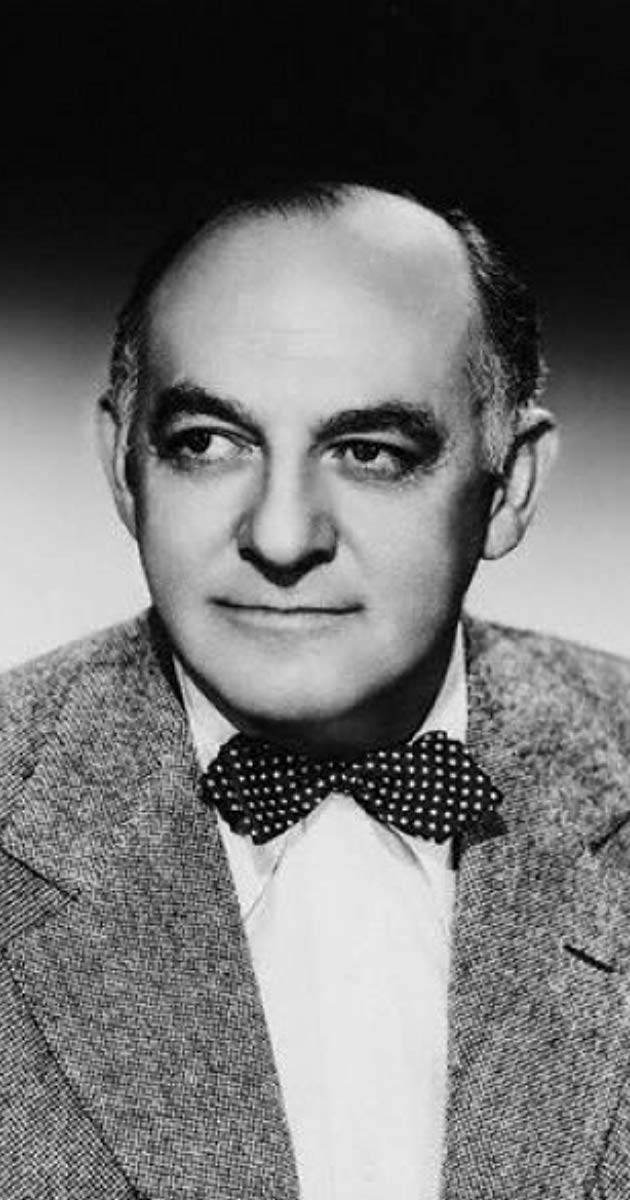

Above: Harry Cohn (July 23, 1891–Feb. 27, 1958), Co-Founder, President, and Production Director, Columbia Pictures

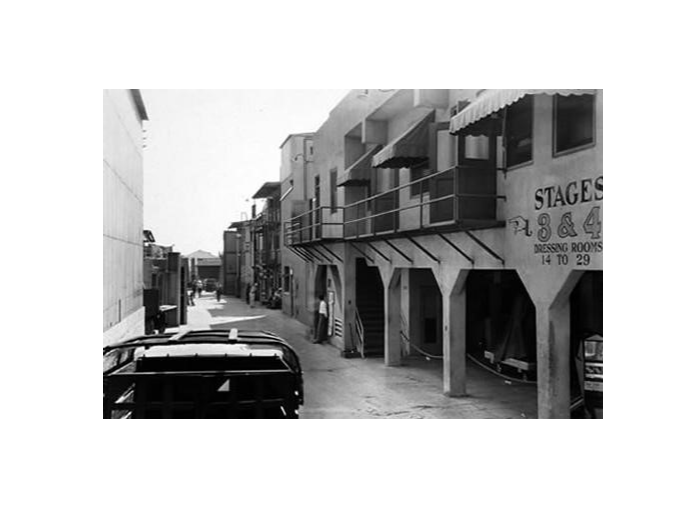

Below: Two historical photographs made at Columbia Pictures

Below: When Bob was born in 1930, the HOLLYWOODLAND sign was seven years old.

Erected in 1923, its purpose was to advertise the name of a new segregated housing development in the hills above the Hollywood district of Los Angeles.

Real estate developers Woodruff and Shoults called their development "Hollywoodland" and advertised it as a "superb environment without excessive cost on the Hollywood side of the hills."

They contracted the Crescent Sign Company to erect thirteen south-facing letters on the hillside. The sign company owner, Thomas Fisk Goff (1890–1984), designed the sign. Each letter was 30 ft (9.1 m) wide and 50 ft (15.2 m) high, and the whole sign was studded with around 4,000 light bulbs. The sign flashed in segments: "HOLLY," "WOOD," and "LAND" lit up individually, and then as a whole. Below the Hollywoodland sign was a searchlight to attract more attention. The poles that supported the sign were hauled to the site by mules. The project cost $21,000, equivalent to $320,000 in 2019.

Over the course of more than half a century, the sign, designed to stand for only 18 months, sustained extensive damage and deterioration.

By 1949, when Bob first became a regular visitor in Hollywood, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce began a contract with the City of Los Angeles Parks Department to repair and rebuild the sign. The contract stipulated that "LAND" be removed to spell "Hollywood" and reflect the district, not the "Hollywoodland" housing development. The Parks Department dictated that all subsequent illumination would be at the Chamber's expense, so the Chamber opted not to replace the lightbulbs. The 1949 effort gave it new life, but the sign's unprotected wood-and-sheet-metal structure continued to deteriorate. By the 1970s, the first O had splintered and broken, resembling a lowercase u, and the third O had fallen down completely, leaving the severely dilapidated sign reading "HuLLYWO D."

In 1978, in large part because of the public campaign to restore the landmark by Hugh Hefner, founder of Playboy magazine, the Chamber set out to replace the severely deteriorated sign with a more permanent structure. Nine donors gave $27,778 each (totaling $250,000) to sponsor replacement letters, made of steel supported by steel columns on a concrete foundation.

The new letters were 45 ft (13.7 m) tall and ranged from 31 to 39 ft (9.4 to 11.9 m) wide. The new version of the sign was unveiled on November 11, 1978, as the culmination of a live CBS television special commemorating the 75th anniversary of Hollywood's incorporation as a city.

Refurbishment, donated by Bay Cal Commercial Painting, began again in November 2005, as workers stripped the letters back to their metal base and repainted them white.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hollywood_Sign offers a detailed account of the history of the iconic sign.

Below: As Bob traveled to Columbia Pictures at the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street for the first time in 1953, he could see the newly refurbished HOLLYWOOD sign. This photograph is c. 2014.

Below: During the two years Bob’s career was developing, he almost daily traveled from Pasadena to Columbia Pictures in Hollywood. In the last months of his life, after moving into an apartment on Hayworth Street just a few miles west of the studio, he also saw familiar Hollywood landmarks. Most of the following photographs were made during those years.

Brown Derby https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_Derby

The first restaurant opened in February 1926 at 3427 Wilshire Boulevard in a building built in the distinctive shape of a derby hat.

Despite its less distinctive Spanish Mission style facade, the second Brown Derby, which opened on Valentine’s Day 1929 at 1628 North Vine Street in Hollywood, was the branch that played the greater part in Hollywood history. Due to its proximity to movie studios, it became the place to do deals and be seen.

Clark Gable is said to have proposed to Carole Lombard there. Rival gossip columnists Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper are recorded as regular patrons.

The Hollywood Brown Derby is the purported birthplace of the Cobb salad, which was said to have been hastily arranged from leftovers by owner Bob Cobb for showman and theater owner Sid Grauman. It was chopped fine, because Grauman had just had dental work done, and couldn't chew well.

According to Shirley Temple, the non-alcoholic drink bearing her name was invented at the Brown Derby in the mid-1930s. Temple herself never liked the drink and noted her personality rights had been used without permission.

The Hollywood Brown Derby closed for the last time at its original site on April 3, 1985, as a result of a lease dispute.

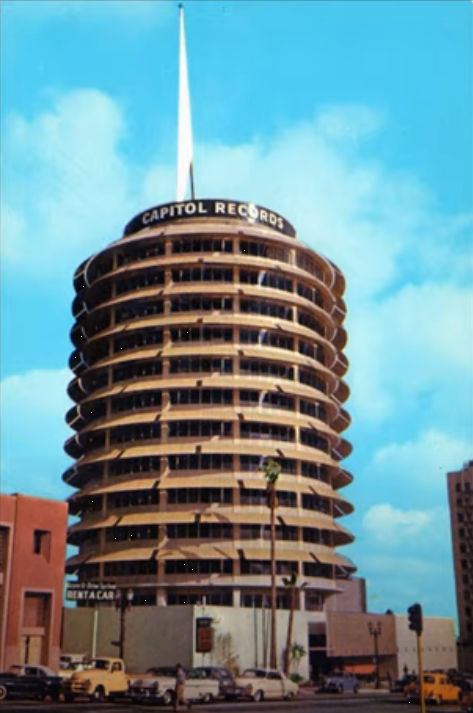

Below: The Capitol Records Building, also known as the Capitol Records Tower, was under construction at the time of Bob’s death. It is a 13-story tower building designed by Louis Naidorf of Welton Becket Associates, one of the city's landmarks. Construction began soon after British music company EMI acquired Capitol Records in 1955, and was completed in April 1956. Located just north of the Hollywood and Vine intersection, the Capitol Records Tower houses the consolidation of Capitol Records' West Coast operations and is home to the recording studios and echo chambers of Capitol Studios. The building is a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument and sits in the Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District. It has been described as the "world's first circular office building."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitol_Records_Building

Below: Grauman's Chinese Theatre is a movie palace on the historic Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6925 Hollywood Blvd. in Hollywood. The original Chinese Theatre was commissioned following the success of the nearby Grauman's Egyptian Theatre, which opened in 1922. Both are in Exotic Revival style architecture. Built by a partnership headed by Sid Grauman over 18 months starting in January 1926, the theater opened May 18, 1927, with the premiere of Cecil B. DeMille's The King of Kings. It has since been home to many premieres, as well as birthday parties, corporate junkets, and three Academy Awards ceremonies. Among the theatre's most distinctive features are the concrete blocks set in the forecourt, which bear the signatures, footprints, and handprints of popular motion picture personalities from the 1920s to the present day.

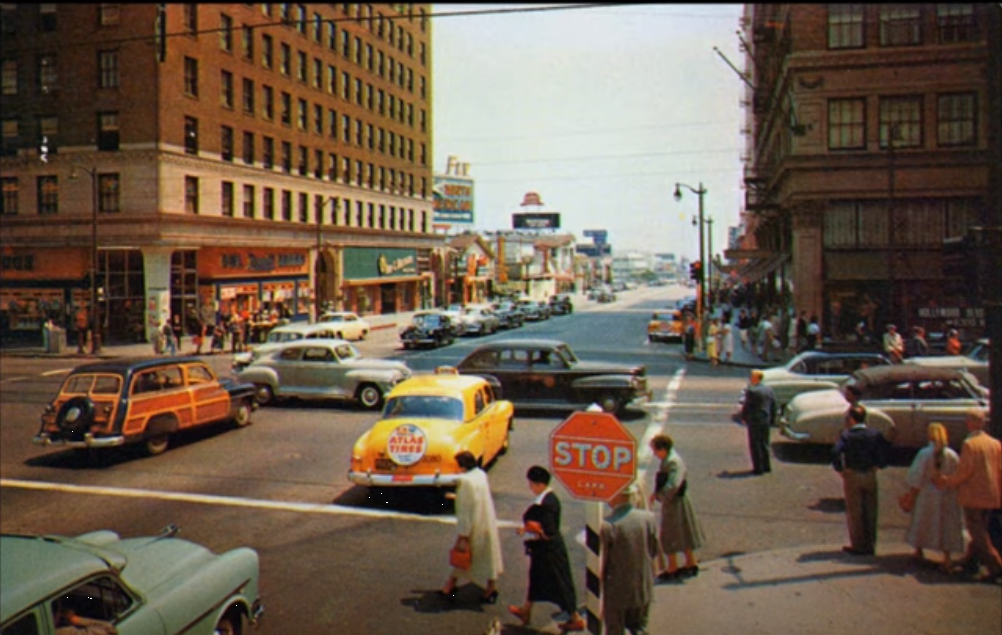

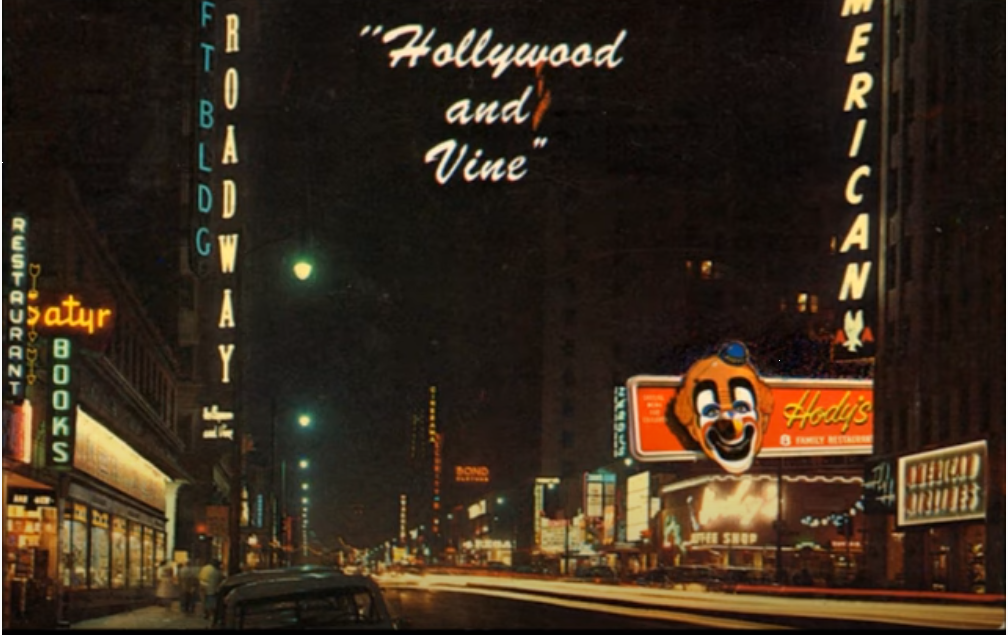

Below: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street, 1952

Below: The Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel is a historic hotel located at 7000 Hollywood Boulevard in Hollywood, across the street from Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. It opened on May 15, 1927, and is the oldest continually operating hotel in Los Angeles.

The hotel was built in 1926, in what is known as the Golden Era of Los Angeles architecture, and was named after the 26th president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt. It was financed by a group that included Louis B. Mayer, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and Sid Grauman. It cost $2.5 million ($36.8 million today) to complete and opened on May 15, 1927.

The first Academy Awards ceremony was held at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on May 16, 1929, inside the Blossom Ballroom. A private ceremony open only to Academy members, it was hosted by Academy president Douglas Fairbanks and held three months after the winners were announced, with 270 people in attendance. At the time, the "Oscar" nickname for the award had not yet been invented (the nickname would be introduced four years later).[

The Gable-Lombard penthouse, a 3,200 square-foot duplex with an outdoor deck with views of the Hollywood Hills and the Hollywood sign, is named for Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, who used to stay in the room for five dollars a night. The Marilyn Monroe suite is named for the actress, who lived at the hotel for two years early in her career.

Photo c. 1954

Below: Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Street, 1952, looking east from area near Grauman’s Chinese Theater and the Roosevelt Hotel.

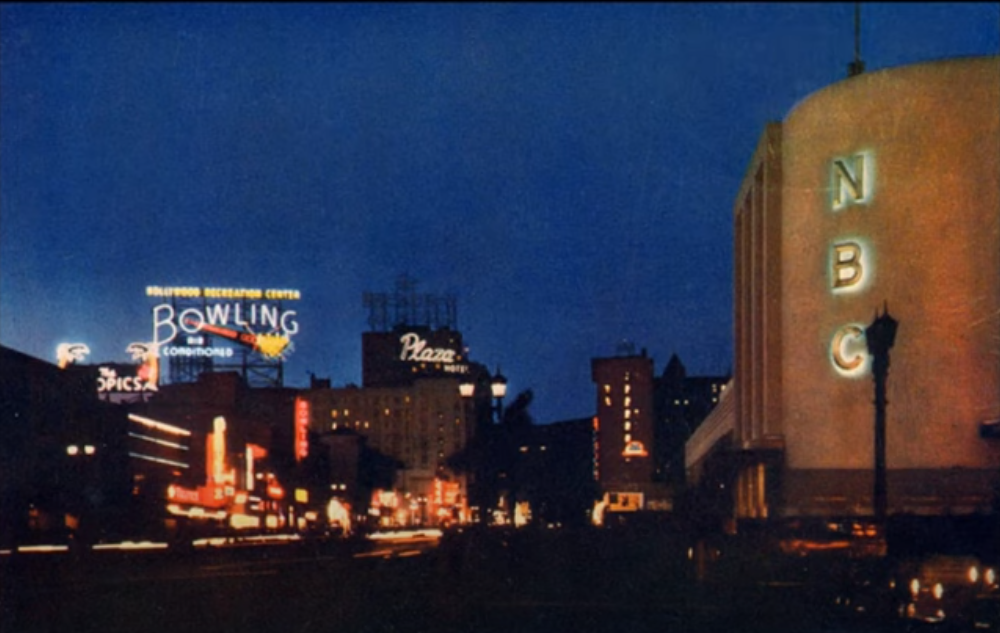

Below: NBC at intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Vine Street, early 1950s

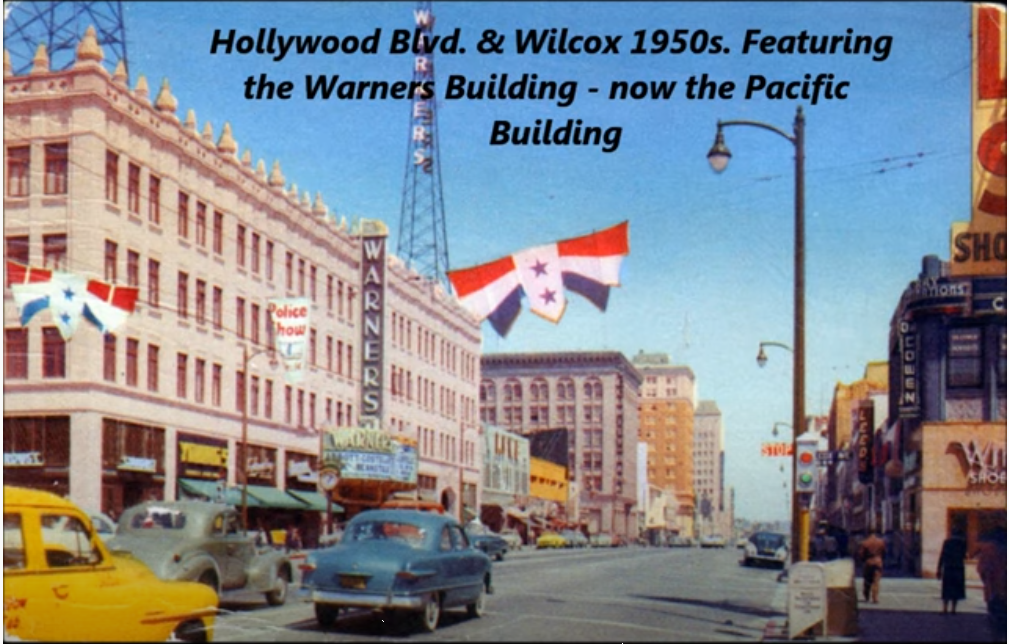

Below: Hollywood Boulevard and Wilcox Avenue

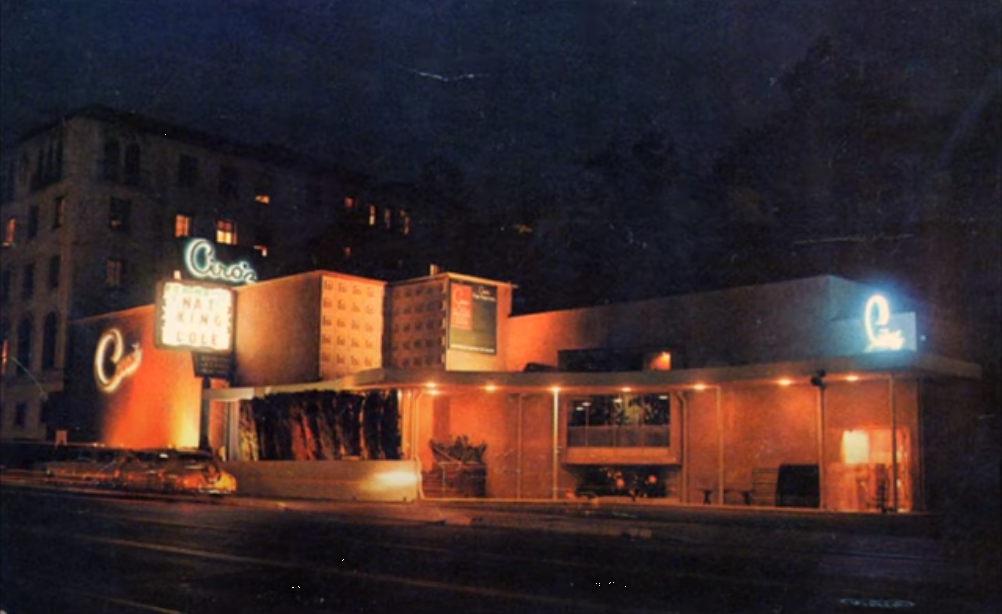

Below: Ciro's opened in January 1940 by entrepreneur William Wilkerson at 8433 Sunset Boulevard. Wilkerson also opened Cafe Trocadero, in 1934, and the restaurant La Rue, both on the Strip, and later originated The Flamingo in Las Vegas, only to have control of the resort wrested from him by mobster Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel. Herman Hover took over management of Ciro's in 1942 until it closed its doors in 1957. Hover filed for bankruptcy in 1959, and Ciro's was sold at public auction for $350,000. Ciro's combined a luxe baroque interior and an unadorned exterior and became a famous hangout for movie people of the 1940s and 1950s. It was one of the places to be seen and guaranteed being written about in the gossip columns of Hedda Hopper, Louella Parsons, and Florabel Muir.

Among the galaxy of celebrities who frequented Ciro's were Marilyn Monroe, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, James Dean, Ava Gardner, Sidney Poitier, Anita Ekberg, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Joan Crawford, Betty Grable, Marlene Dietrich, Ginger Rogers, Ronald Reagan, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Mickey Rooney, Cary Grant, George Raft, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Judy Garland, June Allyson and Dick Powell, Mamie Van Doren, Jimmy Stewart, Jack Benny, Peter Lawford, and Lana Turner (who often said Ciro's was her favorite nightspot) among many others. During his first visit to Hollywood in the late 1940s, future President John F. Kennedy dined at Ciro's.

Below: Coffee Dan’s at Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Street. In Bob’s time Coffee Dan’s was open 24 hours, seven days per week. Now it is a McDonald’s.

Below: Hody’s Family Restaurant at Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street

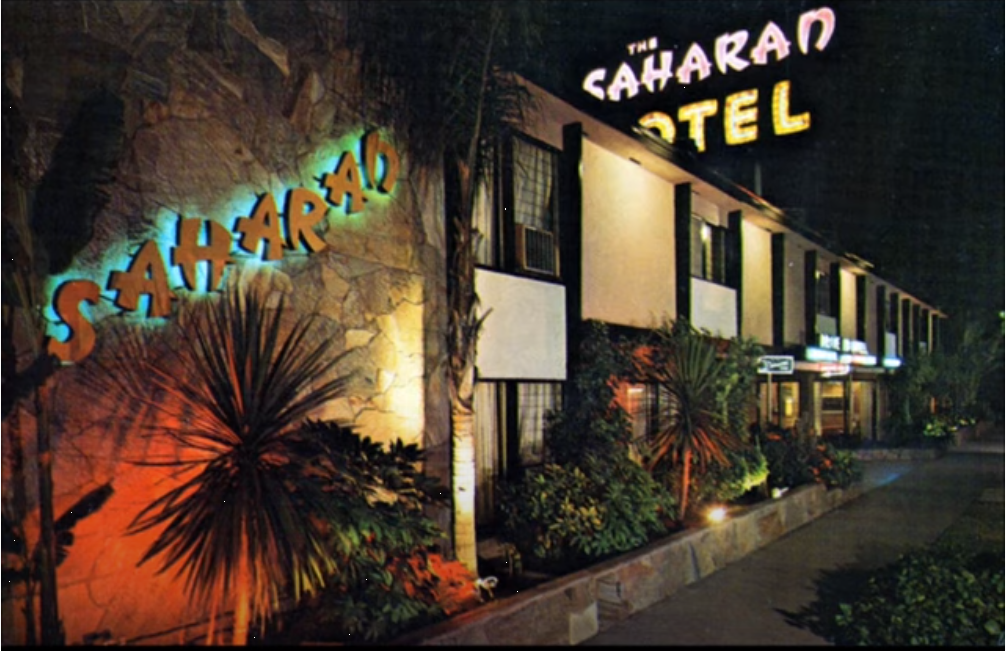

Below: Saharan Motel Sunset Boulevard and Alta Vista Boulevard

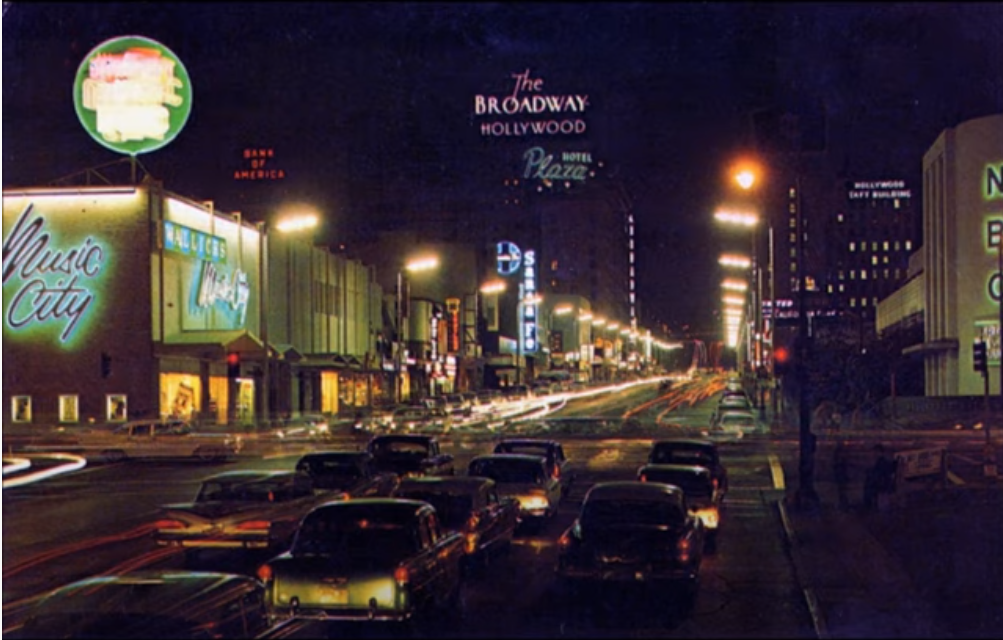

Below: Sunset Boulevard and Vine Street

Below: Sunset Boulevard and Vine Street

Gallery 2: Columbia Pictures - Films and Stars

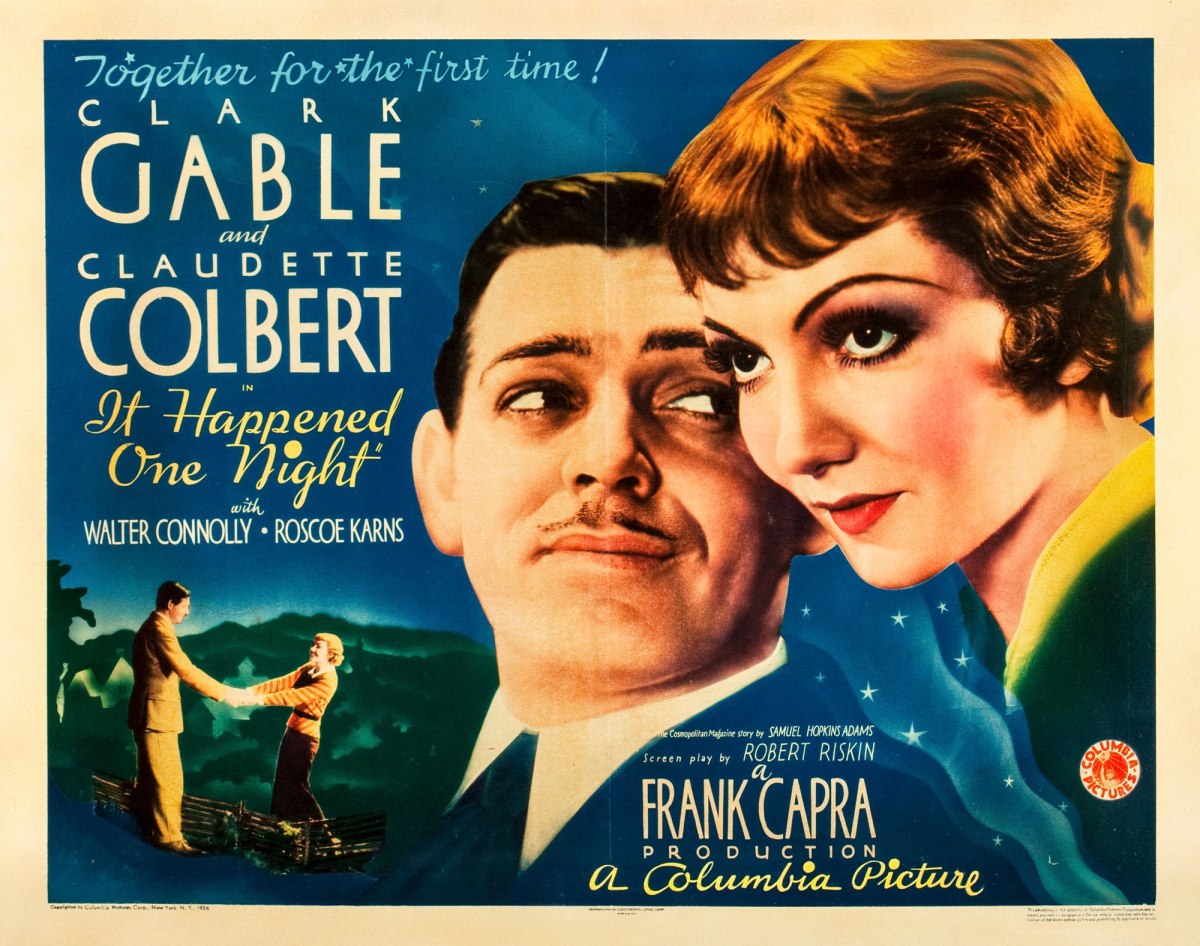

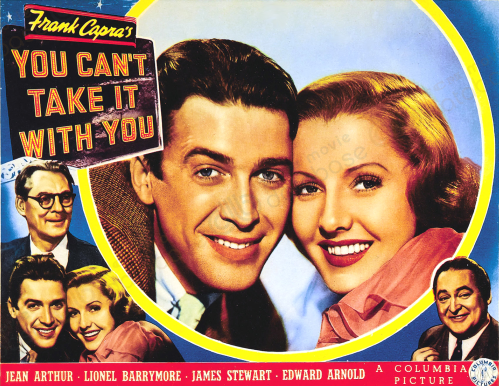

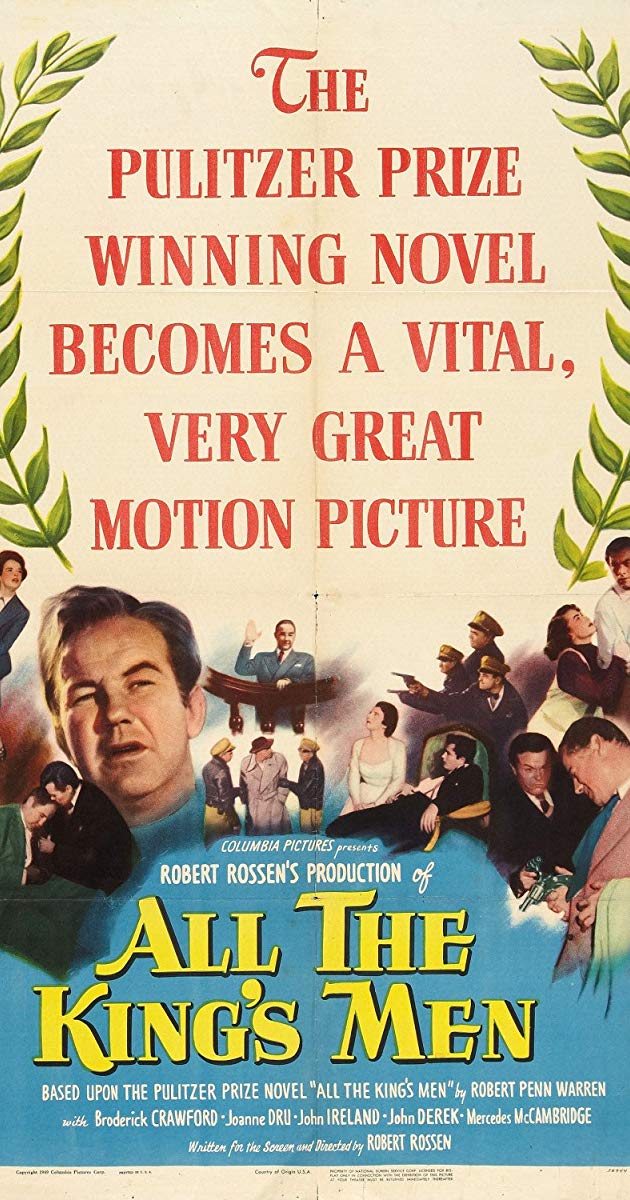

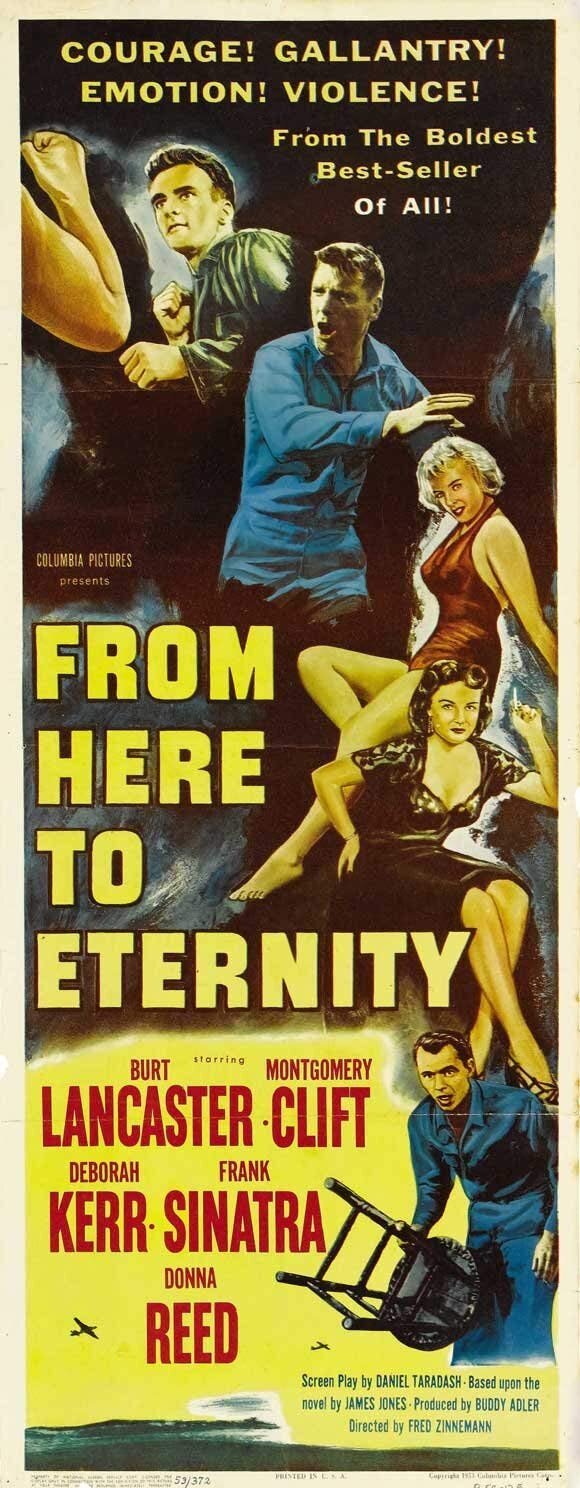

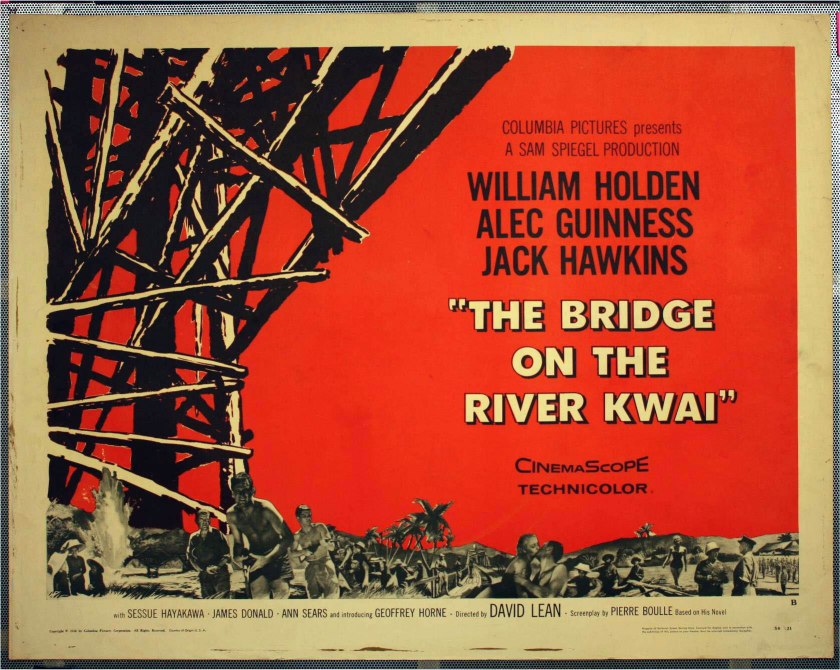

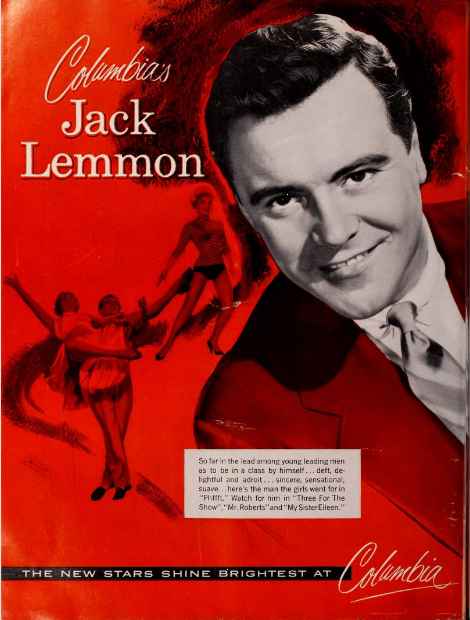

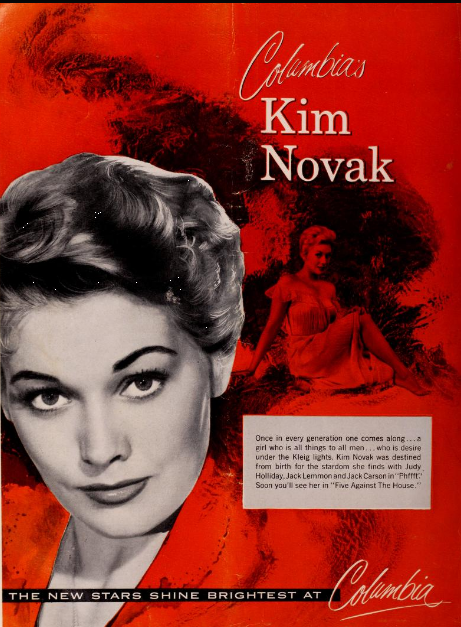

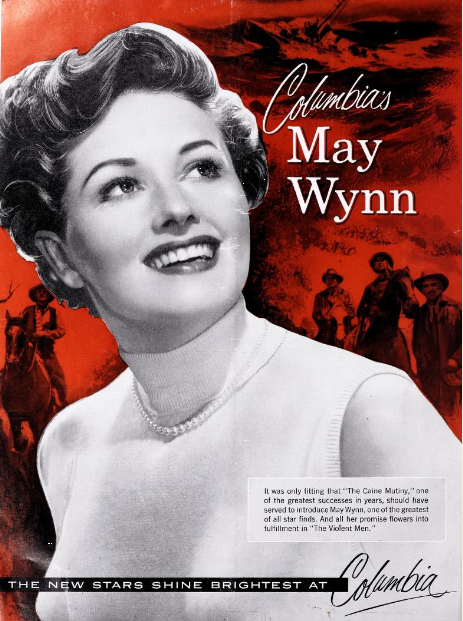

In addition to its many serials and series (The Three Stooges, “Gower Gulch” Westerns, Boston Blackie, Gene Autry Westerns, Blondie, Jungle Jim), Columbia also produced major artistic and box office hits: Lady for a Day (1933), It Happened One Night (Best Film Oscar, 1934), One Night of Love (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Lost Horizon (1937), The Awful Truth (1937), You Can’t Take It With You (Best Film Oscar, 1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941), The Invaders (1942), The Talk of the Town (1942), The More the Merrier (1943), All the King’s Men (Best Film Oscar, 1949), Born Yesterday (1951), The Happy Time (1952), From Here to Eternity (Best Film Oscar, 1953), The Caine Mutiny (1954), On the Waterfront (Best Film Oscar, 1954), Picnic (1956), The Solid Gold Cadillac (1956), Pal Joey (1957), The Bridge On the River Kwai (Best Film Oscar, 1957)…. In slim artistic years, Columbia had box office success with its roster of stars: Rita Hayworth (its biggest star), Glenn Ford, William Holden, Judy Holliday, Kim Novak, as well as The Three Stooges, Ann Miller, Evelyn Keyes, Jack Lemmon, Barbara Hale, Larry Parks, and Lucille Ball.

Glenn Ford, c. late 1940s

Rita Hayworth, c. 1946

William Holden, c. late 1940s

Judy Holliday, c. 1950 (Best Actress Oscar for Born Yesterday, 1950)

Jack Lemmon, c. 1950s

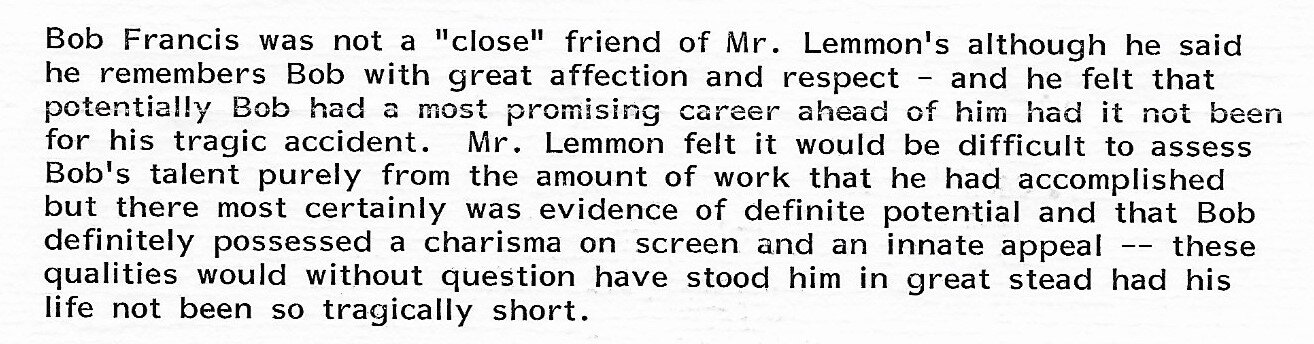

Janet McCauley, Vice President, Jalem Productions, letter, Sept. 2, 1993. Jalem Productions was Lemmon’s own company.

Kim Novak, c. early 1950s

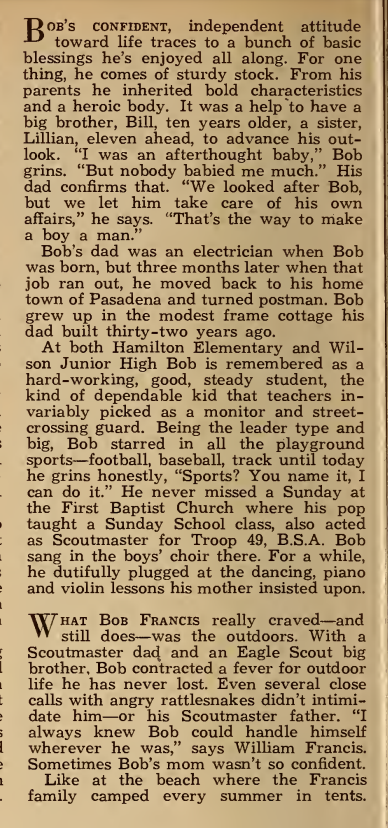

But in the early 1950s enough of the Star and Studio Systems remained in place to continue “…creating, promoting, and exploiting…promising young actors” who might be glamorized and given personae with new names and backgrounds. “The Star System put emphasis on the image rather than the acting, although discreet acting, voice, and dancing lessons were a common part of the regiment.”

Everyone employed by a studio, especially public relations personnel, worked to create a star persona and generate publicity. The studios also sought to cover up incidents or lifestyles that could damage a public image. Fan magazine writers and editors, private detectives, lawyers, and police officers were part of a vast network that aided and abetted the studios in both the manufacturing and protecting (sometimes from themselves) of movie stars and contract players.

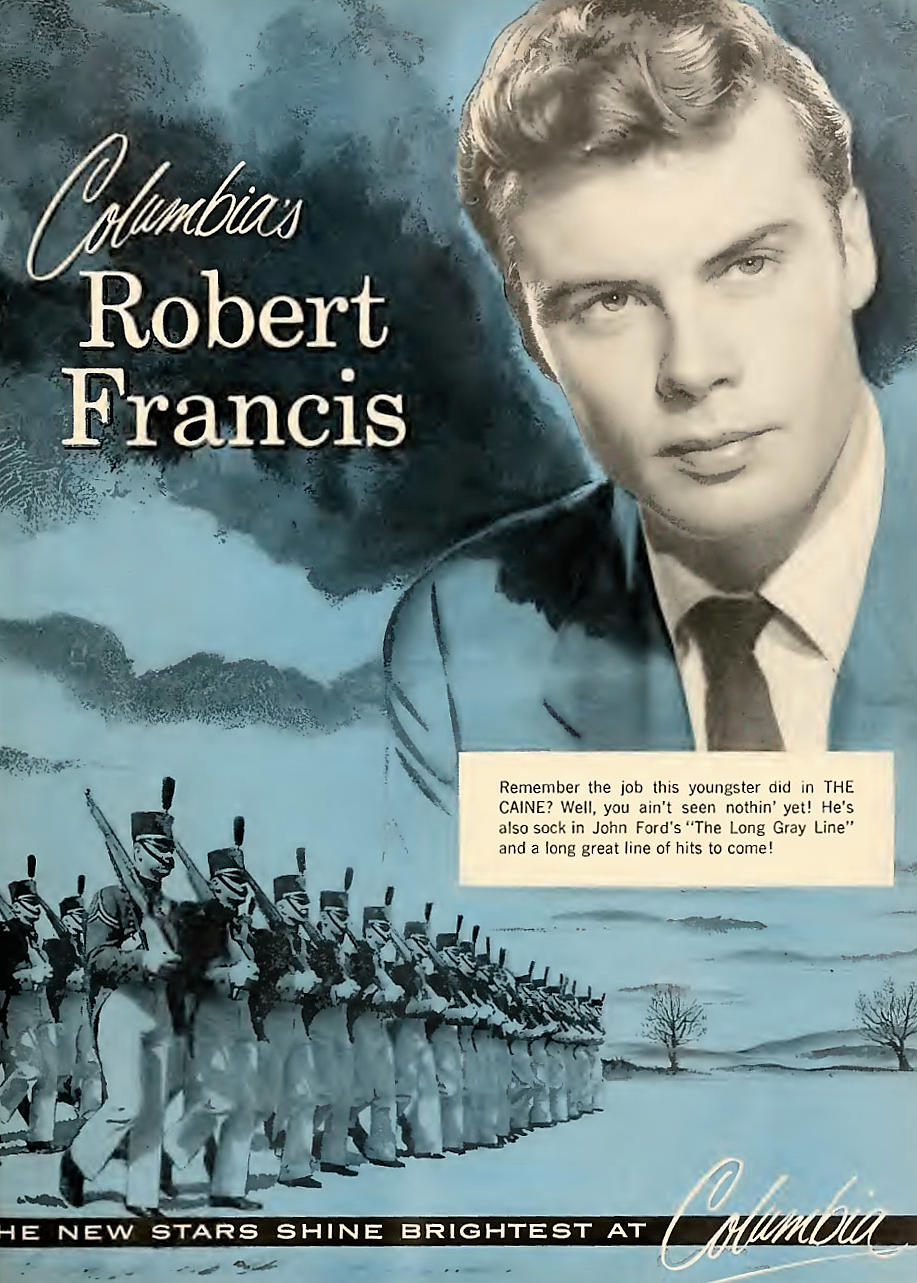

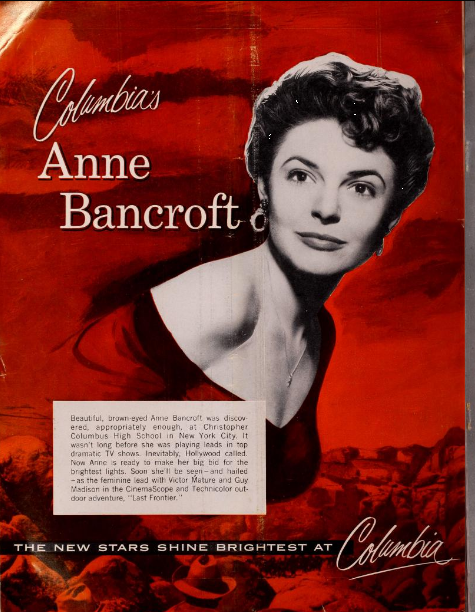

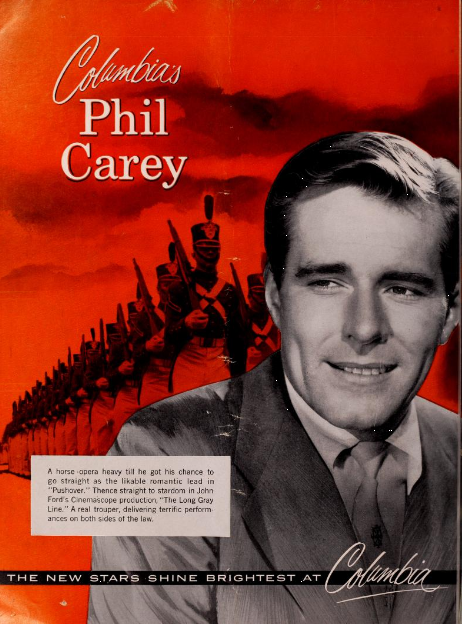

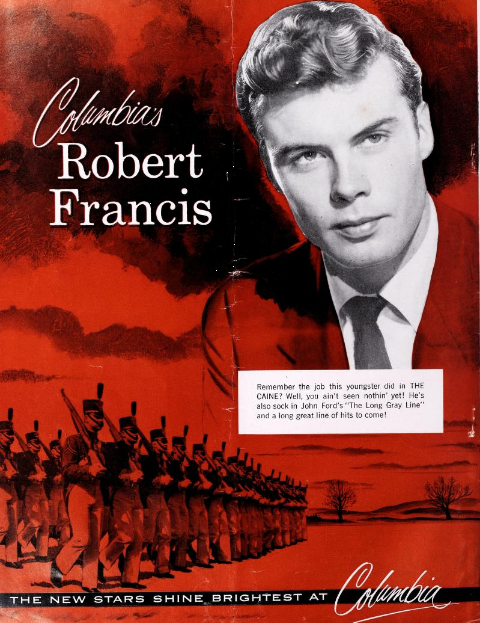

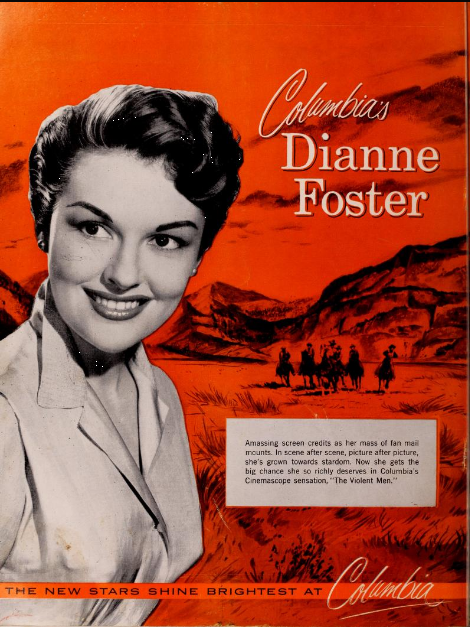

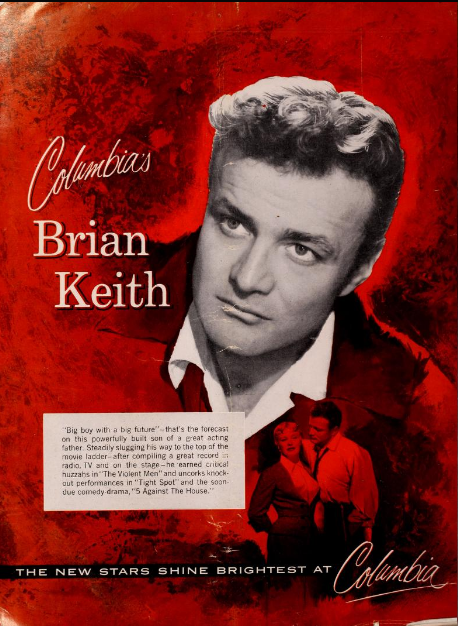

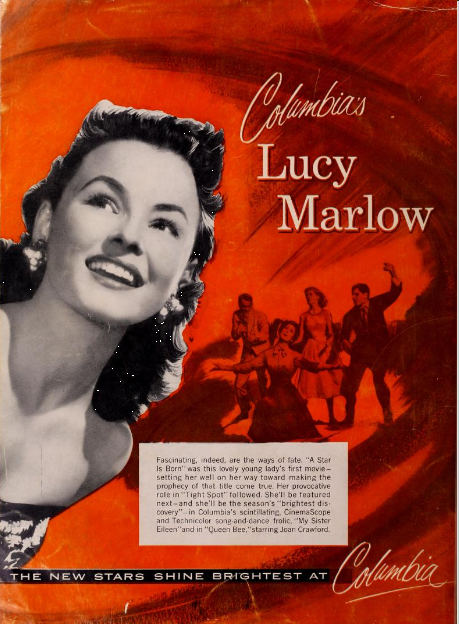

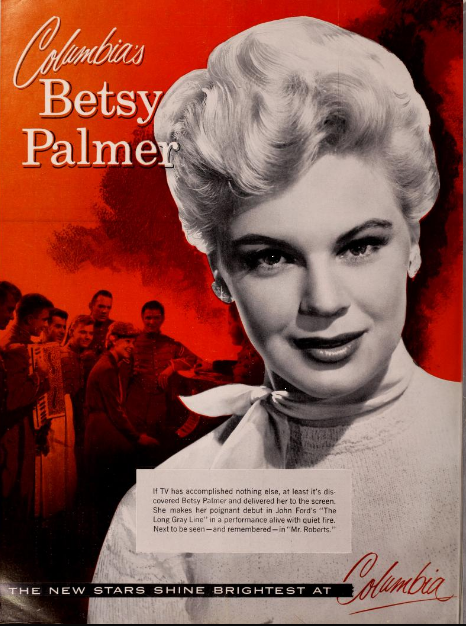

Bob was in a group of young actors in Columbia’s “class of 1954-1955,” contract players that Columbia hoped over time would join the ranks of movie stars and accomplished actors created by the Star System. During 1954 and 1955 Columbia promoted its future stars in full-page, back cover ads in Motion Picture Herald, a weekly trade magazine focused mostly on marketing activities and achievements by movie exhibitors. Bob was featured twice, once in blue and once in orange. The success of these actors varied — Bancroft left Hollywood for Broadway and then returned to score an Oscar, Carey and Keith achieved fame in long-run television shows, Lemmon received two acting Oscars, Novak was enormously popular for several years and appeared in hit movies but then became somewhat elusive personally and professionally. Foster, Marlow, and Wynn found some success and longevity in films and television, but did not become major film stars. Bob and Wynn were featured in photo stories in fan magazines. He and Marlow also had at least one photo story shoot (documented on this website). Columbia also promoted Aldo Ray and Cleo Moore during this time period. Bob and Ray did a photo story that also featured Lemmon. Bob “dated” Moore to at least one major Hollywood function in early 1955.

“…The studio system could be emotionally difficult, because I wasn’t the only hopeful juvenile leading man being groomed for a career. There were dozens at each studio, all starting out at $75 a week, all more or less good looking, all more or less types who could conceivably replace an older leading man who was already at the studio…One of the small tortures of the way the studios operated was that there were plenty of other people who were something like you. Every time you looked around, you saw someone who was a living, breathing implication that you were replaceable. And the sad fact was that you were.” (Wagner, pp. 48-49)

Motion Picture Herald, published from 1931 to December 1972, by Quigley Publishing Company owned by Martin Quigley.

Phil Carey appeared with Bob in They Rode West and The Long Gray Line.

Dianne Foster appeared with Bob in The Bamboo Prison.

Brian Keith appeared with Bob in The Bamboo Prison.

Betsy Palmer appeared with Bob in The Long Gray Line.

May Wynn appeared with Bob in The Caine Mutiny and They Rode West.

The decline of the Star System parallels that of the Studio System. Major stars rebelled at the artistic control of the studios as well as the control of their private lives. The rise of publications like Confidential in the 1950s undermined the in loco parentis practices of the studios. (The Star System continues today, however, in that stars or celebrities draw devoted fans to films, television shows, music concerts just as in the past — despite almost daily revelations about them, some self-generated on social media, that would never have become public in earlier years.)

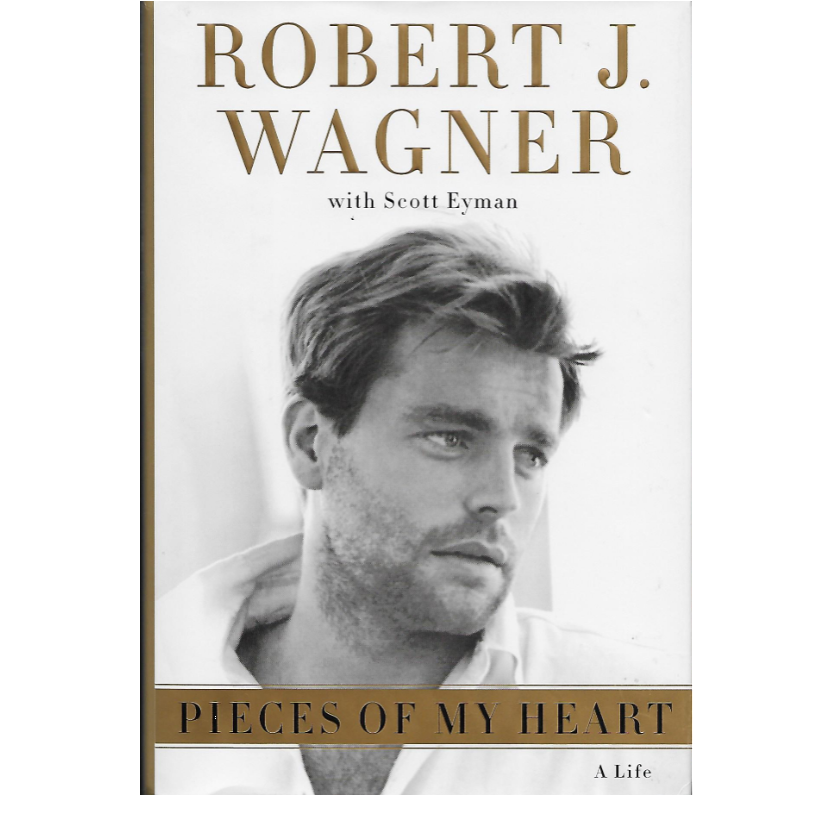

Both Robert Wagner and Tab Hunter, Star and Studio System products of Bob’s generation, published autobiographies that speak to the good and bad of those systems. Wagner and his co-author, Scott Eyman, write in Pieces of My Heart, “Fox…was very interested in me in terms of generating publicity, but it had a very limited interest in what was best for me as a human being…the studio was looking for a saleable commodity….” (p. 73) And, “…(today’s) increased independence also means that it’s everybody for himself — there’s no studio watching out for young actors, trying to build a career step by step. The only people with a vested interest in young talent are managers and agents, and there aren’t many who possess a developmental skill set….” (p. 319)

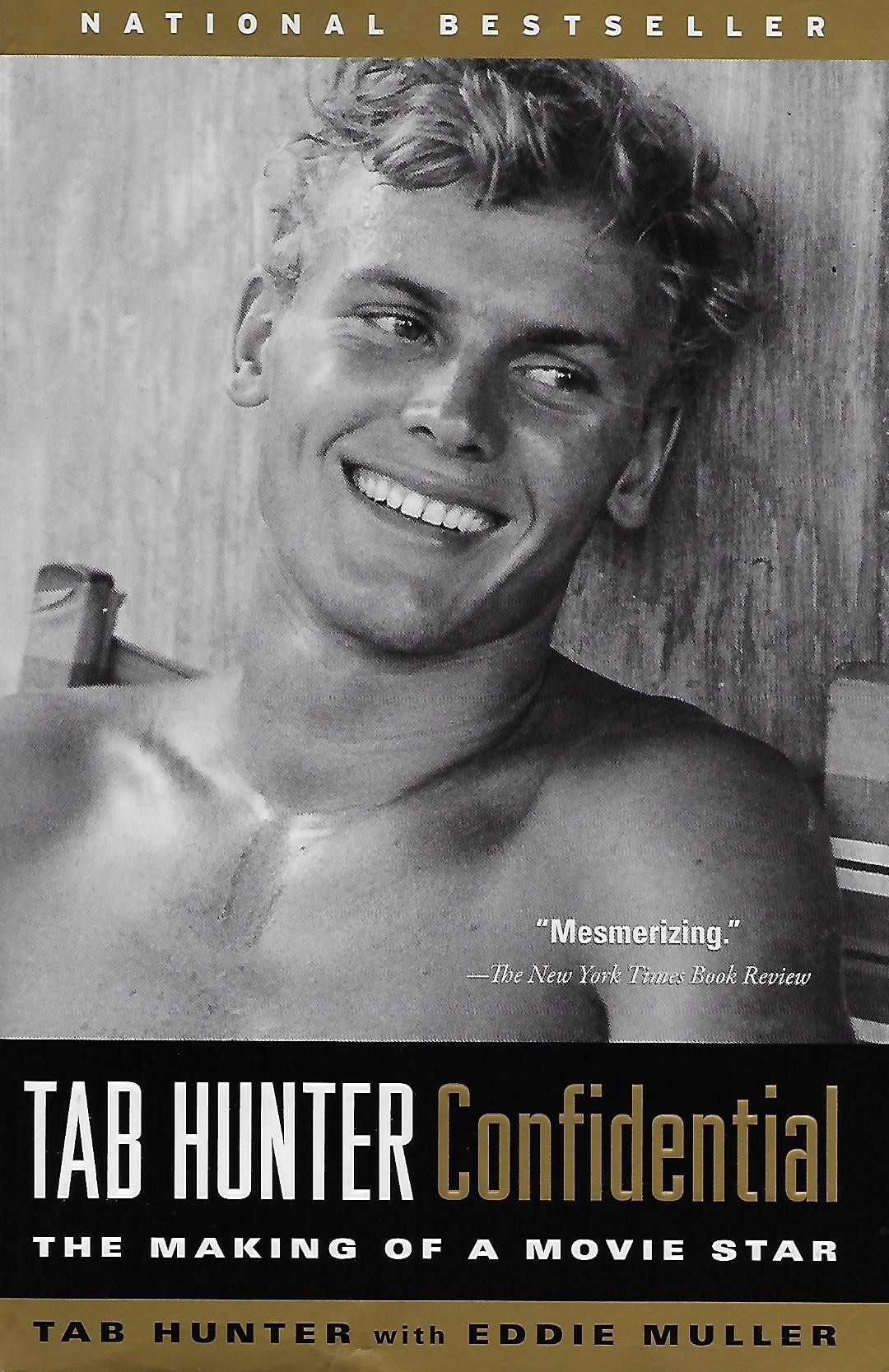

Hunter and his co-author, Eddie Muller, write in Tab Hunter Confidential: The Making of a Movie Star, “…she (Debbie Reynolds) enjoyed the security of a long-term contract at MGM. The studio had mapped out a strategy, guiding her step-by-step, coaching her singing and dancing, arranged all her publicity, managing her steady progress in a way any freelancer would have envied.” (p. 75)

Hunter’s take on these systems, unlike Wagner’s, is shaped by his early freelance status (much more difficult then than now when it is the norm) and his need to keep secret his sexual orientation. Wagner’s experiences as a contract player probably more closely resembles Bob’s. (Wagner, born on Feb. 10, 1920, just 16 days before Bob’s birth, had a more privileged life in Detroit and Bel Air than Bob, but their careers have similar arcs. Wagner worked his way through small roles to fan magazine stardom and then significant supporting and leading roles. Bob began in a significant supporting role then played leading roles in two of his four movies.)

Gallery 3: The Star and Studio Systems as experienced by Tab Hunter and Robert Wagner

Hunter

“…I’d get my first inkling of how the publicity machine worked. I hadn’t even finished making my first movie (Island of Desire), but already fans were lining up in front of the building. They’d ask for an autograph or to have a picture taken with me. Sometimes they’d sneak snapshots of me coming and going. United Artists, it seemed, was staging a big buildup in advance of the movie’s release.” (p. 58)

“From the time I got out of bed until I crawled back to my hotel room after midnight, I did interviews and grinned for the camera until my jaws ached. It was more exhausting than making the movie…The promotion thing was about wearing the happy face – all the time.” (p. 60)

“Back in Hollywood, the PR started spinning even faster. I was interviewed and photographed countless times for movie magazines. ..Most of the stories these magazines cranked out were fabricated pieces of fluff, but it seemed to be what people wanted to read, and I was told that it was a surefire way of getting “the powers that be” to take notice of up-and-coming talent.” (pp. 62-63)

“Credit, or blame, for imprinting the image of Tab Hunter in the public’s consciousness can’t go to Henry Willson (Hunter’s agent). By all rights, it goes to the fan magazines…It was these magazines that concocted my celebrity, completely out of proportion to my actual on-screen status.” (p. 67)

“…Why did so many people want to see me in these absurdly fake situations? Tab Hunter tries on a sport coat! Tab Hunter goes on a picnic! Tab Hunter water skis!”

“My popularity was spurred by magazine editors who recognized, and tapped into, a completely new readership – teenage girls. In the past, Hollywood made movies primarily for adults. Kids never really had movie stars of their own age to moon over, unless you want to count Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland as teenage sex objects…When a young girl developed a crush, hell or high water couldn’t sway her loyalty…Apparently editors, and, more important, their advertisers, discovered there was a mint to be made force-feeding desirable young celebrity bachelors to starry-eyed girls across America. It was those shrewd businessmen – not me – who were cashing in on the boy-next-door appeal of this Tab Hunter character.” (p. 69)

“I became a fixture in the Hollywood circuit, offering newspapers and magazines the perfect image of a rising star with the world by the tail. My picking and choosing from a Whitman’s Sampler of gorgeous starlets was dutifully recorded, month by month, allowing teenage girls around the world to track my love life.

“All a ruse, of course. Most of the young actresses I dated were, like me, gamely fostering the impression that they were “hot,” even if they hadn’t worked in months…Pat Crowley…Terry Moore…Having ourselves described as “an item” or “deeply involved” was a small price to pay for access to lavish parties overflowing with delicacies otherwise unavailable to actors living on saltines, sardines, and soda pop….”

“These high-life snapshots fueled the fantasies of young girls….

“There was an underlying pattern to this conspiracy of wishful thinking. Tab Hunter, and other young, handsome actors like him, were only useful as bachelors. America’s nubile class needed to believe they actually had a chance! But what was the theme of virtually every story? Marriage! In order for lustful adolescent urges to have the culture’s seal of approval, every feature story, every interview, had to conclude with the actor’s wistful admission that, beneath the glitz and glamour, all he truly craved was a simple life of wedded bliss.” (p. 74)

Hunter, Tab, and Eddie Muller, Tab Hunter Confidential The Making of a Movie Star, Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books, 2005

“…The studio system could be emotionally difficult, because I wasn’t the only hopeful juvenile leading man being groomed for a career. There were dozens at each studio, all starting out at $75 a week, all more or less good looking, all more or less types who could conceivably replace an older leading man who was already at the studio…One of the small tortures of the way the studios operated was that there were plenty of other people who were something like you. Every time you looked around, you saw someone who was a living, breathing implication that you were replaceable. And the sad fact was that you were.” (pp. 48-49)

“…They wanted to promote the image of a carefree young stud – never my style – so I had publicity dates with young actresses around town like Lori Nelson and Debra Paget. This was a relic of the days when the studio system was in its prime. The studio would arrange for two young stars-in-waiting to go out to dinner and a dance and assign a photographer to accompany them. The result would be placed in a fan magazine. It was a totally artificial story documenting a nonexistent relationship, but it served to keep the names of young talents in front of the public. As far as I was concerned, it was part of the job, and usually pleasant enough.” (p. 62)

“…Fox was very interested in me in terms of generating publicity, but it had a very limited interest in what was best for me as a human being…The studio was looking for a saleable commodity….” (p. 73)

“…The mood on the lot was different because the people who had been there in 1949 weren’t around much anymore…There was a certain esprit de corps; everybody worked together to make the film. We worked a full day on Saturday, and if a picture was supposed to be shot in thirty-five days, you better believe that it was finished on that thirty-fifth day, no more, no less. Overtime? Forget about it.” (pp. 144-145)

“..that increased independence also means that it’s everybody for himself – there’s no studio watching out for young actors, trying to build a career step by step. The only people with a vested interest in young talent are managers and agents, and there aren’t many who possess a developmental skill set….” (p.319)

Wagner, Robert J., and Scott Eyman, Pieces of My Heart A Life, New York: It Books, HarperCollins Publishers, 2008

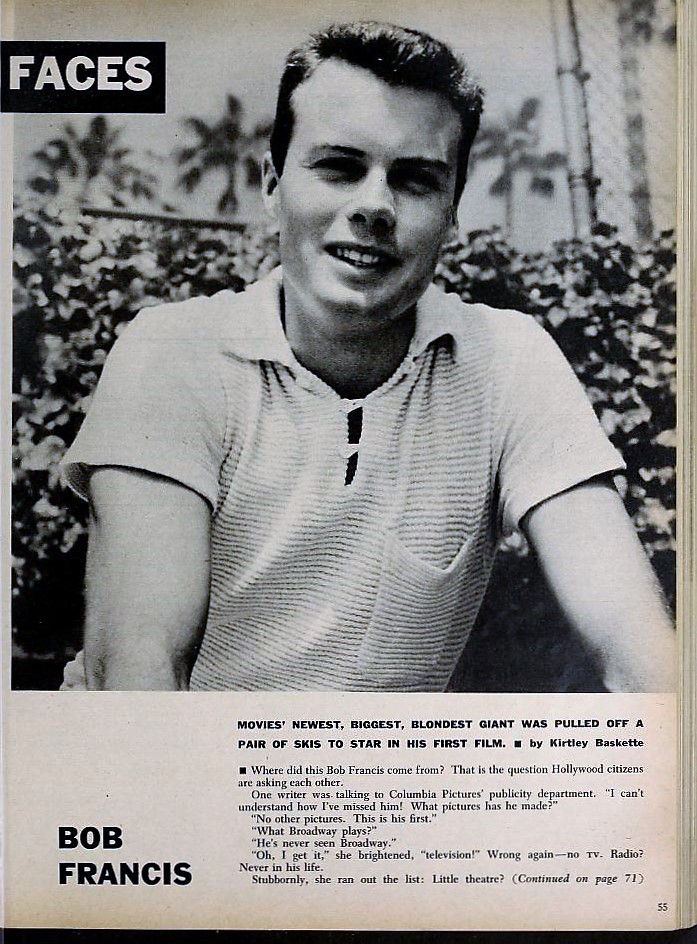

Bob’s two years in the systems provide a perfect case study of how a young player — showing enormous promise as a fan magazine favorite and a box-office attraction — would be handled, groomed, invented, launched, and secured as a “property." The intense focus of making four films in a 10-month period (June 1953-May 1954) followed by an equally intense focus on promotion and publicity, magazine photo shoots, and personal appearance tours (Spring/Summer 1954-Summer 1955) reveal a strategy designed to help Bob step into major roles in A-level films and to become a perennial favorite of fans, young and old, who would buy tickets at the box office. With some additional luck, the young man would also become a good actor and live comfortably in his own skin in the ever-fickle world of show business and movie stardom. Bob’s ace-in-the-hole was how closely his movie persona and his real life were in sync. Bob was almost, if not completely, what he seemed: an ambitious, mature young man with great joie de vivre and few, if any, secrets to hide.

The following Gallery documents Bob’s ascent from unknown to well-known (at least in the fan magazine world) and how much of his time (post-The Long Gray Line and pre-Tribute to a Bad Man) was given over to promotional and personal appearance tours, photo shoots, and his efforts to grow and improve as an actor and star personality.

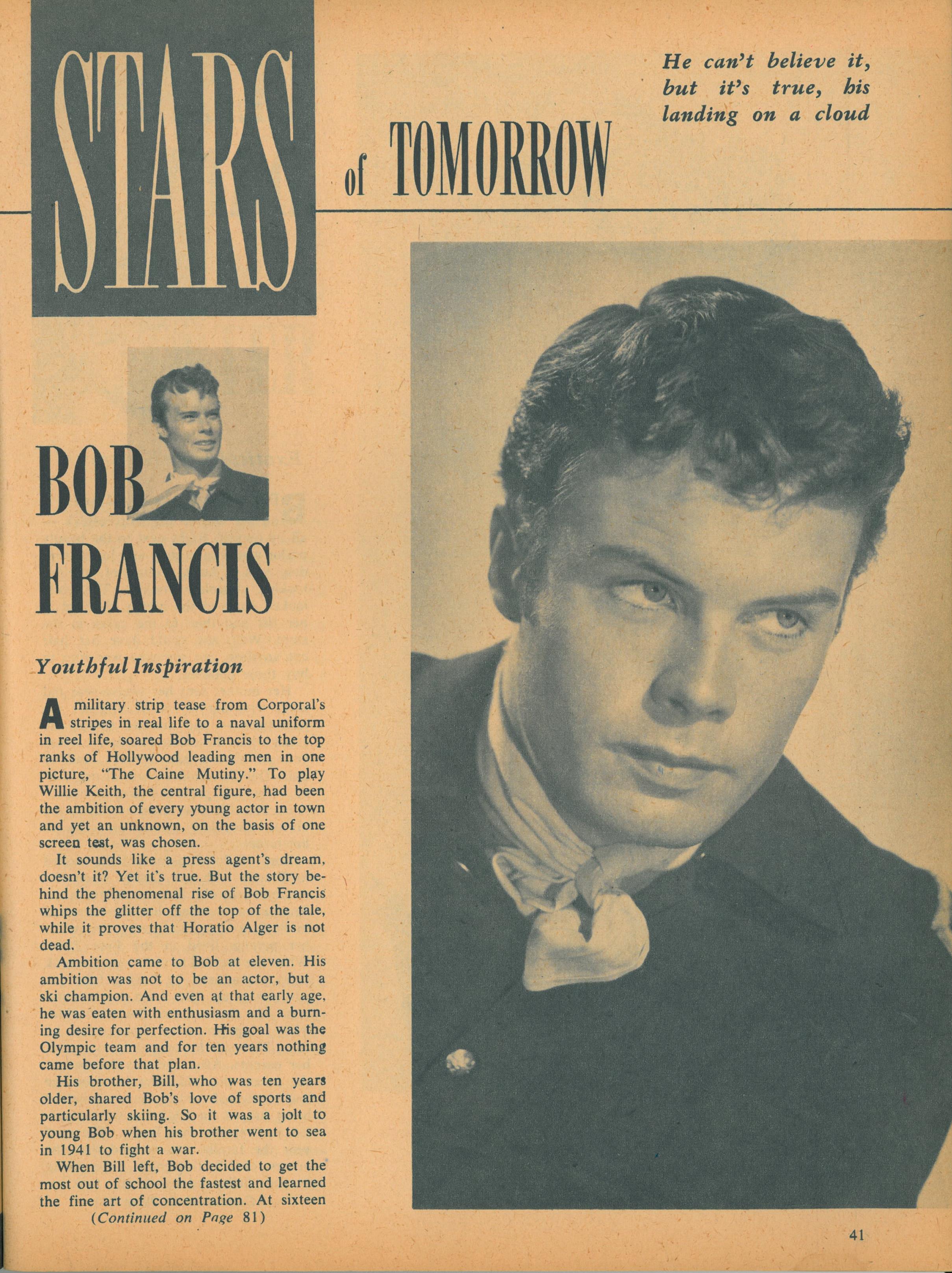

Gallery 4: Robert Francis’ Rise from Unknown to Star as documented in photographs and stories from 1953 and 1954

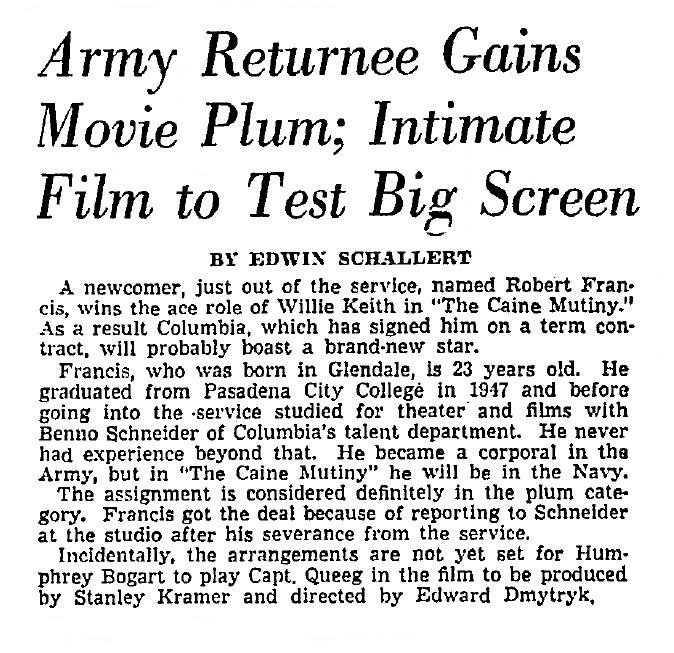

Variety?, September 1, 1949

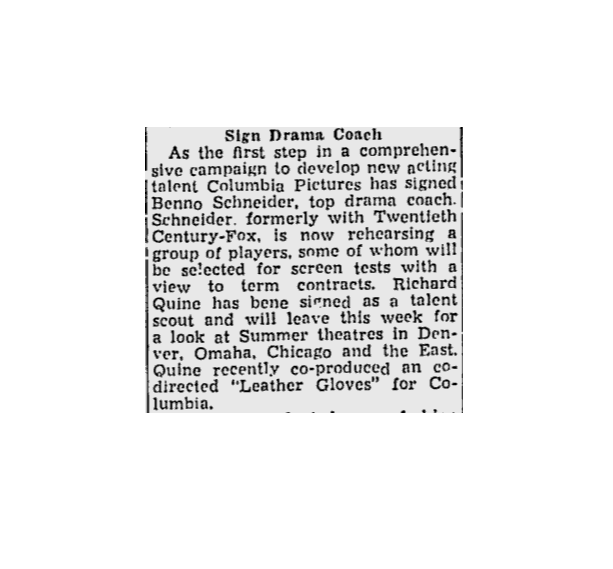

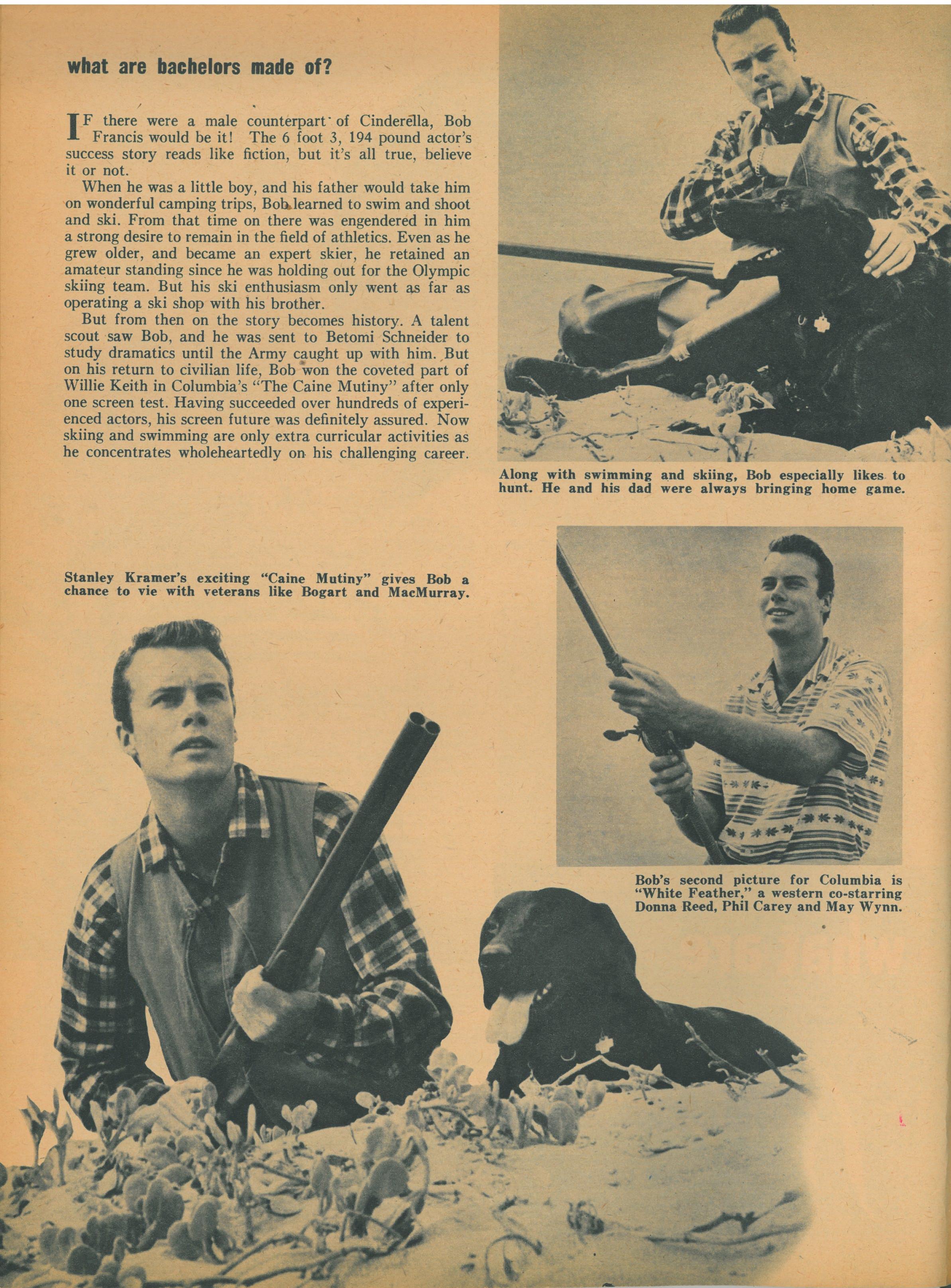

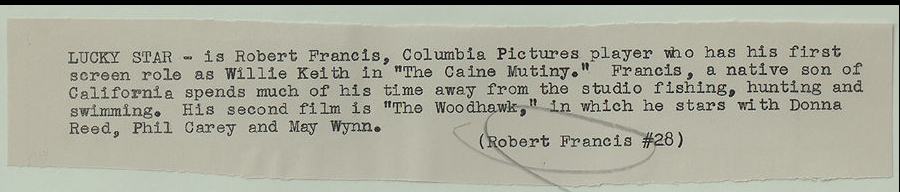

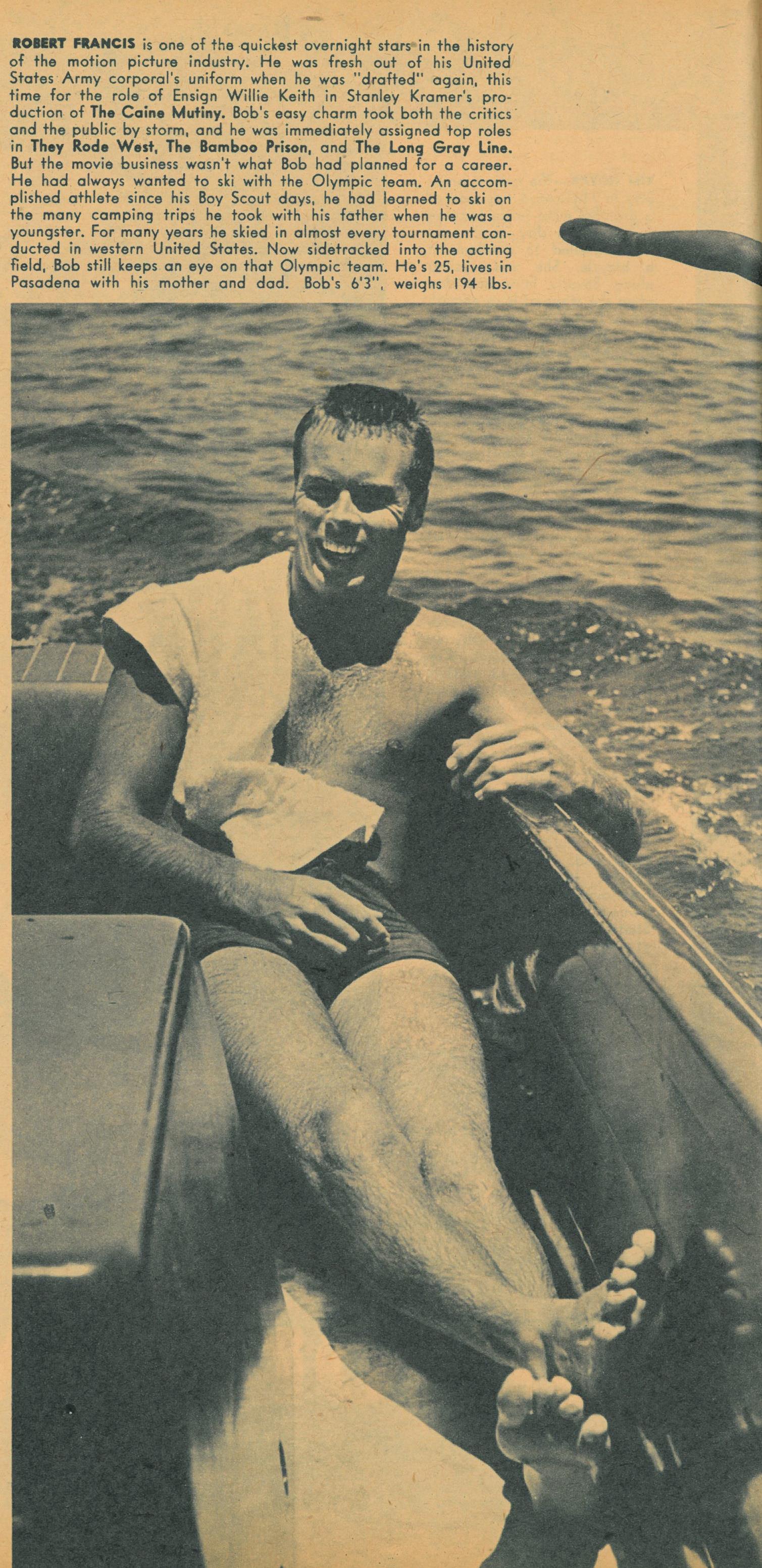

Bob was “discovered” July 4, 1949. He tested at Universal-International; from there, Sophie Rosenstein sent him to Botomi Schneider’s drama school. Her husband, Benno, in that same time period, became Columbia’s drama coach. Bob studied with Botomi for the next few years and became close to Botomi and Benno and their children. When Columbia was looking for a young actor to play Willie Keith in The Caine Mutiny, Benno recommended Bob be considered. Thus, “overnight successes” and “Cinderellas” happen.

Spring 1953

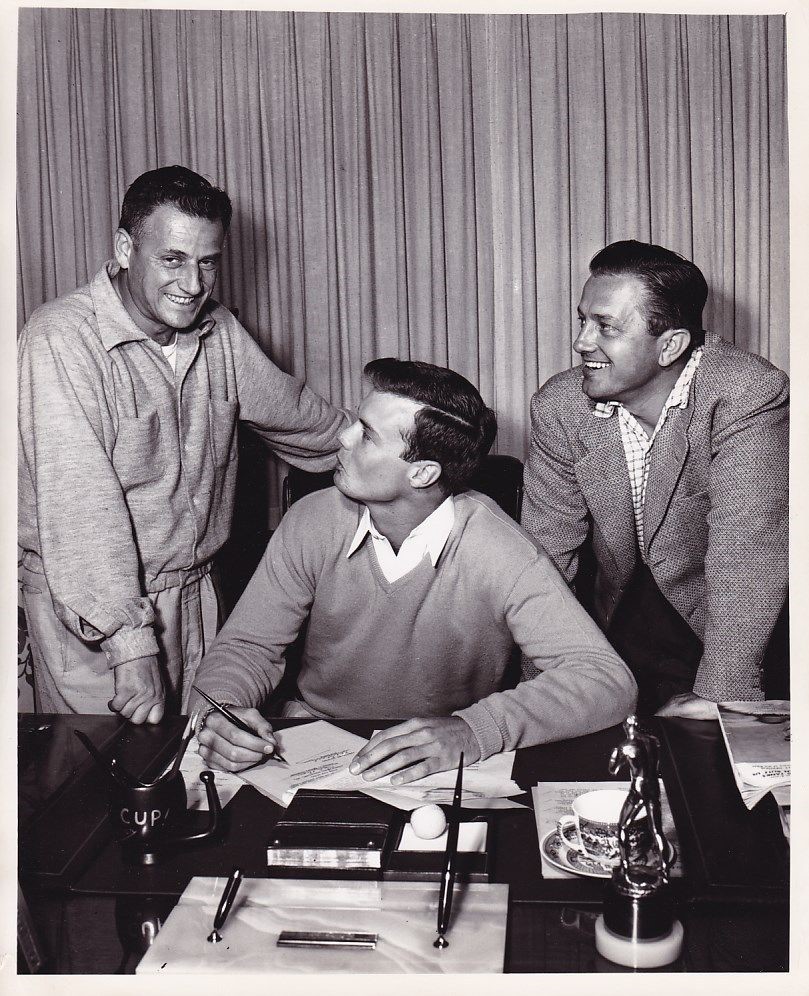

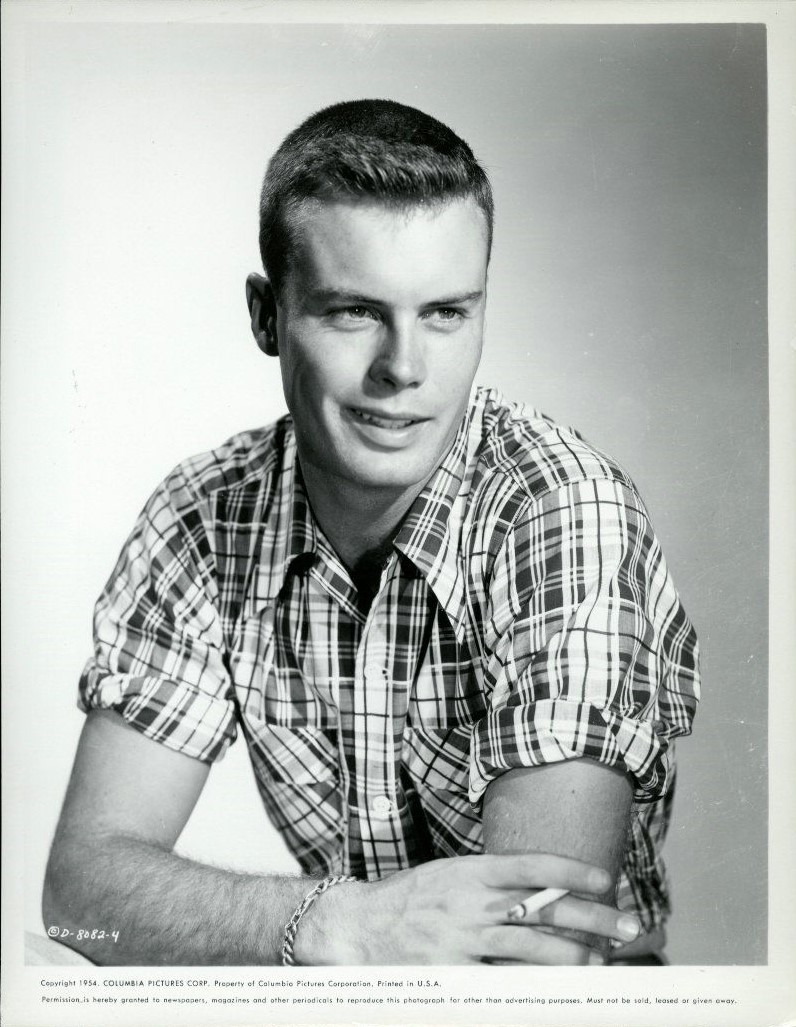

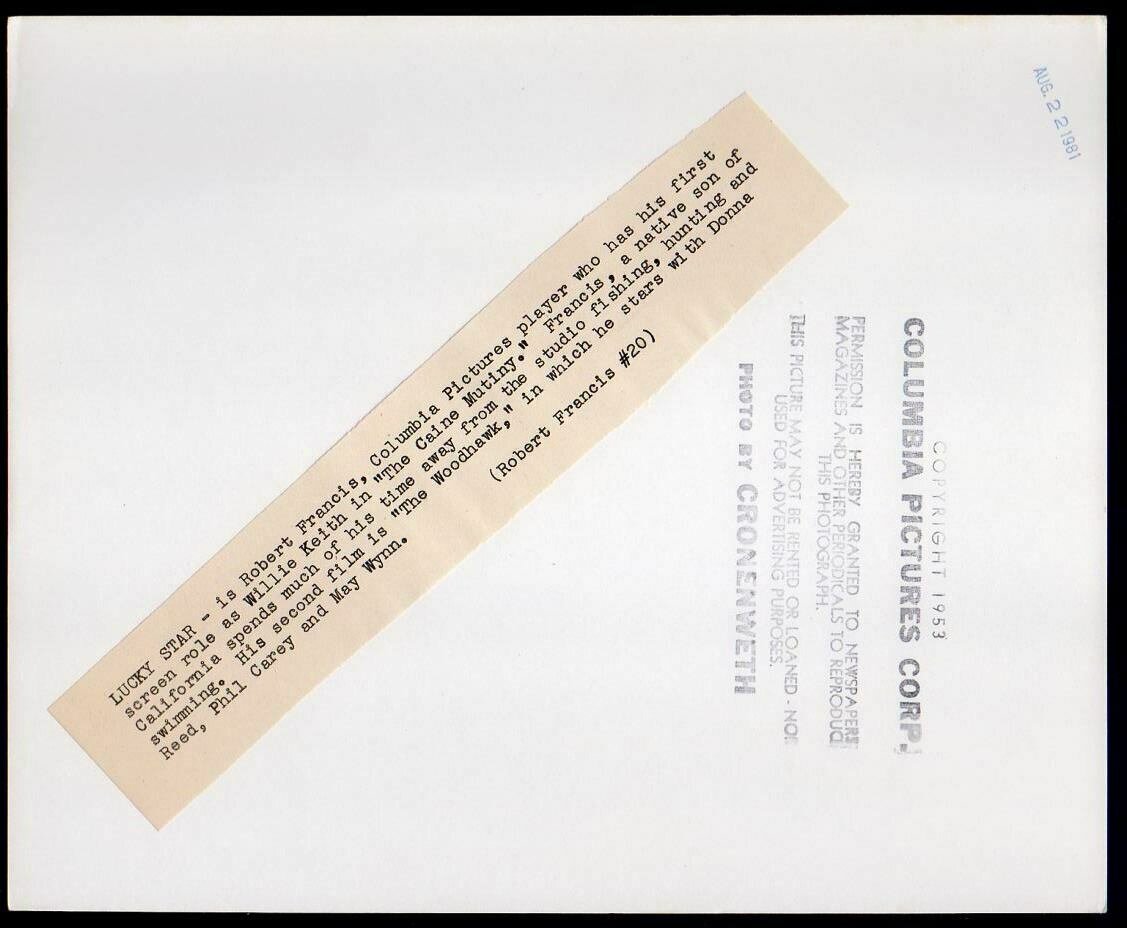

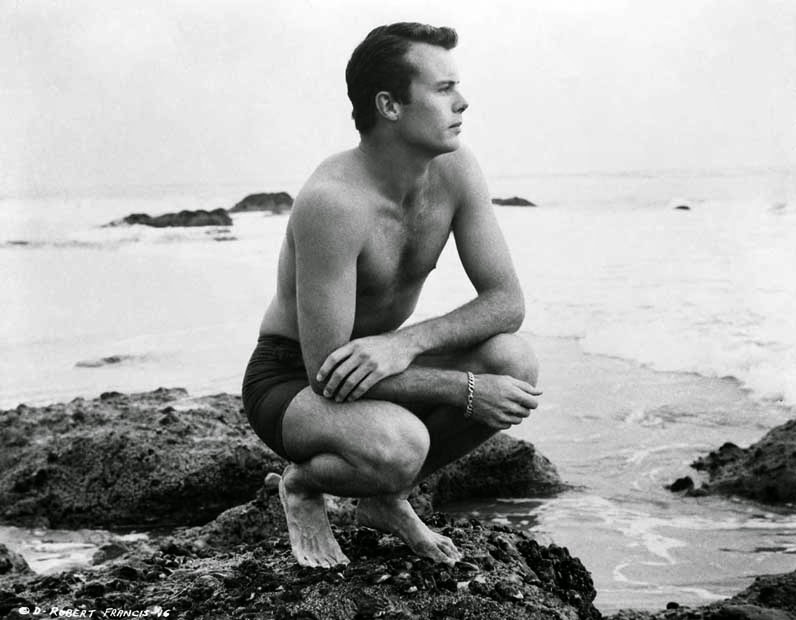

The Caine Mutiny Producer Stanley Kramer (left) and Director Edward Dymtryk flank Bob as he signs his Columbia contract. No indication of this photograph ever being published. Columbia Pictures photographer assumed. Probably made in Kramer’s office; boxer statue may have been a gift from Kirk Douglas who starred in Kramer’s Champion. A personal item, an identification bracelet on his right wrist — popular with young people in the 1950s — shows up here and in many photos made in the 1953-1954 time frame, as well as in The Caine Mutiny.

Dymtyrk was married to Jean Porter, a starlet at MGM in the 1940s. They met when MGM loaned her to RKO to replace Shirley Temple in Till the End of Time (1946). They married in May 1948. He died in 1999. She was born Dec. 8, 1922, and died Jan. 13, 2018.

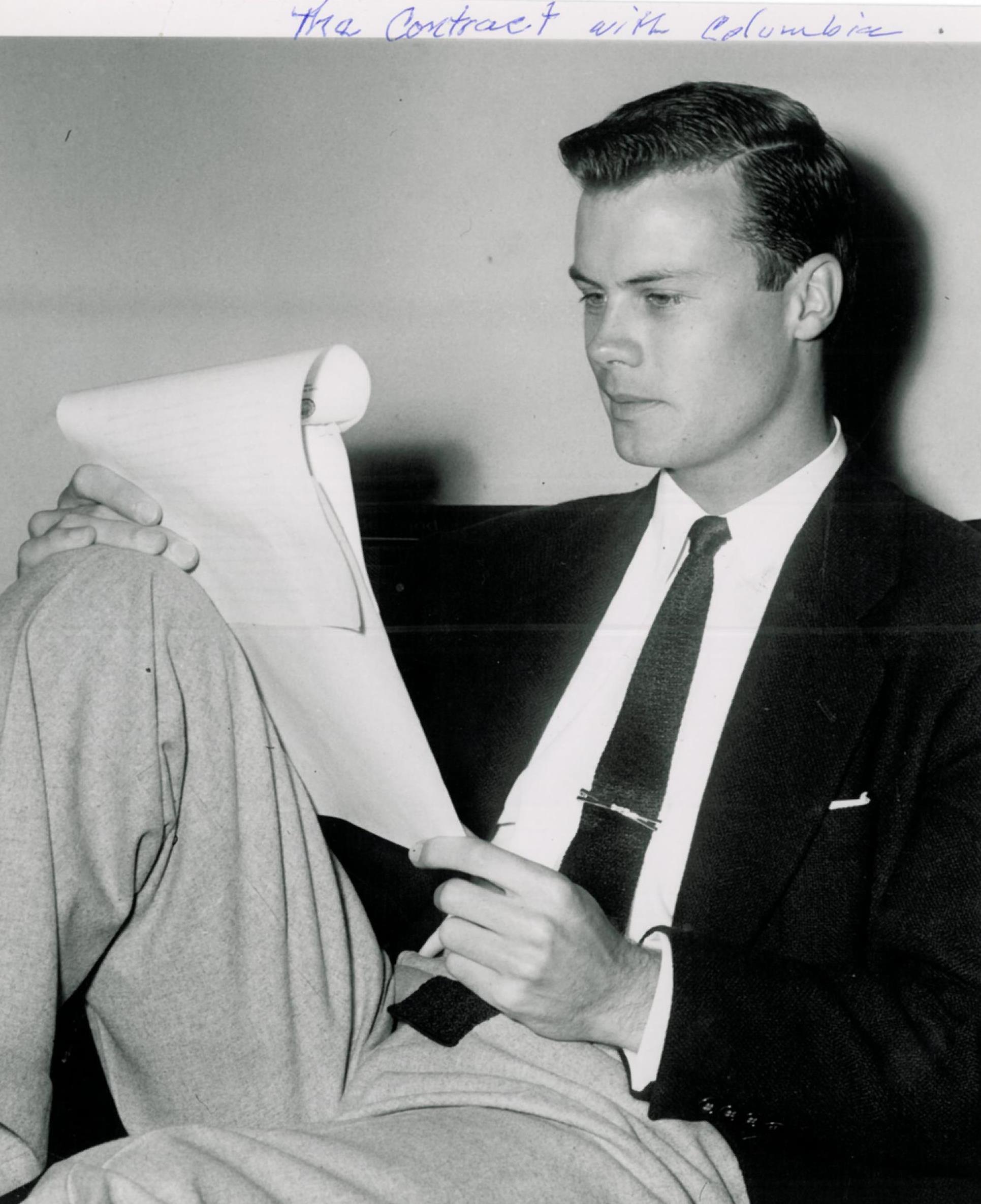

Spring 1953

Bob with his Columbia contract. Appeared in Pasadena Star-News, April 23, 1953. No caption or story available.

Bob’s first contract probably started him at $75 per week with studio options every six months and a slight salary boost when each option was picked up. Bob’s $75 per week could become $150 per week after six months…if picked up for an entire year, 40 weeks of salary were guaranteed. (Bob had a new contract after The Long Gray Line paying him double his previous salary which may have already been increased from the initial $75/week.) During those 40 weeks, the studio could schedule publicity tours, photo shoots — whatever might help an actor become “known” by movie fans — as well as drama classes, riding lessons, fencing lessons, singing lessons, etc.— whatever it felt would help the player be prepared for any role in any film.

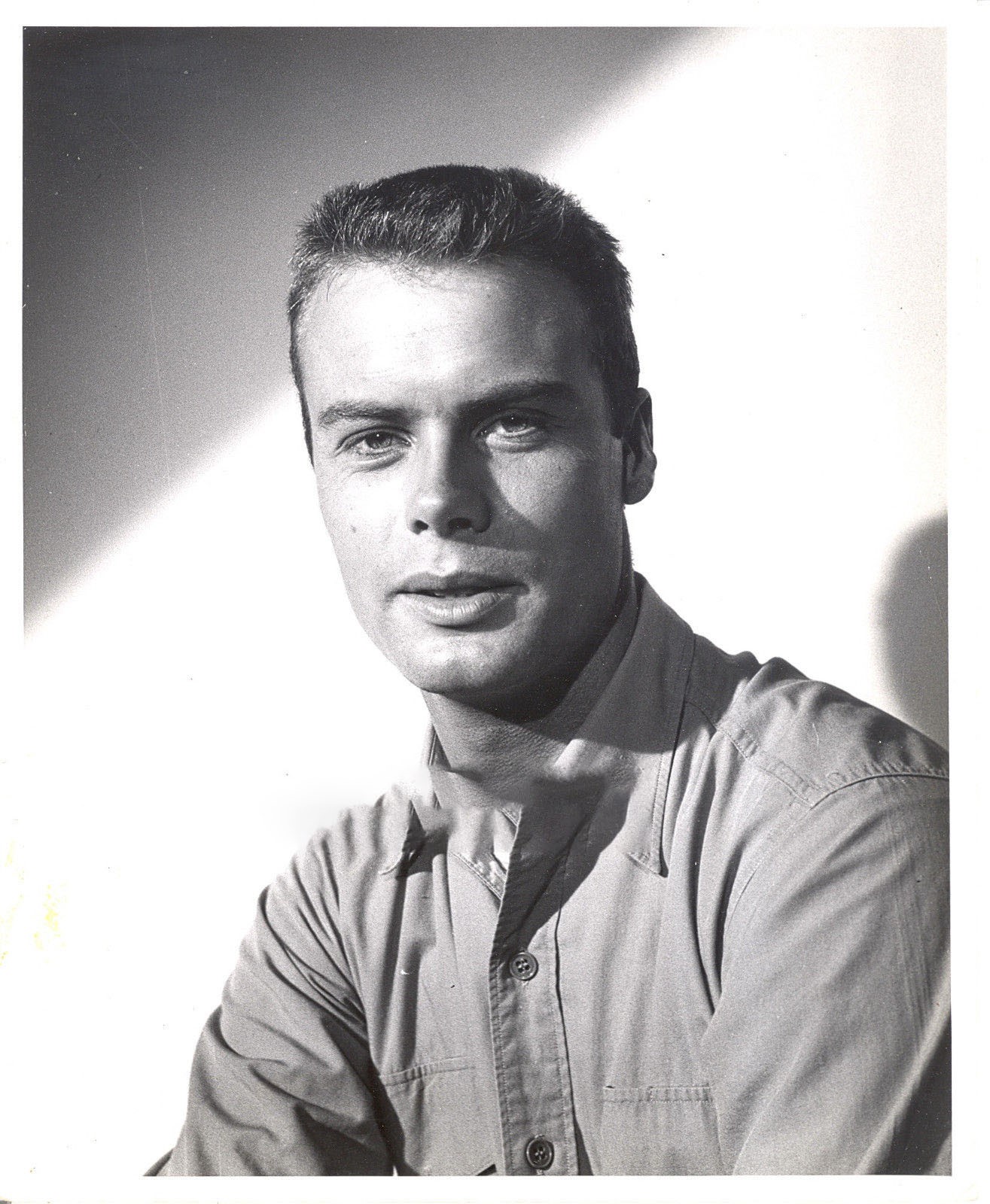

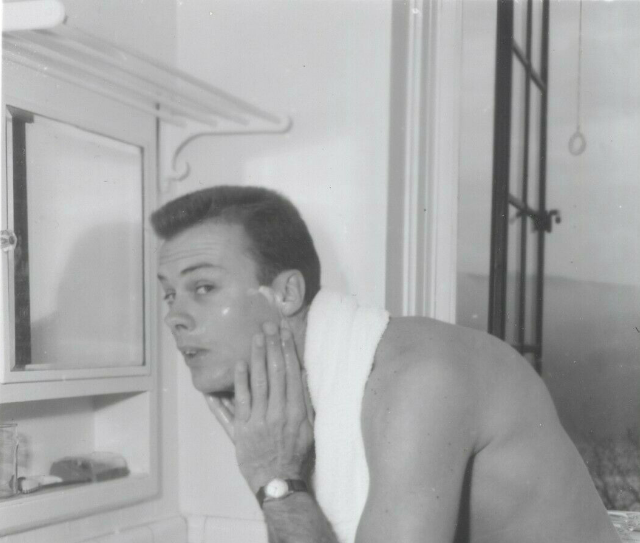

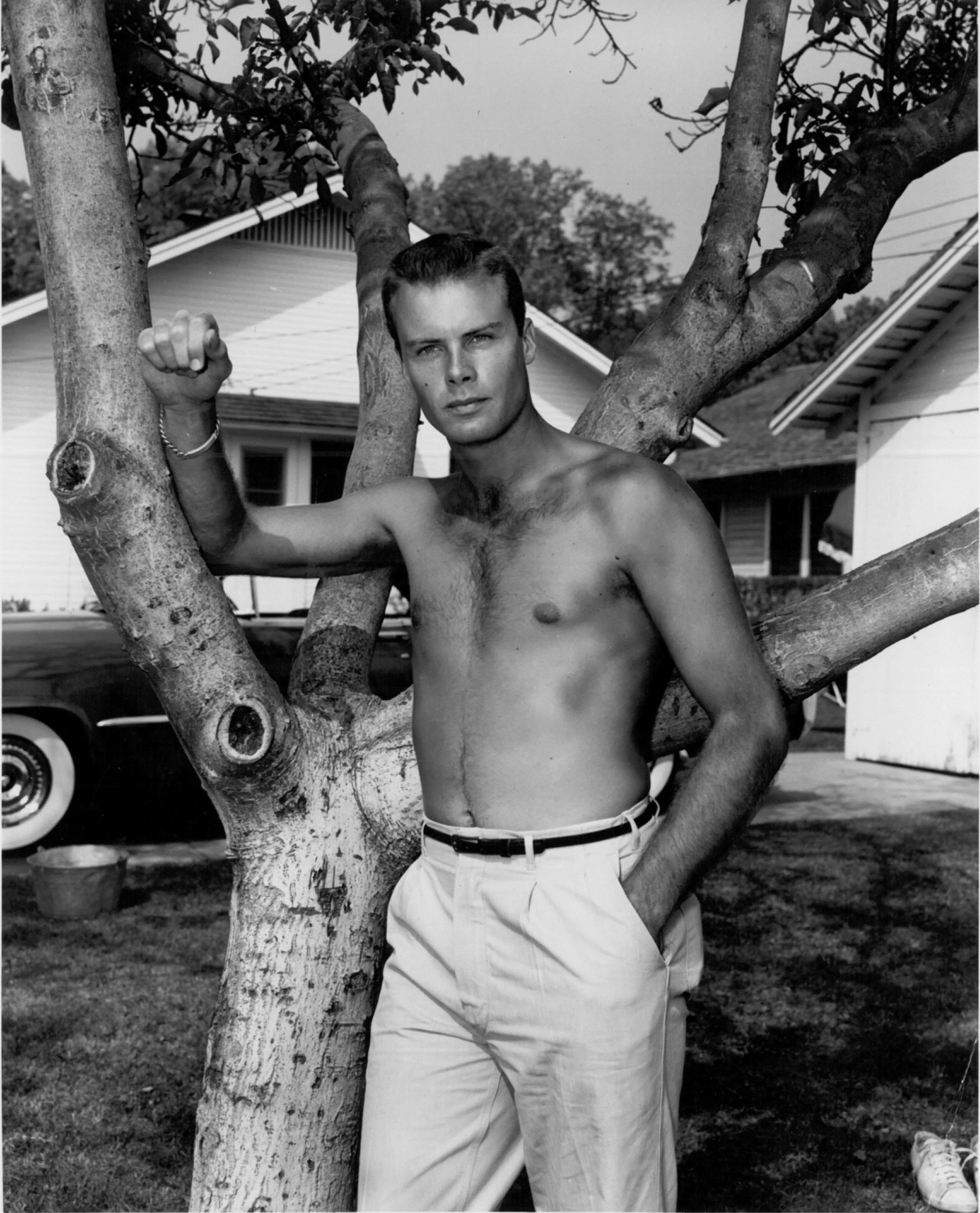

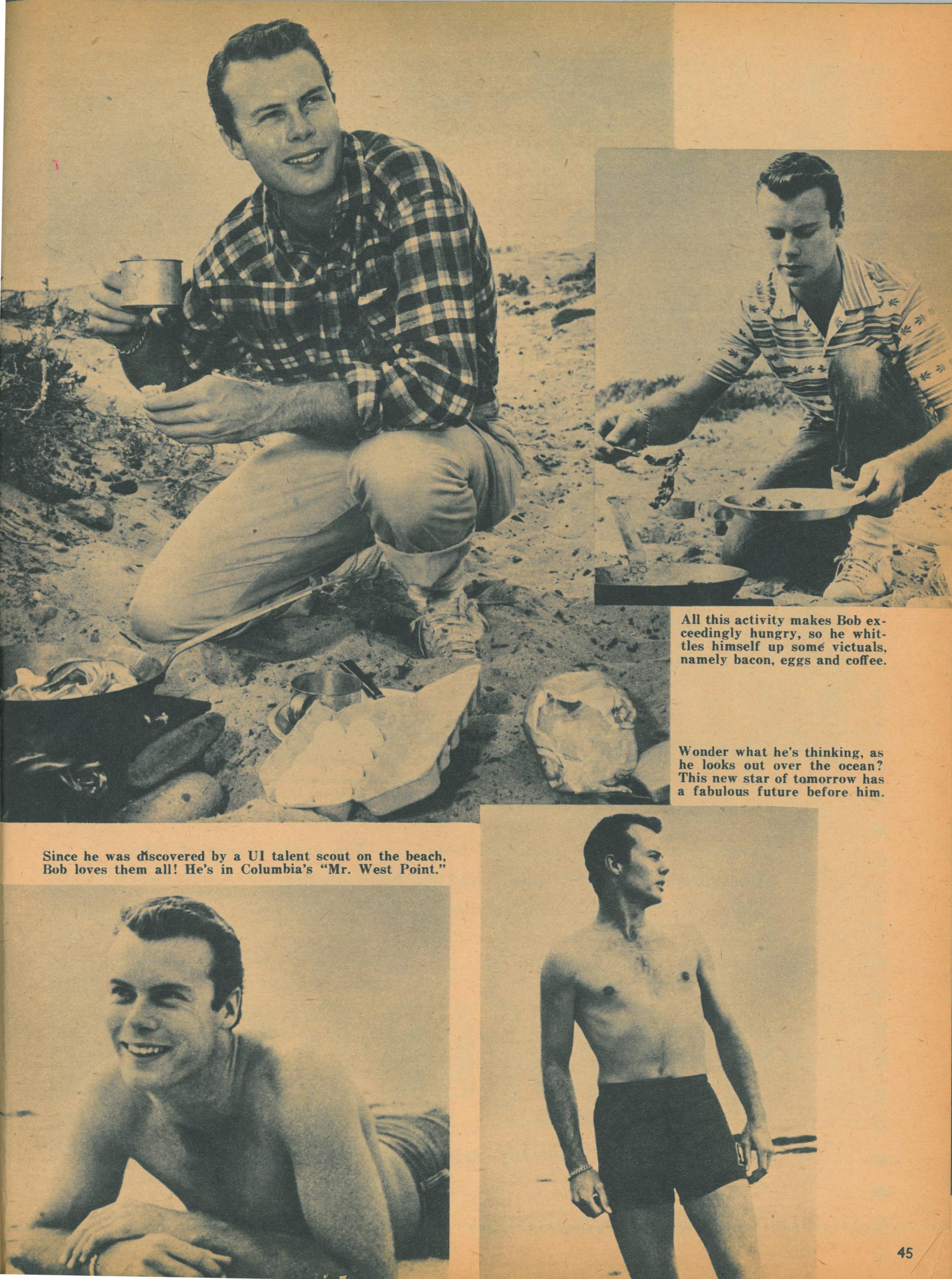

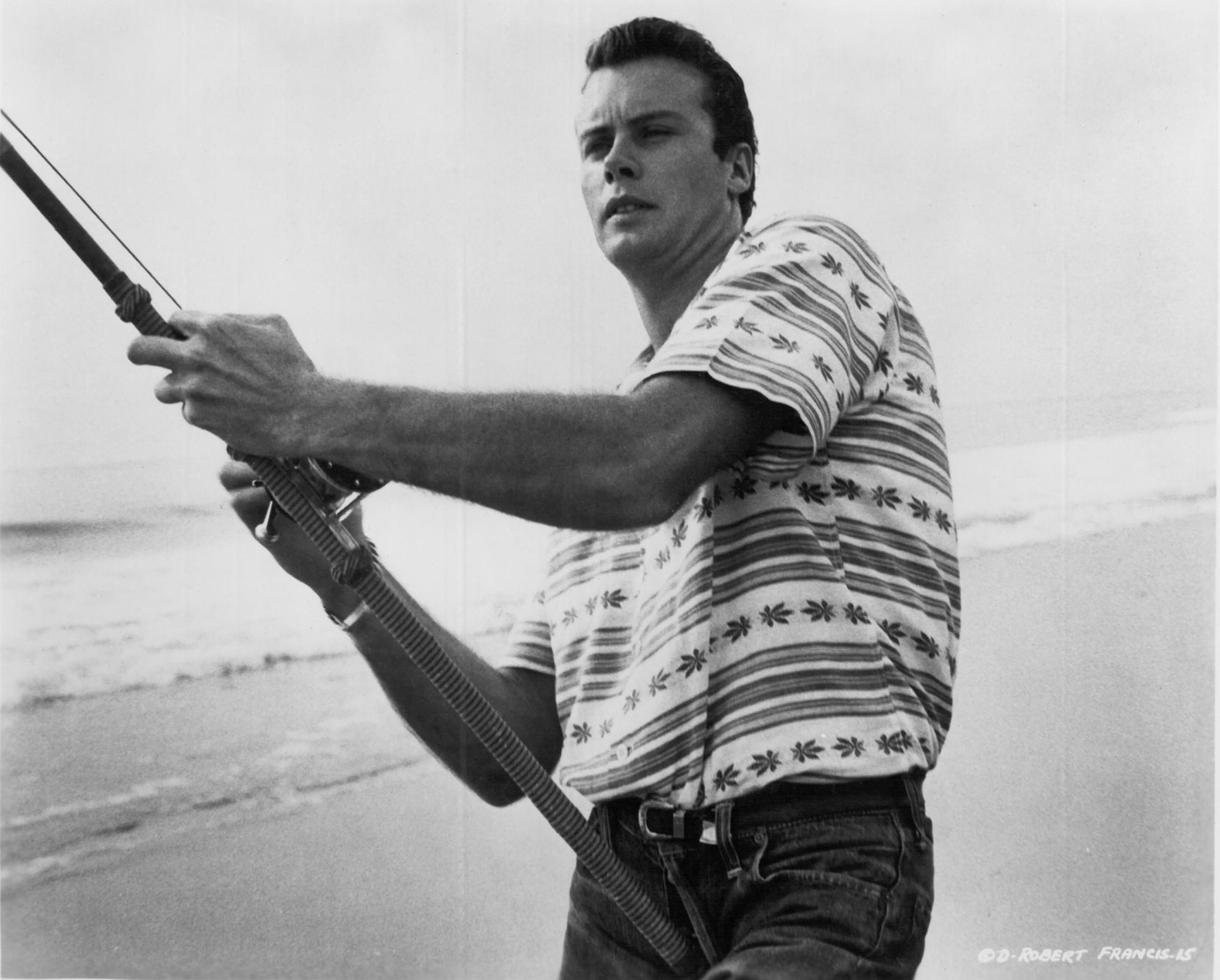

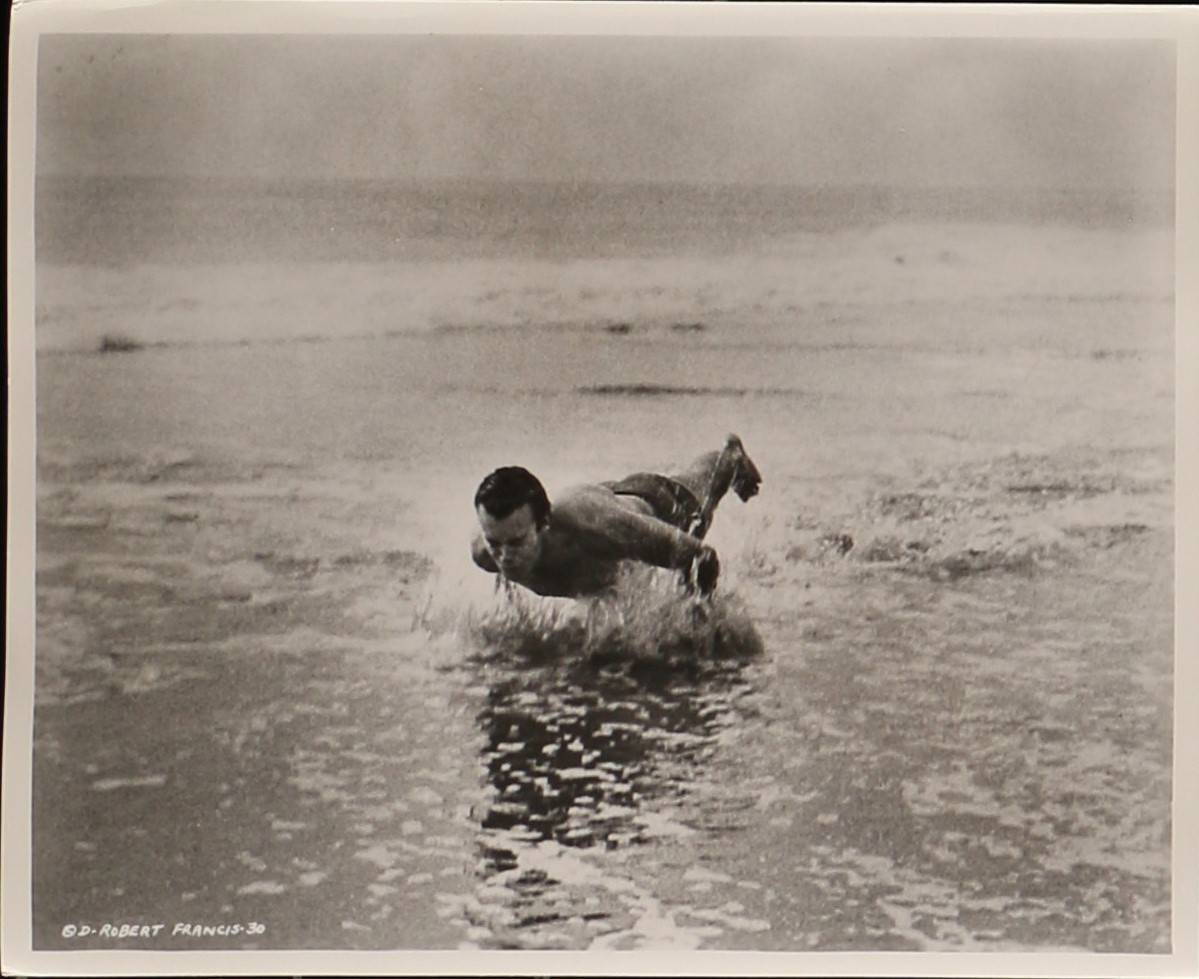

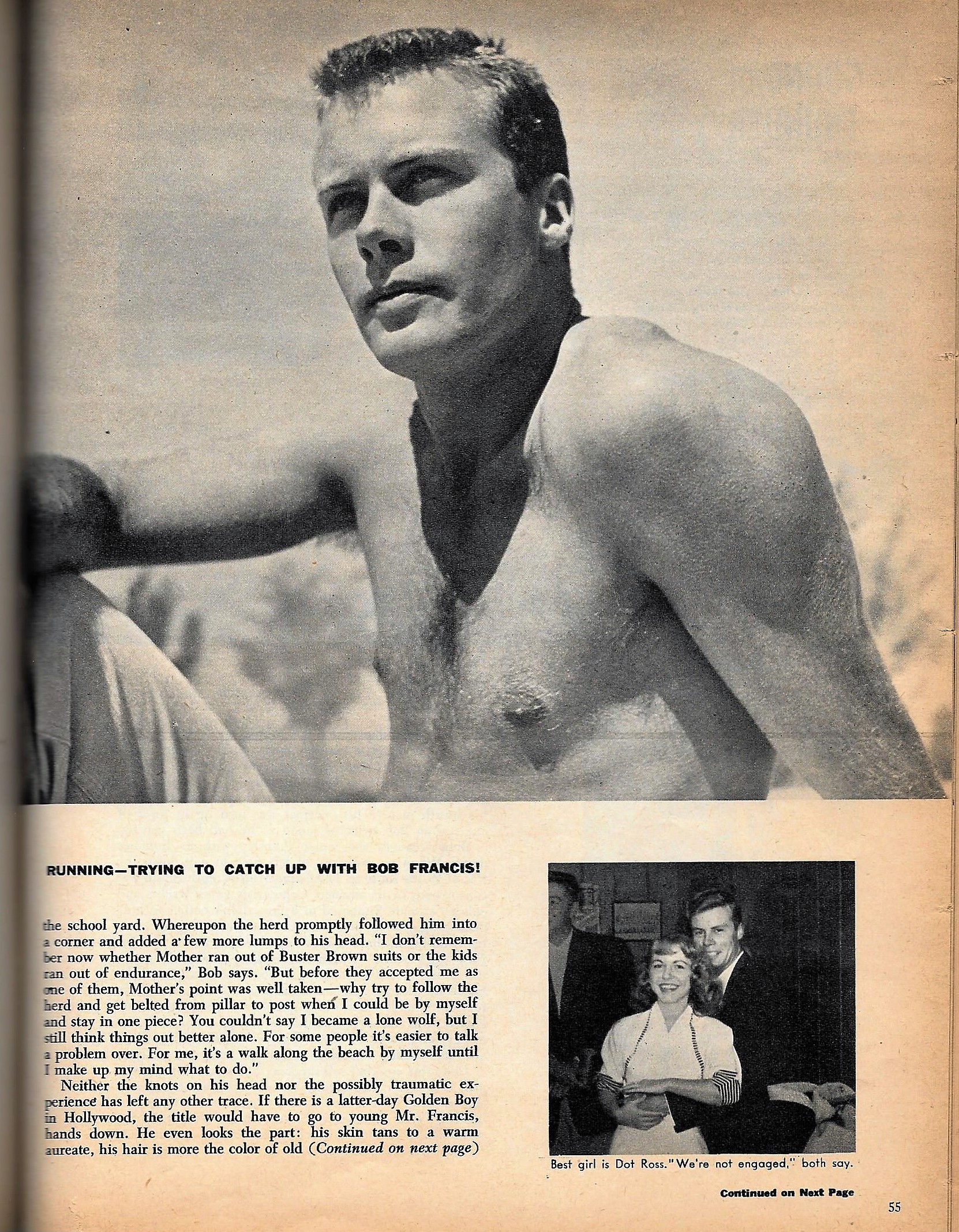

Bob’s schedule was filled with photo shoots, including a generous amount of “beefcake”/shirtless photos, drama classes, and publicity tours during the two-plus years he was under contract. In this respect, he was like most other new contract players, male and female, who were being groomed for stardom: Robert Wagner by 20th Century Fox, Tab Hunter first by United Artists and then by Warner Brothers, Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis by Universal, and scores of others whose names and faces were familiar to fan magazine readers, if not to the general public in their first months/years as a new contract player.

A distinction Bob enjoyed among most of these others was he did not work his way through a series of one-line and minor roles, then into second- and third-lead roles, then into lead roles in “B” movies, then supporting and lead roles in “A” movies. Bob began in the latter: the major supporting role in an “A” movie, The Caine Mutiny. He then played the leading male roles in two “B+” movies, They Road West and The Bamboo Prison, before playing another supporting tole in an “A” movie, The Long Gray Line. Had he lived to complete Tribute to a Bad Man with Spencer Tracy or James Cagnery, his role would have been a supporting/lead hybrid in an “A” movie — with more of the same and lead roles ahead.

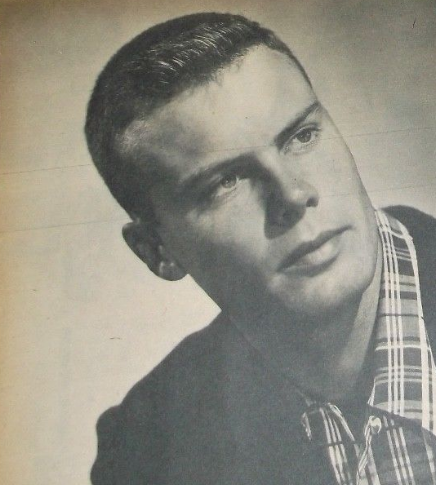

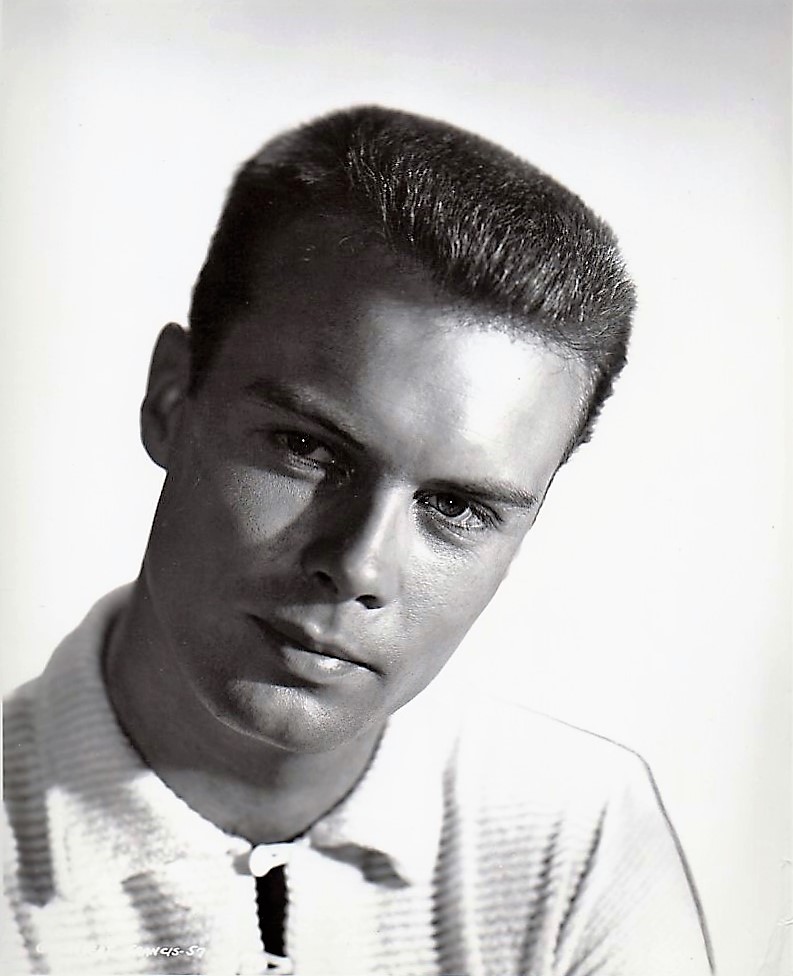

Winter/Spring 1953 (based on haircut)

Los Angeles Times, c. April 1953.

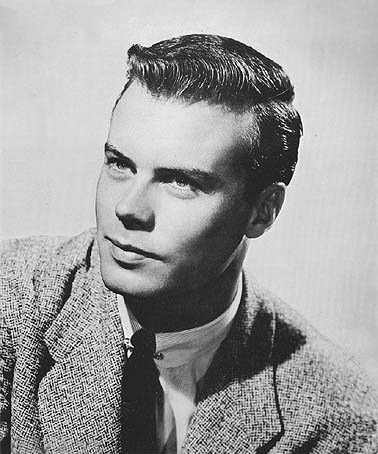

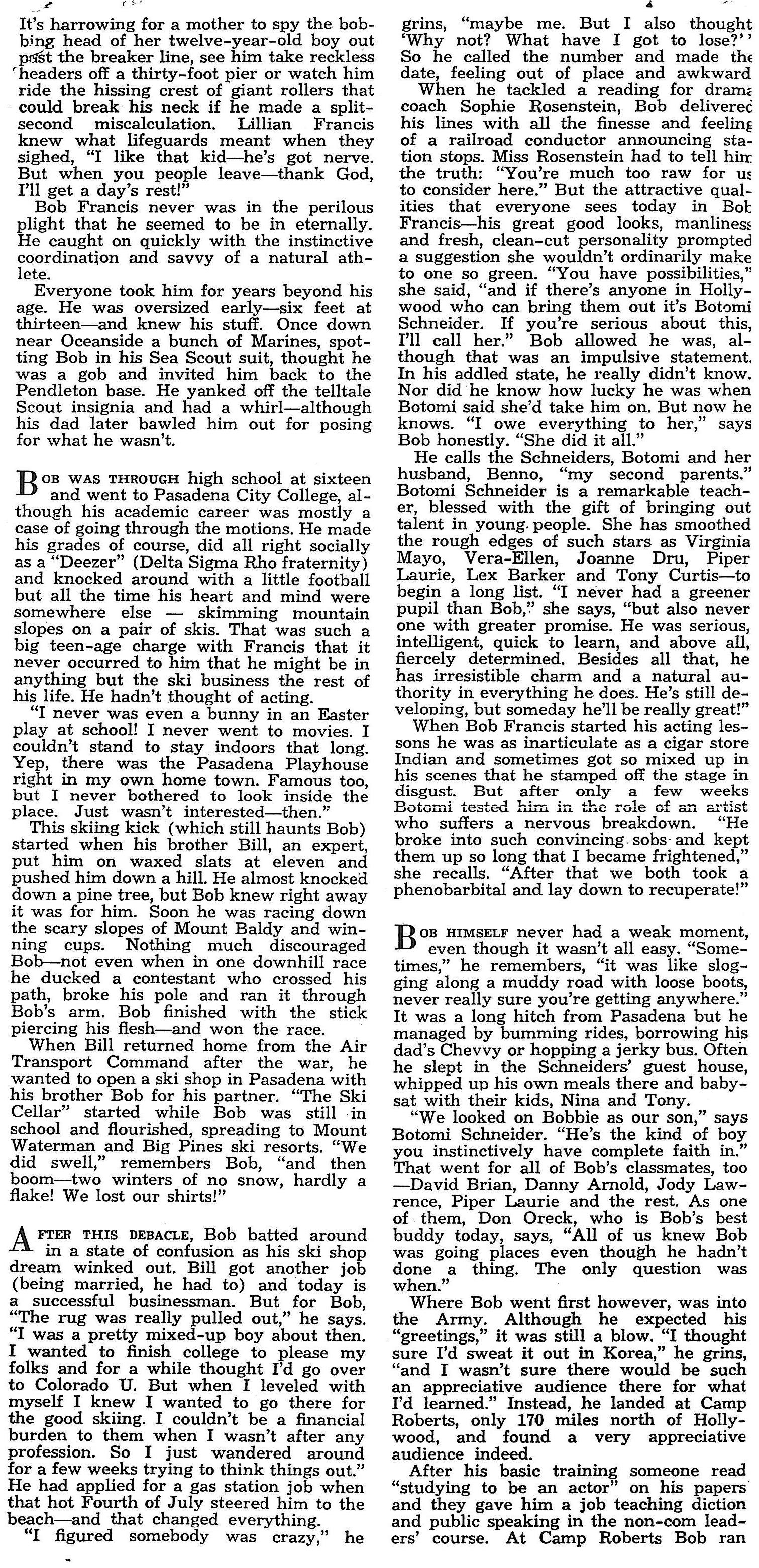

Spring 1953 Probably one of Bob’s first publicity photos. On request it was sent (usually signed or with a note and signature) to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of fans who wrote to him in 1954 and 1955. Bob’s sister, Lillian Robins, helped with some of his fan mail and, on occasion, signed his name. An example of an authentic signature is shown in the Home section. Note similar hairstyle to “contract photos.”

Spring 1953 photos

“I have always been fascinated by how celebrity is created—not by the current stable of reality personalities, whose stardom is possible without talent or reason, but rather by the classical idea of a Movie Star. I had an early realization that the people we fawn over in the movies had childhoods just like the rest of us, as I watched a few of my classmates find their way onto the big screen. But I also came to observe that much of the mystique and glamour came from the marketing machines of Hollywood, where an ordinary Kansas-born kid was transformed into something more in a photograph, through makeup, wardrobe, a striking pose, or a flattering angle of light. Over the years, I’ve pored over hundreds of photographs of Hollywood hopefuls in books that celebrate the efforts of studio photographers such as Clarence Sinclair Bull, George Hurrell, Frank Powolny, and Jack Albin. All of them had the ability to exploit the visual markers of success and produce images that turned a Norma Jeane Baker into a Marilyn Monroe.” - Aline Smithson. “Homemade Hollywood Portraits,” New Yorker, Sept. 11, 2015

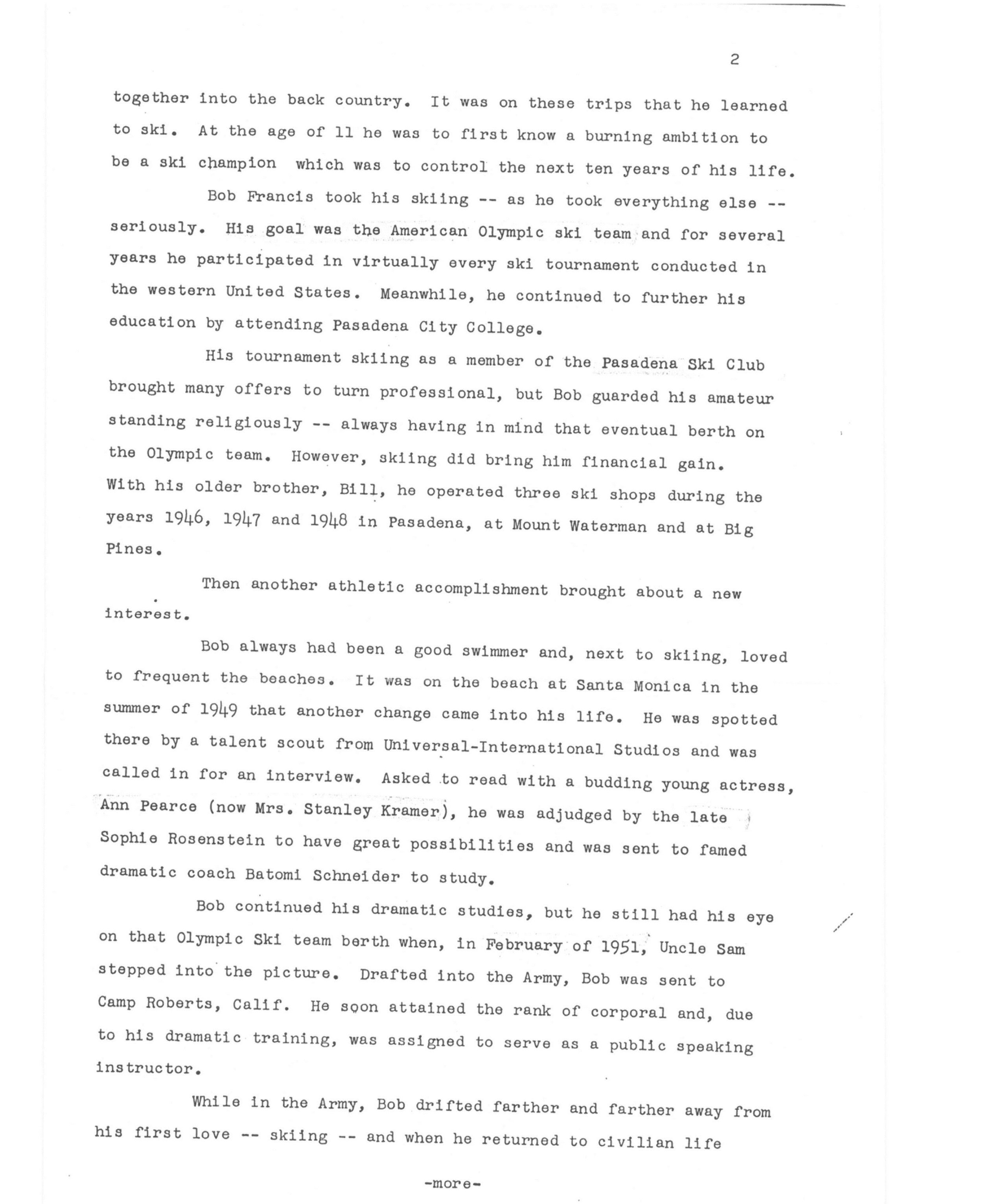

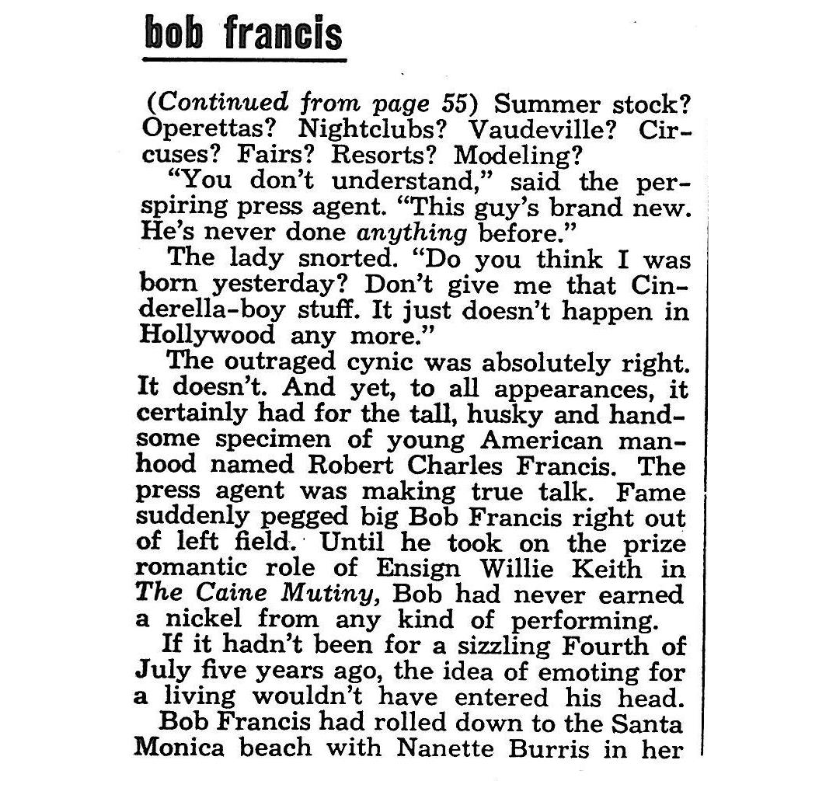

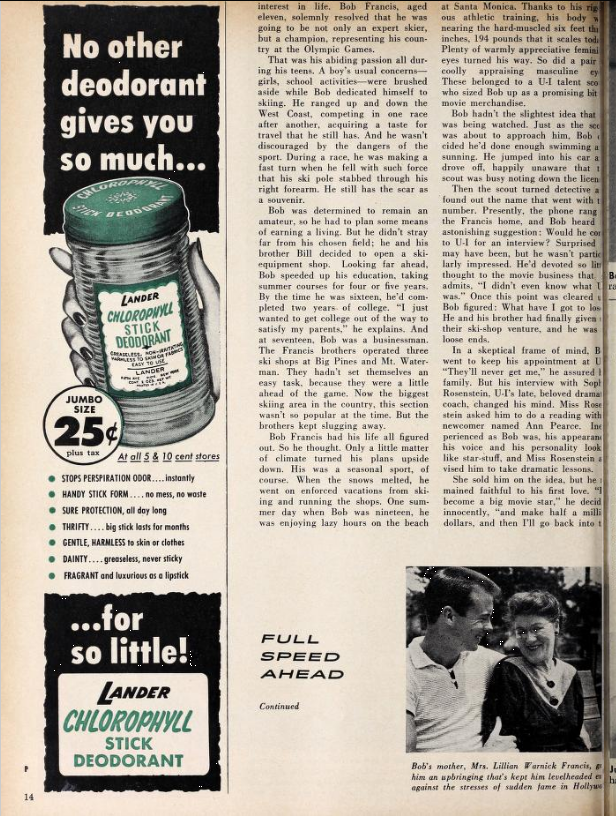

Bob’s official studio biography — this one probably from late 1953-1954 when The Bamboo Prison was still titled I Was a Prisoner in Korea — establishes the main themes of Columbia’s star-making publicity machine at work on Bob’s behalf: his All-American boy background within a warm, loving family (with whom he still lived); his passion for sports and his abilities in that area; his commitment to becoming a good actor as demonstrated by his work with dramatic coaches over several years, even when serving in the Army — preparing him for what might seem to be an “overnight success,” and his remarkable maturity for one so young. These themes would appear again and again in fan magazine stories in 1954 and 1955. Many stories used phrases and sentences straight from the biography.

The happy circumstance for all was that the biography was true. Bob lived up to the hype because it was not manufactured, not filled with “wide-eye exaggerations, casual polishings, careful erosion of inconvenient fact.” (“Astro Mad Men: NASA’s 1960s Campaign to Win America’s Heart,” The Atlantic Monthly, July 2013.)

Another happy circumstance for Bob was the shift in how Hollywood portrayed many of its stars in the post-WW II era. In earlier days some stars had personas that depicted them as not only glamorous, but exotic, rarefied, other worldly — Valentino, Garbo, even Katharine Hepburn — with daily lives filled with lunches at the Brown Derby, evenings at the Coconut Grove, horse races at Santa Anita, polo and pool parties on Sundays, and secluded mansions set among palm trees and bougainvillea. To be sure stars like Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney were promoted as wholesome, all-American kids and as boys-and-girls-next-door given just as much as their peers in Kansas and Carvel to worshiping the cinematic gods and goddesses. Garland’s “Please, Mr. Gable” version of “You Made Me Love You” is a good example of the blending of Hollywood magic and the dreams of millions of girls and young women. Although there would be other gods and goddesses in post-WW II Hollywood — Elizabeth Taylor, Ava Gardner, Grace Kelly, Marilyn Monroe — fan magazine coverage favored a “the stars are just like you and me” approach. Thus, stars were often captured in full 1950s mode with barbecue grills and photos made in their very-nice-but -really-just-average-homes with spouses and children or “dates” engaged in family-oriented and every day, typically All-American activities — shopping for clothes, bowling, golfing, camping, buying homes, having babies. In many ways this shift also reflected the post-war desire for peace and home and stability and security and achieving the American Dream. Savvy consumerism, establishing nuclear families, domesticity — these were important to many Americans and they liked having famous movie stars with similar interests and values. Bob’s life experiences and the key aspects of his publicity also reflected this side of life in the 1950s. He was certainly someone many young people could relate to, and certainly someone to introduce to parents and friends.

Although parents and siblings sometimes figured into a star’s publicity work, Bob had a significant number of photo stories in which his parents appeared; most were shot in his and their Pasadena, Calif., home. That Pasadena was close to Hollywood and Bob was still living at home allowed this “up close and personal” approach more than for most other young stars. An obvious contrast was James Dean, the brilliant young actor killed in a car accident Sept. 30, 1955, whose childhood and young adulthood were filled with traumatic childhood experiences (his mother’s death, his father’s remarriage, his being left with elderly relatives, a sense of abandonment, probable sexual abuse). Rebellion, anger, hostility, rudeness — these were often the theme of stories about Dean in late 1954 and 1955. Far from Bob Francis and his supportive family in Pasadena.

(Dean’s life experiences and his publicity — much of which he participated in unwillingly — reflected the other side of post-WW II American life. “The 1950s is often viewed as a period of conformity, when both men and women observed strict gender roles and complied with society’s expectations. After the devastation of the Great Depression and World War II, many Americans sought to build a peaceful and prosperous society. However, even though certain gender roles and norms were socially enforced, the 1950s was not as conformist as is sometimes portrayed, and discontent with the status quo bubbled just beneath the surface of the placid peacetime society. Although women were expected to identify primarily as wives and mothers and to eschew work outside of the home, women continued to make up a significant proportion of the postwar labor force. Moreover, the 1950s witnessed significant changes in patterns of sexual behavior, which would ultimately lead to the ‘sexual revolution’ of the 1960s.” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/1950s-america/a/women-in-the-1950s)

According to Bob’s Columbia Studios biography, he was Scottish which is largely true on his father’s side. In addition, he had ancestors from England and Ireland/Northern Ireland, all in the United Kingdom. Plus a few people from Germany, France, The Netherlands, and Switzerland. All of these people came to America in the Colonial Era before this was a country as far back as the 1600s. These ancestors included many farmers, a planter and tanner, a few large landowners, a judge, and a justice of the peace. John Silver, Bob’s Third Great Grandfather, was a blacksmith and wagon maker who also owned a tavern. He was a deacon in the local Baptist Church as was Bob’s father, Jim, in Pasadena, Calif., many years later.

During the Colonial Era several distant ancestors were in the Revolutionary War. One such person was Bob’s Fourth Great Grandfather William A. Norton (1716-1779), a captain in the British Navy, who signed the Oath of Allegiance to America on June 5, 1778. He and five of his sons fought in the Revolutionary War.

Some of Bob’s ancestors were Quakers including his Sixth Great Grandmother Abigail Fayle Garnet (1702-1780) who married her husband, Samuel Fayle, in Ireland. Then, they came to the colonies. Abigail was disowned or expelled from the Church for continual use of strong liquor, drunkenness, and scandalous behavior in 1722. Citation: Abigail Fayle Garnet - Ireland, Society of Friends (Quaker) disownments, image, FindMyPast, accessed Oct. 12, 2019. Disowned for continual use of strong liquour 16d 2m (April) 1722; citing Dublin disownments. 1662-1756, Religious Society of Friends in Ireland Archives.

Virginia-native Lewis Francis, Bob’s Second Great Grandfather, moved with his wife, Elvira, and a few sons to Kentucky where he owned and operated a steamboat on the Ohio River. He was killed by an explosion on the boat on June 14, 1839, at age 37. Another relative died after falling through the ice in a river back east.

A nephew of Lewis and Bob’s Second Great Grandmother Elvira Norton Francis was killed in the Civil War during the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, at Manassas, Va.

Famous Ancestors

The Vanderbilts

Bob’s Sixth Great Grandparents, Nehemiah (1700-1776) and Lydia Lum Hand (1701-1776), lived in N.J. and had many children. One of them was Private Hezekiah Hand, Bob’s Fifth Great Grandfather. Another was Captain Samuel Hand (1728-1817) who had ownership in a shipping line when the Revolutionary War broke out.

Samuel Hand’s daughter, Phoebe Hand (1767-1854), married Cornelius Vanderbilt (1764-1832). Their son was the wealthy Cornelius Vanderbilt II (1794-1877) aka “The Commodore.” Cornelius II and Phoebe are both interred at the Vanderbilt Mausoleum in N.Y. This makes Bob and his siblings distant cousins of the Vanderbilt Family. Citation: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/48703877/Phebe-Vanderbilt and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornelius_Vanderbilt

See photo of Phoebe Hand Vanderbilt (below)

Richard Nixon

Bob’s Seventh Great Grandparents on his Grandmother Mary Silver’s side in Colonial America were Mordecai (1660-1717) and Mary Parsons Price (1661-1718), both born in Maryland. Mordecai’s Great Grandfather came to Jamestown, Va., in 1610 from Wales on the Ark or Dove merchant ships. Mary’s ancestors came from England.

Mordecai Price is also the Sixth Great Grandfather, through a different son, of the 37th President of the United States Richard Milhous Nixon (1913-1994) on his mother Hannah Milhous’s side. This means Bob was the Seventh Cousin Once Removed of Richard Nixon. Citation: www.NixonLibrary.gov

The Duchess of Windsor/David B. Merryman

Bob has a distant “connection” by marriage to David Buchanan Merryman (1856-1900), the uncle of Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor (1896-1986). In 1894 David Merryman married Bessie Love Montague (1864-1964), the sister of Wallis’s mother, Alice Montague. The Merrymans were a very old Baltimore family going back hundreds of years.

In the time period 1934-1936, “Aunt Bessie” was the well-known chaperone of her niece, Wallis, and Edward, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, during their travels and romance and the abdication crisis in England.

One of David Merryman’s ancestors, Rebecca Merryman, married a different son of the same Mordecai Price listed above who was related to Bob and President Nixon. Therefore, the relationship to the Duchess of Windsor is only by marriage. Citation: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/18332743/david-buchanan-merryman

Aunt Bessie lived the good life up until her death at age 100. The New York Times published a complete account of her 100th birthday party given by a relative in Huntly, Va. Citation: www.nyt.com

The Biography section of this website and the Sidebars section have extensive information about Bob’s ancestry.

Phoebe Hand Vanderbilt, one of Bob’s famous distant relatives

Bob’s official Columbia Pictures biography. It references all of his movies; therefore, c. 1954.

Note the earlier connection via the not-yet Mrs. Stanley Kramer (Ann Pearce). They were married 1950-1964. In 1966 Kramer married Karen Sharpe who may be best remembered in a supporting role in The High and The Mighty (1954). Bob’s playing of the Hammond organ has not been documented elsewhere or by his siblings. He may have studied piano when a youngster.

In summer, fall, and winter of 1953, Bob continued his drama classes and took advantage of other classes provided to contract players — and began appearing on the Hollywood social circuit, posing for photo stories, “dating” attractive young actresses, etc., all in front of the release of The Caine Mutiny in July 1954.

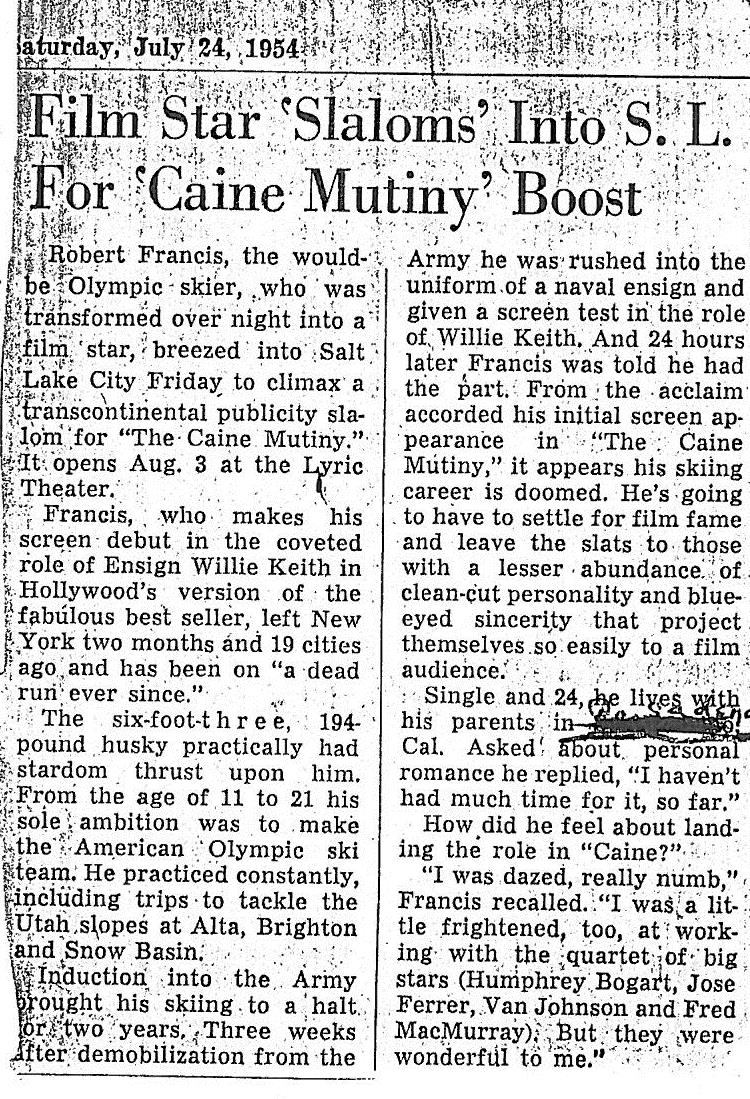

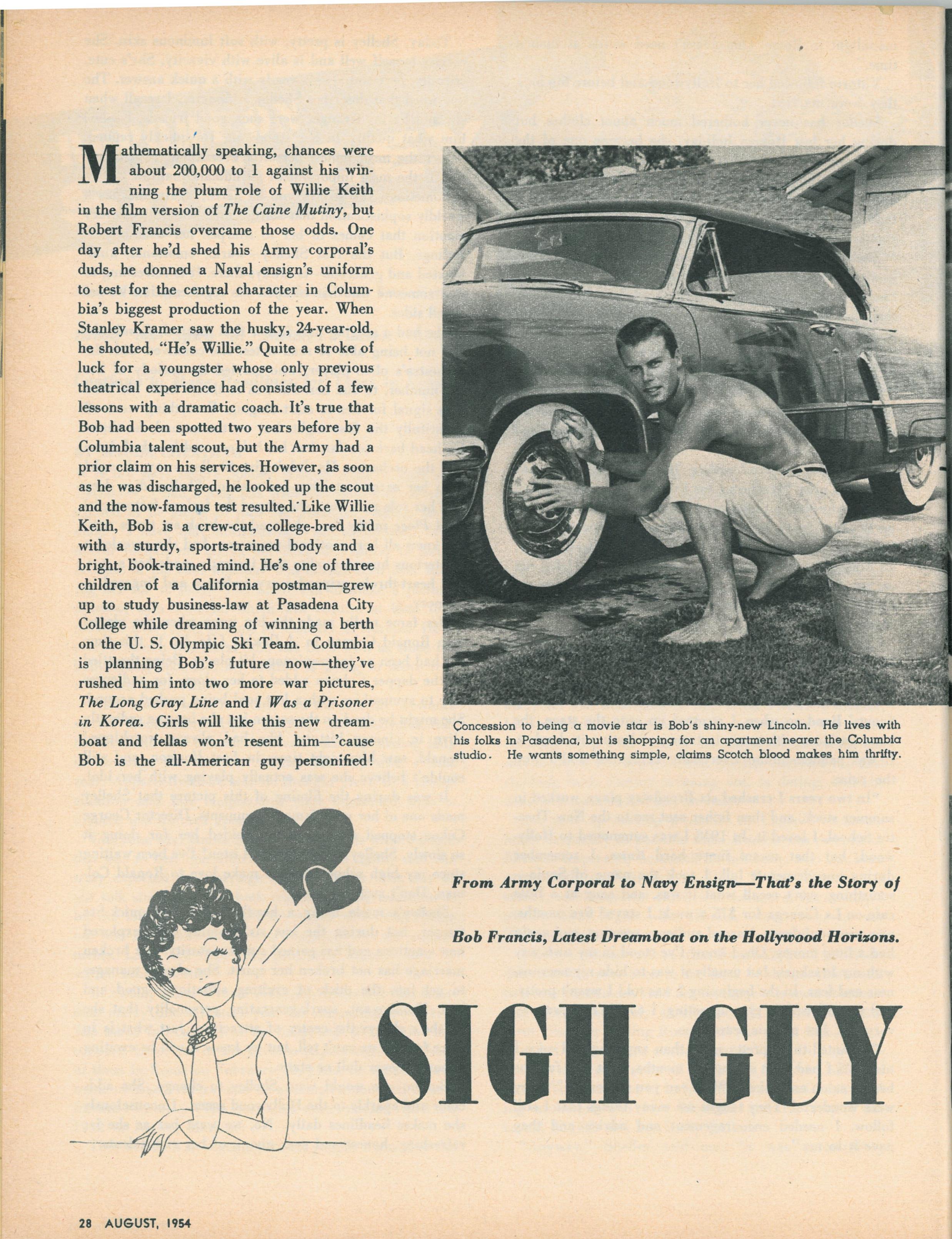

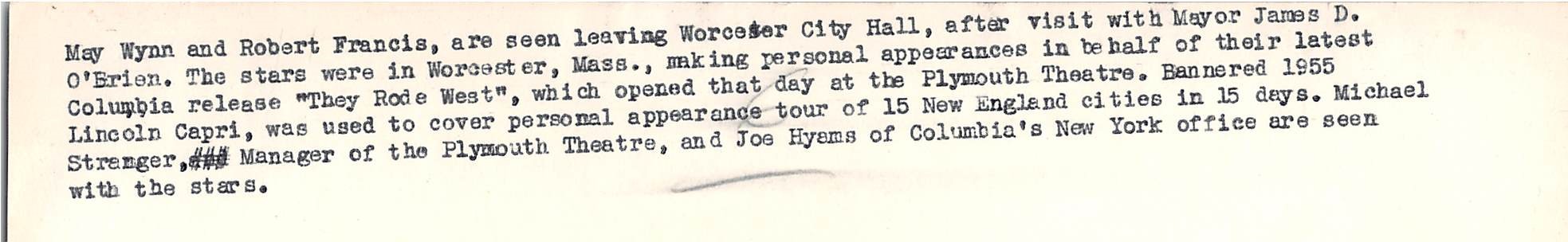

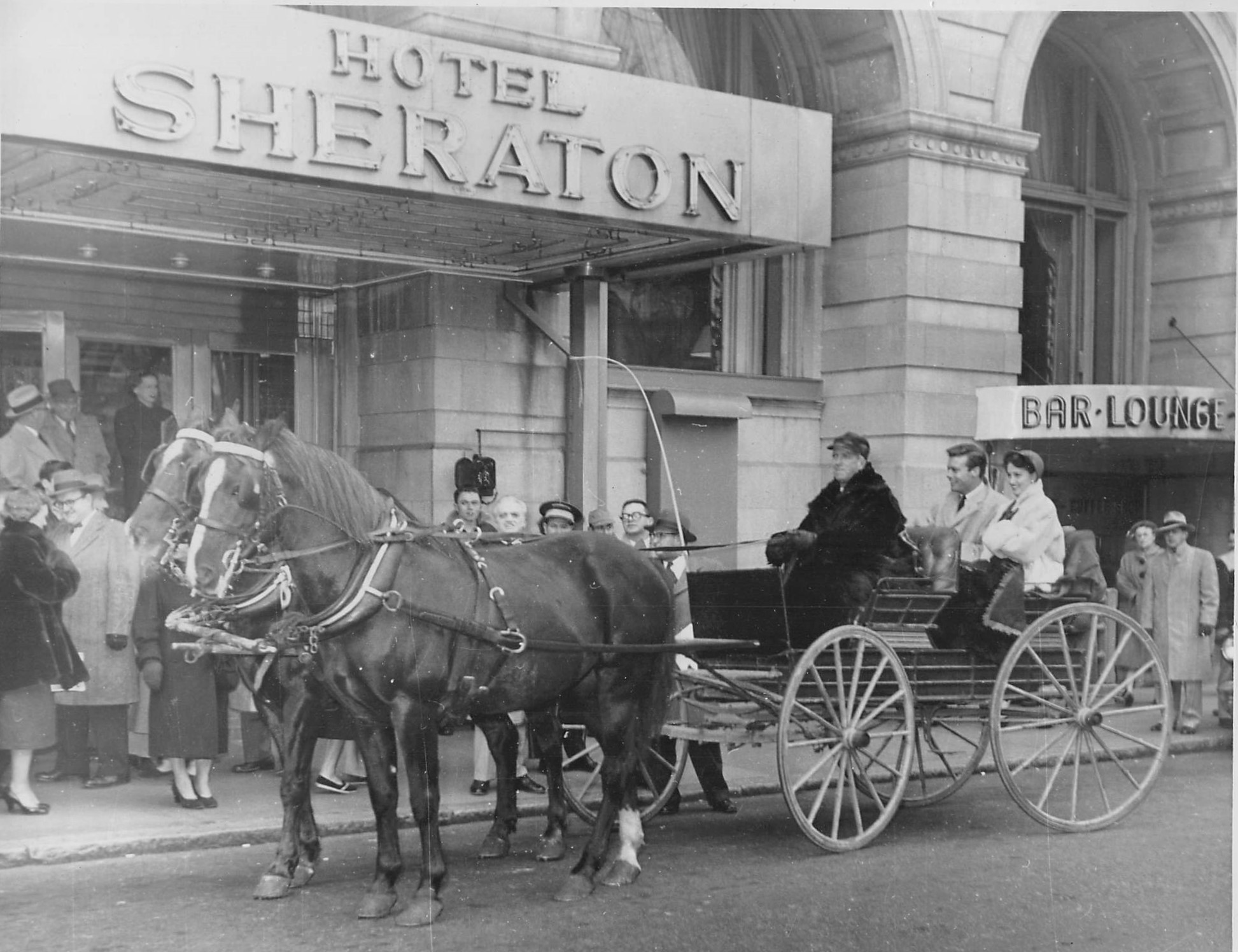

By May 1954, Bob had completed four films, but did not yet have a released film. Still, the publicity drums were being prepared for and with him. After completing The Long Gray Line, Bob entered another phase of “the making of a star” focused primarily on personal appearance tours. During June, July, and Aug. 1954, he (and often, May Wynn) traveled to promote The Caine Mutiny. He did a “solo” loop mostly by car (his newly purchased Cadillac). A stop in Salt Lake City around July 24, 1954, produced a Salt Lake City newspaper story, “Film Star ‘Shaloms’ Into S.L. For ‘Caine Mutiny’ Boost.” “…to climax a transcontinental publicity shalom….” He “…left New York two months ago and 19 cities ago, and has been ‘on a dead run ever since.’ He has an “…abundance of clean-cut personality and blue-eyed sincerity that project themselves so easily to a film audience.” That tour ended in Phoenix, Ariz., in early Aug. 1954 where he visited with his brother Bill and his family.

A second major personal appearance tour began in Sept. and took him to, among other cities, Bellevue, Neb., where he had Francis relatives.

In Dec. 1954, he and May Wynn did a New England tour for They Rode West, Following the release of The Long Gray Line in Feb. 1955, he attended the Washington and New York City premieres and then traveled throughout Fla.

“From the time I got out of bed until I crawled back to my hotel room after midnight, I did interviews and grinned for the camera until my jaws ached. It was more exhausting than making the movie…The promotion thing was about wearing the happy face – all the time.” (Hunter, p. 60)

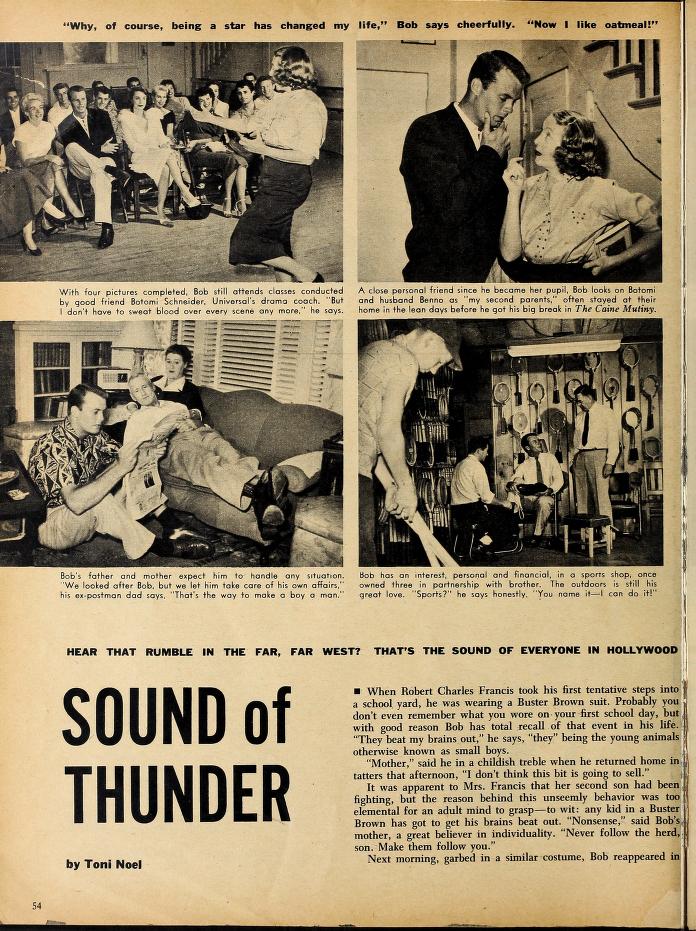

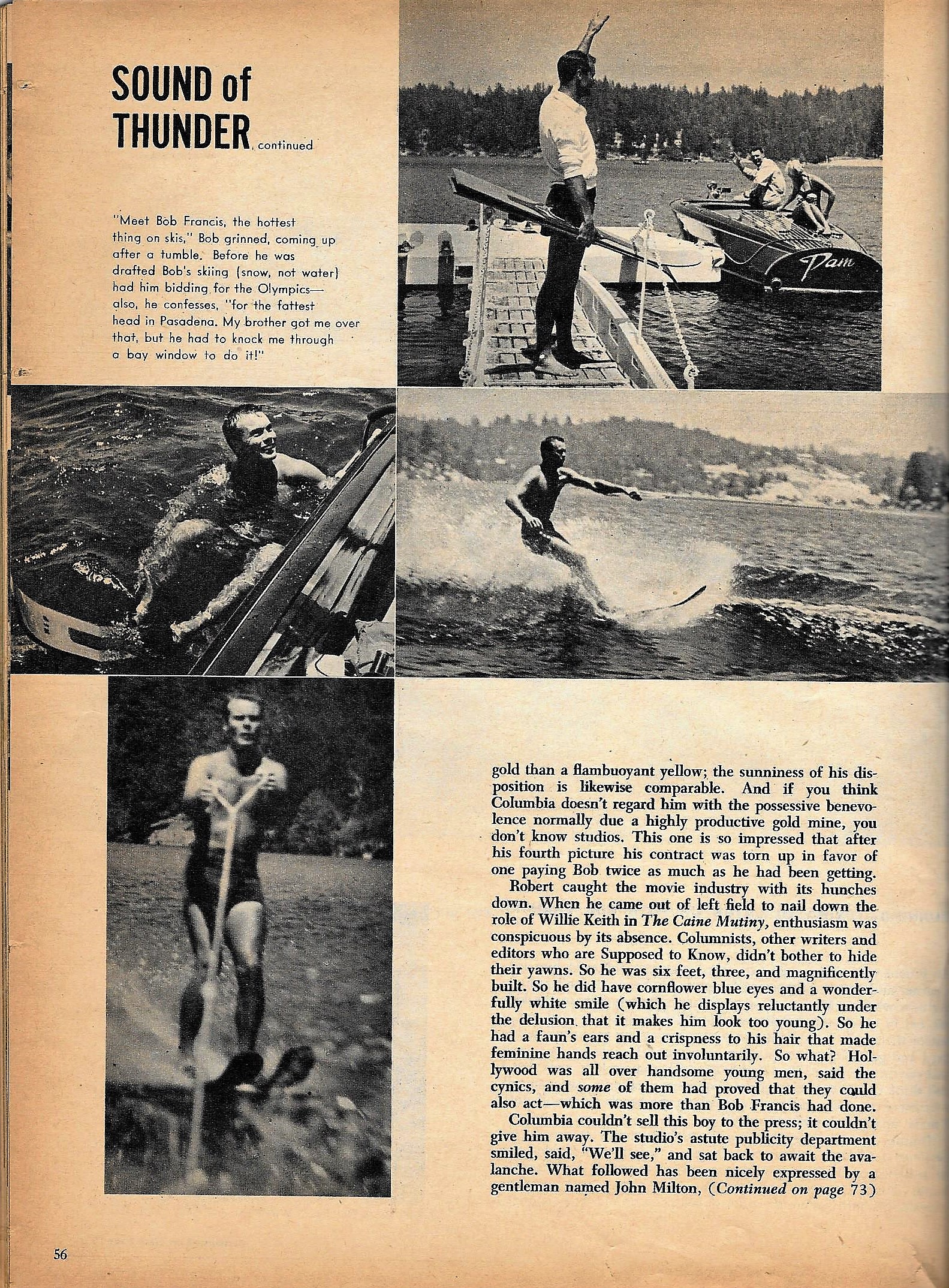

Aug. 1954

By the time this issue of Modern Screen, Aug. 1954 (on newsstands in early July 1954), appeared, Bob had received national press attention and had started a significant personal appearance tour for The Caine Mutiny. Note that this article makes extensive use of the official Columbia biography, extending and elaborating on it with interviews with Bob, his mother, his friends, and others. The amount of space allocated to a newcomer is unusual, but reveals the enormous effort by Columbia to create a new star with the help of fan magazines, especially Modern Screen. The photo features Bob in his Caine Mutiny haircut, c. Summer 1953.

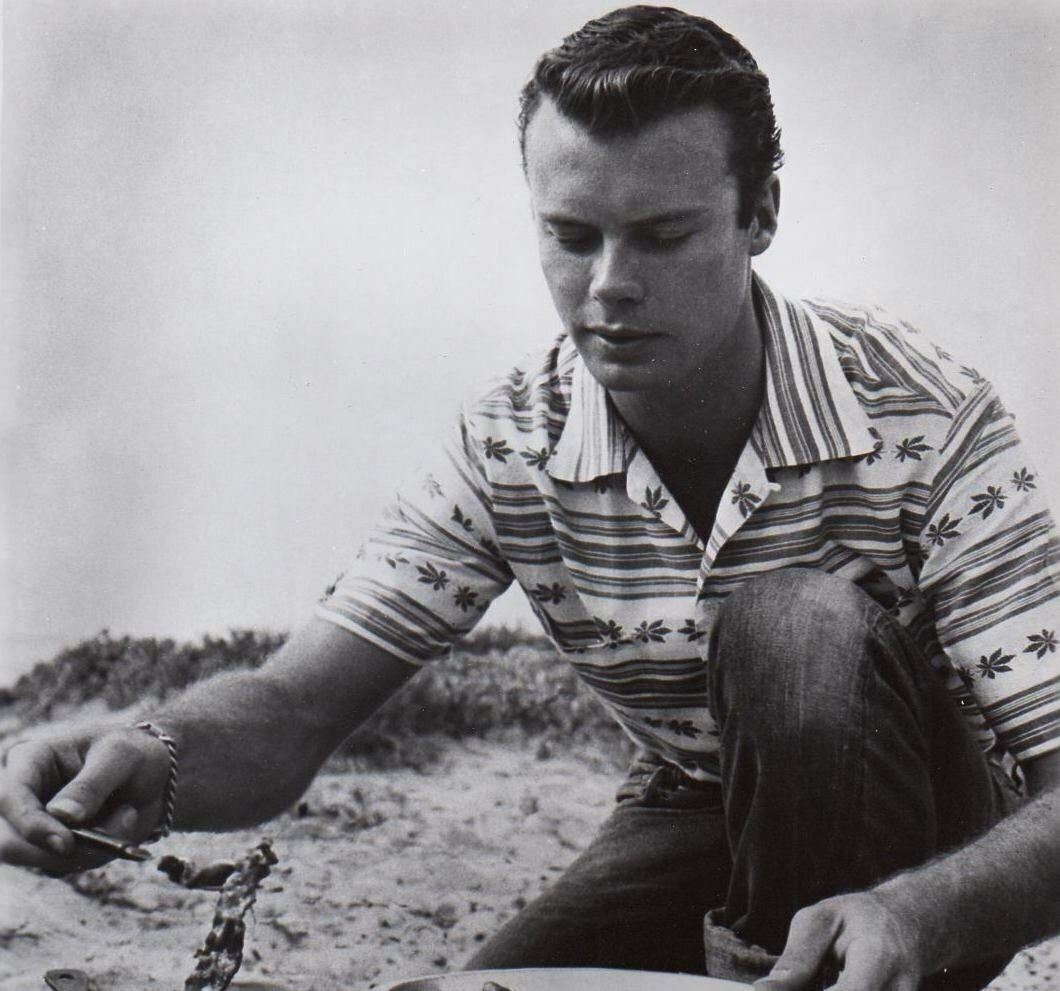

Spring/Summer 1953

Bob sports his Caine Mutiny haircut.

Spring/Summer 1953

Appears as if Bob has just gotten his Caine Mutiny hair cut.

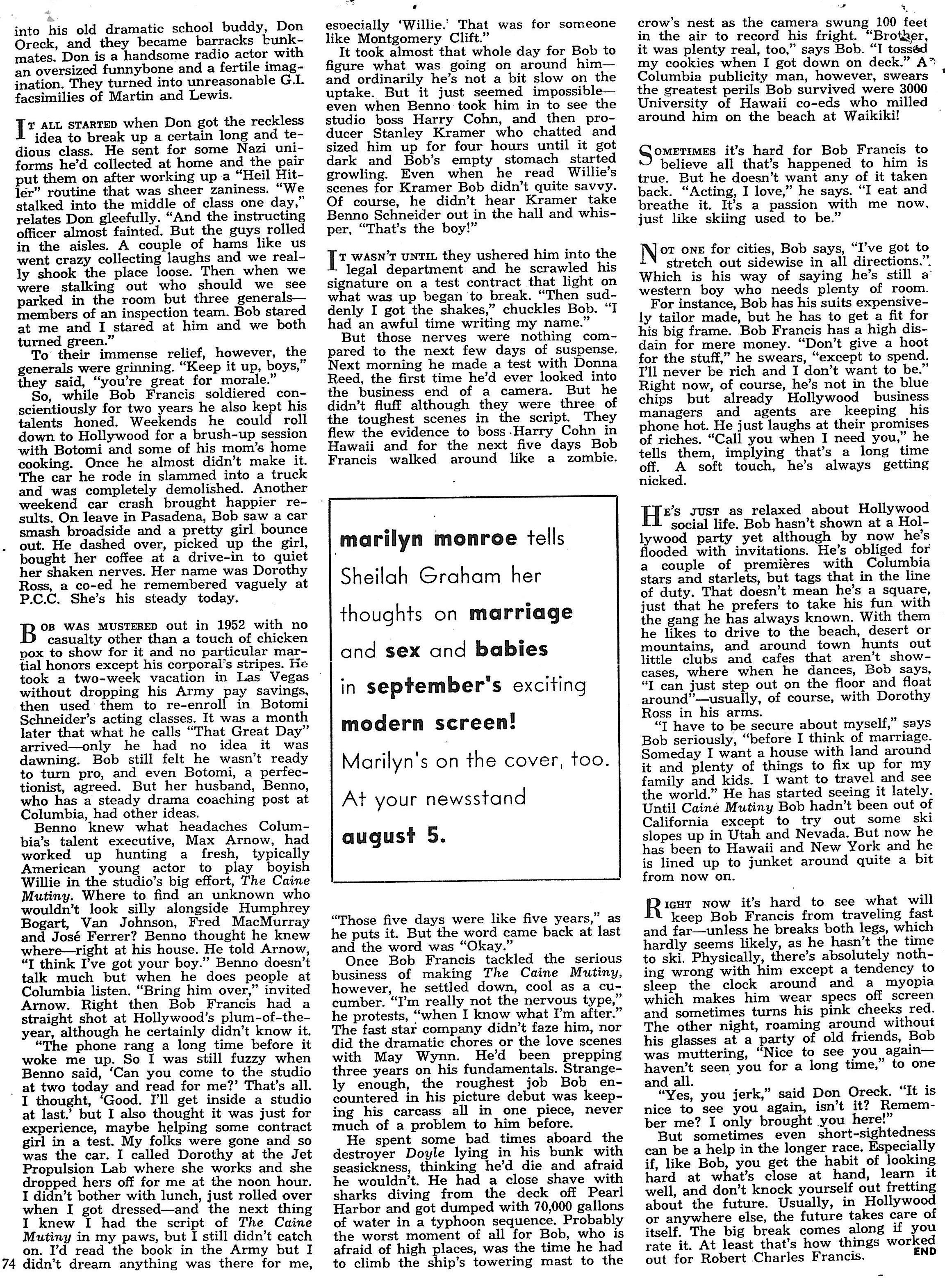

Spring/Summer 1953

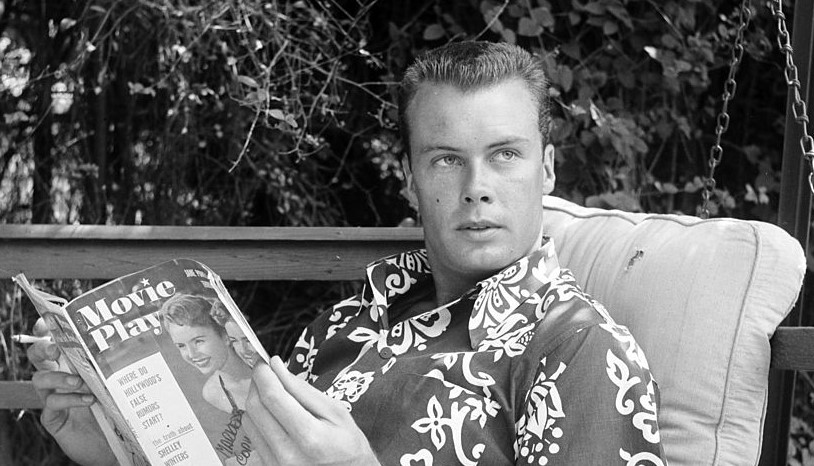

This shirt appears in a number of photos including the photo with “Bob Francis,” Modern Screen, Aug. 1954.

Summer 1953

This photo appears in print in July 1954. Location: Bob’s bedroom at his parents’ home in Pasadena. Columbia Pictures.

Summer 1953

This photo appears in print in July 1954. Location: The back yard at his parents’ home in Pasadena. That’s his Lincoln in the background. (He purchased a Cadillac while on a personal appearance tour, then drove it across part of the U.S.A. while touring.)

Bob’s sister Lillian says this is the last of trees in the yard at 212 S. Grand Oaks Ave.

“It was a walnut tree and we spent a lot of time up in the tree and threw shells all over the ground. When my Dad came home, he made us pick them all up.”

Source: Lillian Francis Robins, interview, May 11, 1991.

The Gallery: January-June 1954

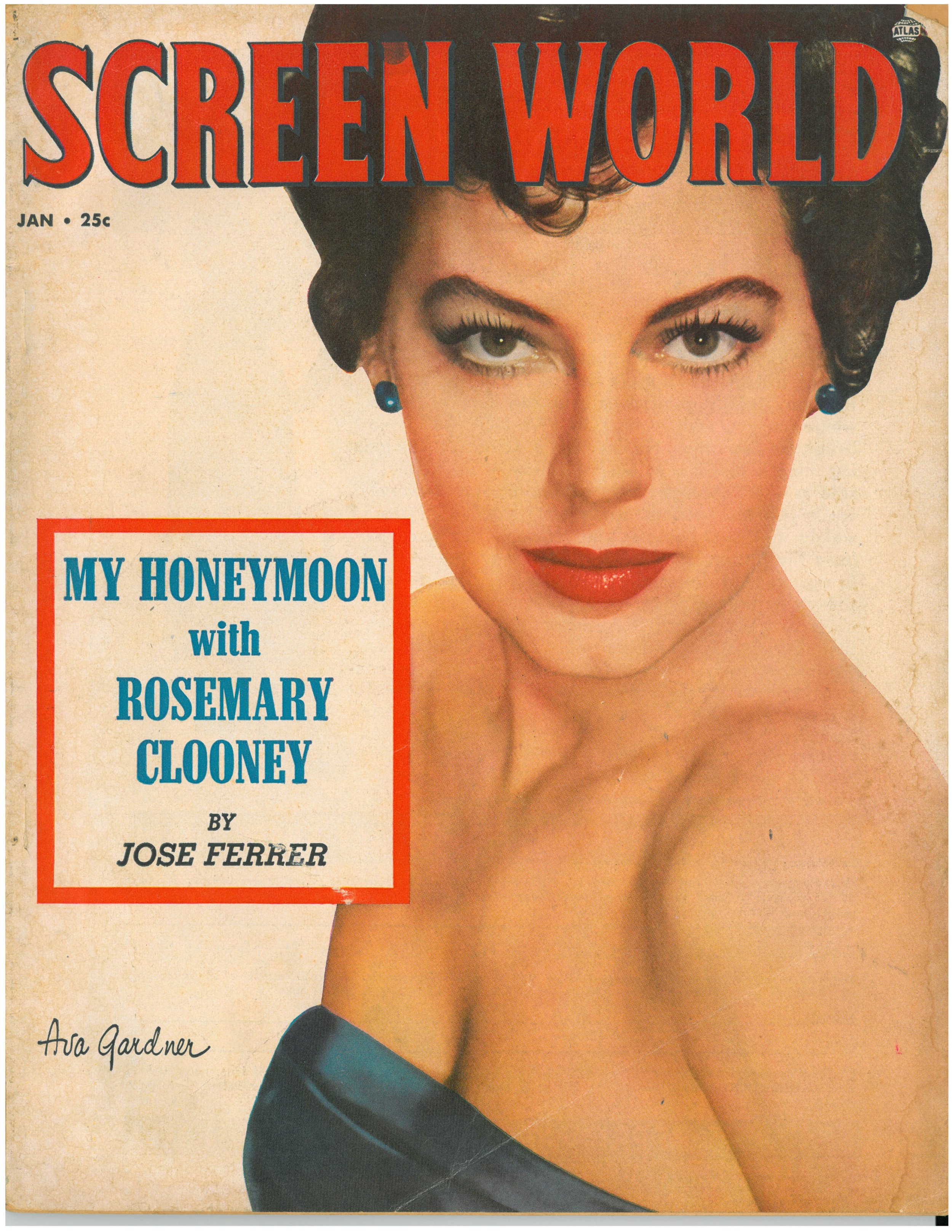

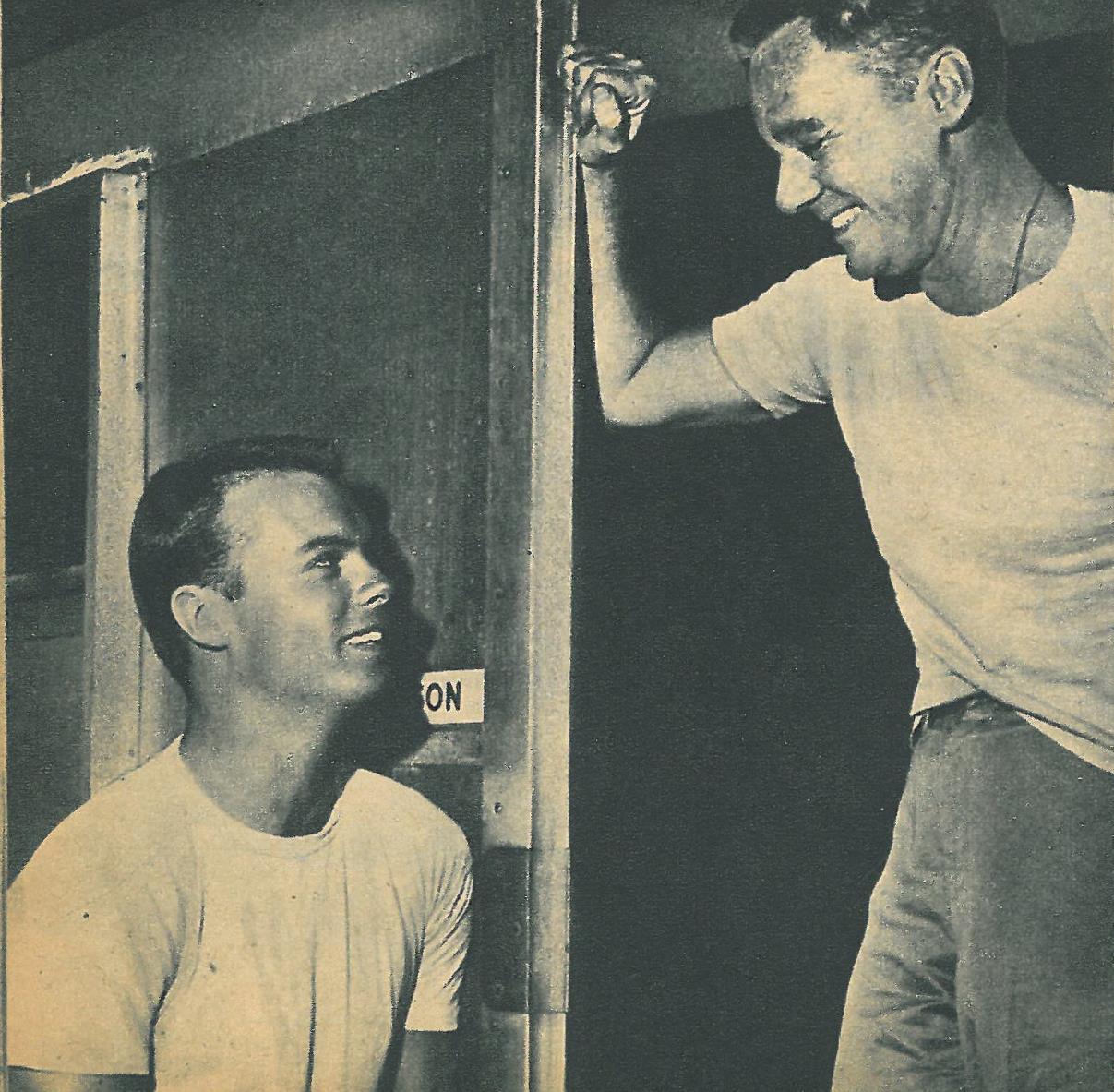

Jan. 1954

Perhaps Bob’s earliest appearance in a fan magazine, Screen World, Jan. 1954 (on newsstands in early Dec. 1953), when Bob was just finishing They Rode West. Photo of Bob and Van Johnson dates from Summer 1953 during Caine filming. Johnson had had his own fast rise to stardom at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the early and mid-1940s. He said, “(The Studio System at MGM) was one big happy family and a little kingdom. Everything was provided for us, from singing lessons to barbells. All we had to do was inhale, exhale and be charming. I used to dread leaving the studio to go out into the real world, because to me the studio was the real world.”

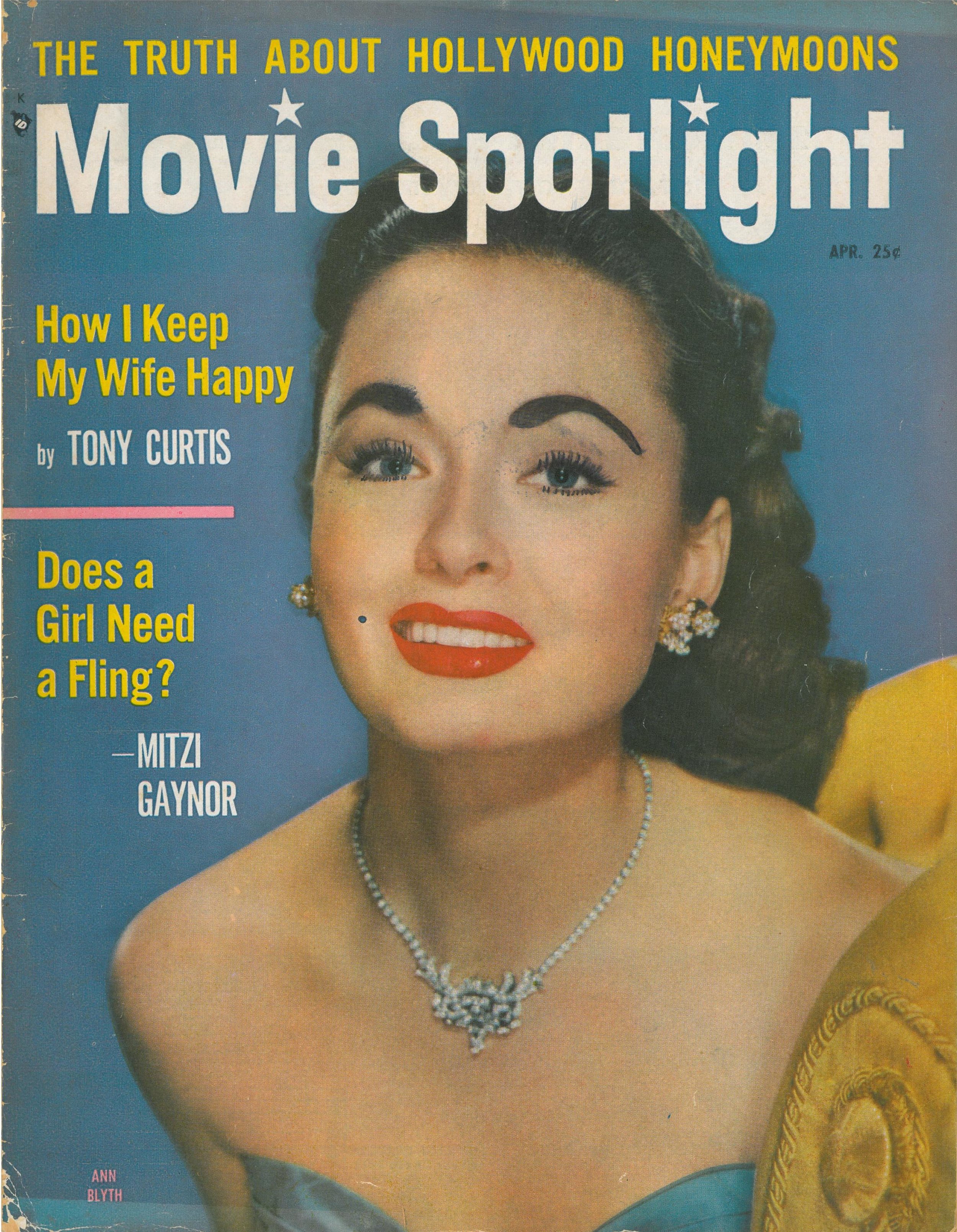

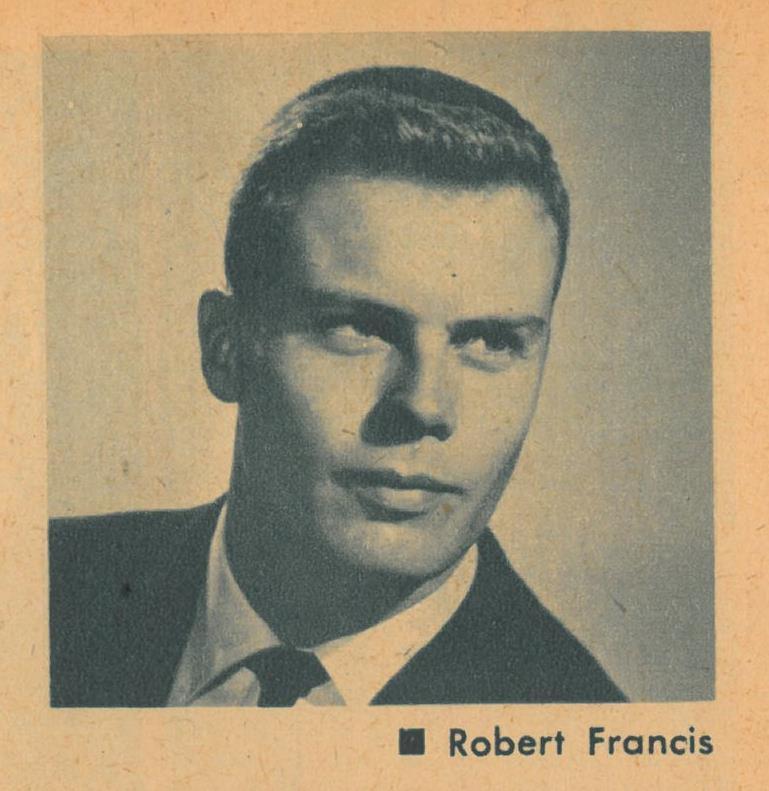

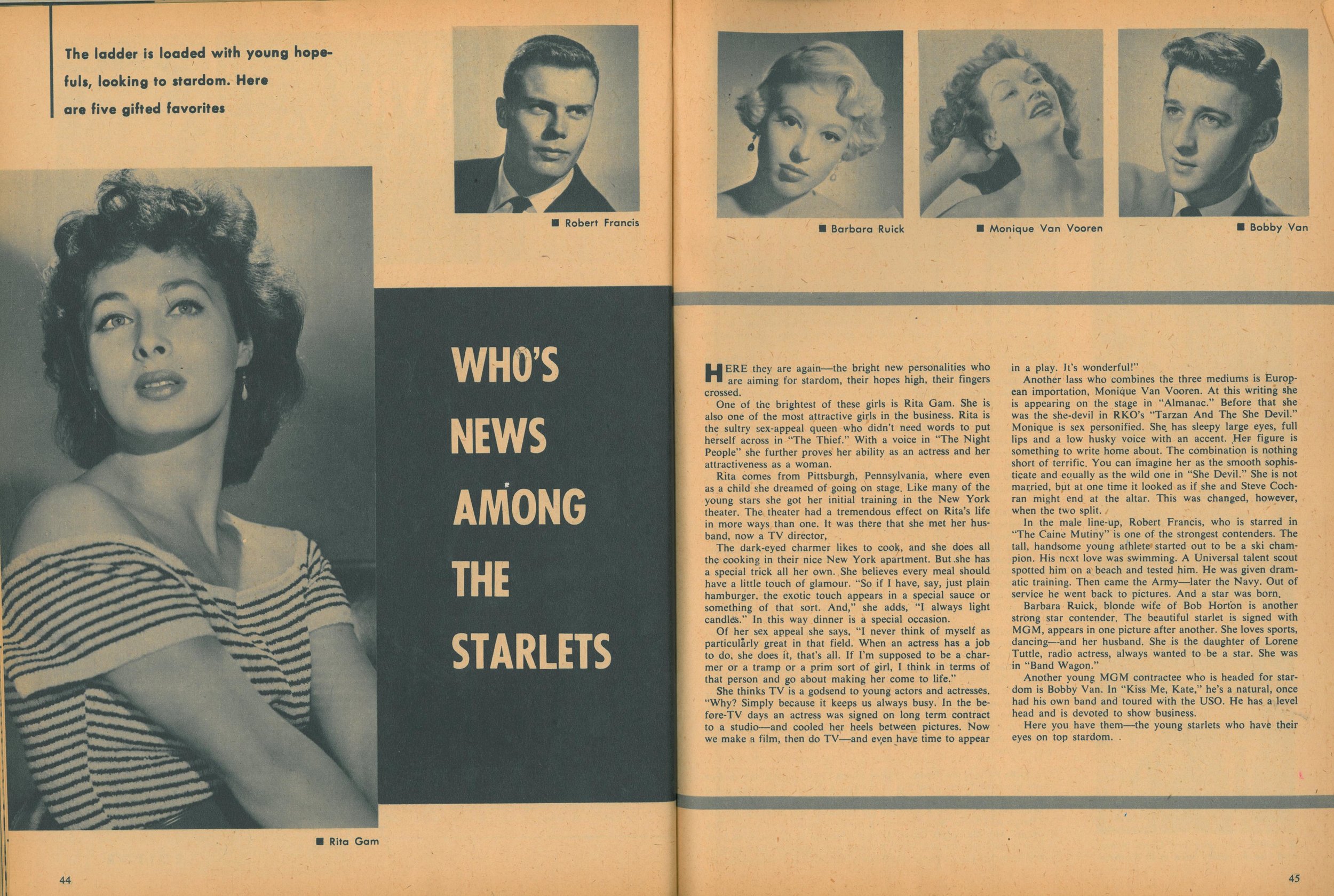

April 1954

Movie Spotlight, April 1954 (available on newsstands in early March 1954). Photo: c. Spring 1953 before Caine Mutiny haircut.

“What is a movie star? It may be more appropriate to phrase the question in the past tense, as an acknowledgement that the old breed is dying out and also as a valedictory tribute to one its finest specimens. Because whatever the definition — a great performer; a larger-than-life personality; a sex symbol — the picture next to the dictionary entry might as well be of Tony Curtis in his prime, with his dark eyes, full lips and lush head of hair.

“Mr. Curtis…was among the purest and most authentic examples of what a movie star meant in postwar Hollywood…Which is also to say, of course, that he fundamentally — brazenly — impure and inauthentic, an artificial, hybrid creature synthesized out of ambition, good looks and canny publicity. Tony Curtis was a marvelous invention, right down to the name, which replaced Bernard Schwartz, the one he was born with. …” A.O. Scott, “Marvelous Invention of Movie Make-Believe,” New York Times, Oct. 2, 2010.

[Bob’s story is not the same. No name change. Some ambition and good looks. Uncanny luck. Definitely not “…impure and inauthentic, an artificial, hybrid creature synthesized out of ambition, good looks and canny publicity.”]

“Mr. Curtis belonged to the last generation of stars discovered and developed under the studio system. ..began working his way up from bit roles in small films, allowing the studio to shape his image and manage his appearances in the fan magazines.” Dave Kehr, New York Times, Oct. 3, 2010

Spring 1953

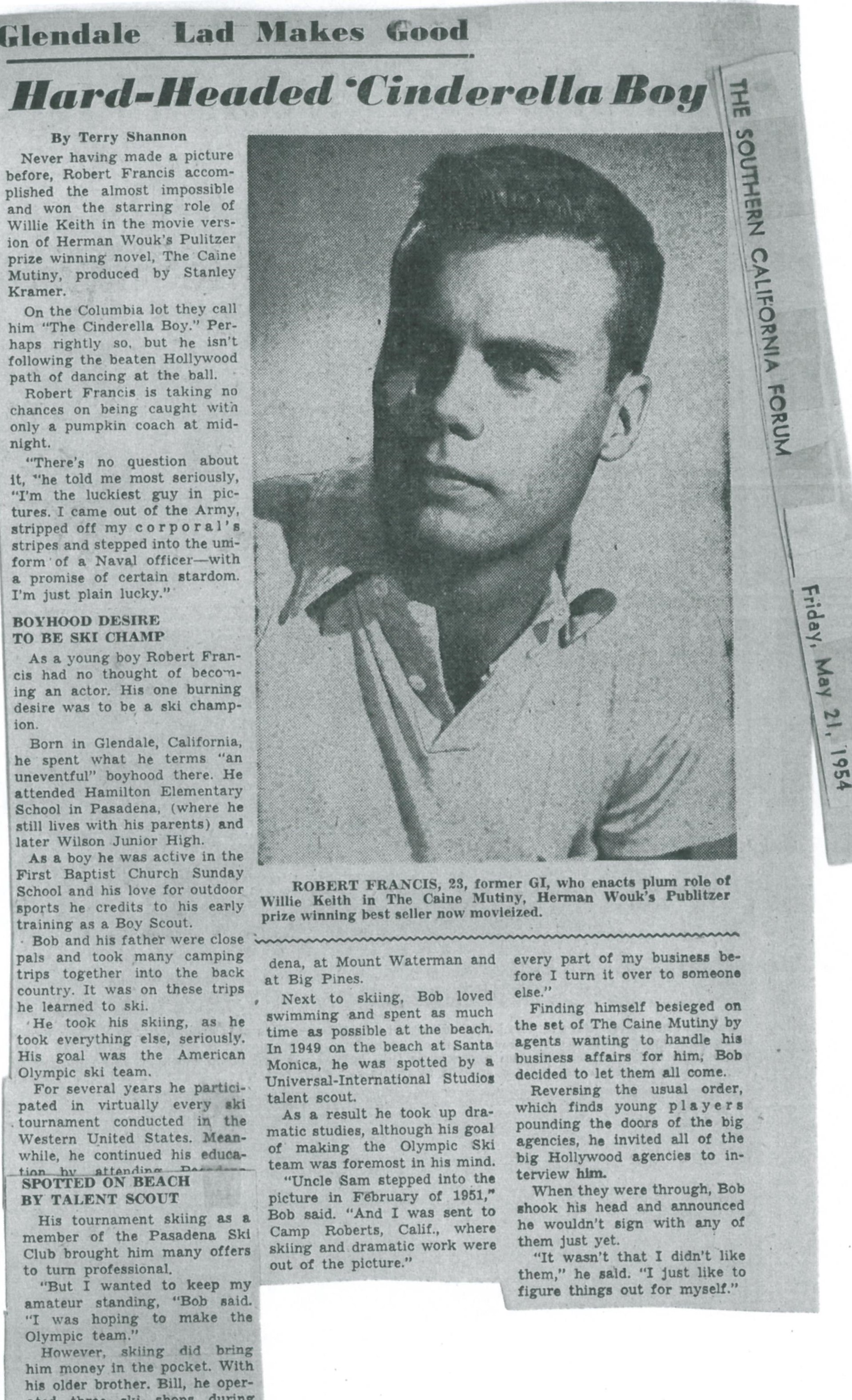

The Southern California Forum, Friday, May 21, 1954. Note extensive use of the official Columbia biography.

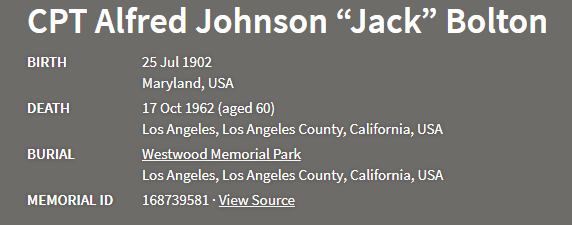

Bob did have an agent at the time of his death in 1955, “Jack” Bolton of (Music Corporation of America (MCA) It published music, booked acts, ran a record company, represented film, television, and radio stars, and eventually produced and sold television programs to the three major networks. Maureen O’Hara and John Ford, star and director of The Long Gray Line, were Bolton’s clients; they may have suggested him to Bob or vice versa.

Winter/Spring 1954

Screen Life, publication date unknown, perhaps a fall 1954 issue. Bob’s first trip to New York City was probably in Spring 1954 when he was filming The Long Gray Line at West Point.

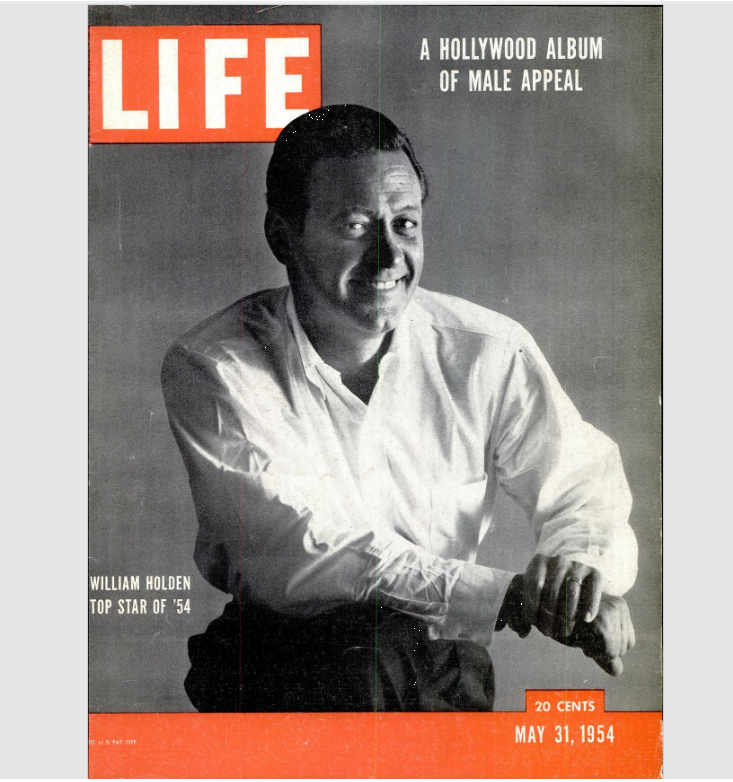

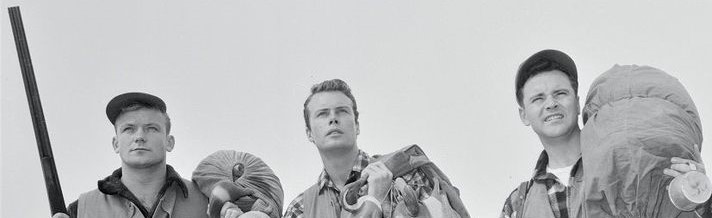

Bob’s first national exposure*. Life, May 31, 1954. Photo made in Winter/Spring 1954 when Bob was working on The Bamboo Prison and The Long Gray Line.

In their autobiographies both Robert Wagner and Tab Hunter mention this May 31, 1954, Life magazine article. While Life often covered movies and movie stars, the attention to Hollywood’s younger actors was an important step up the ladder in that Life as a national, general circulation publication introduced these young men to a much larger audience, the parents and grandparents of the teenagers who read movie fan magazines.

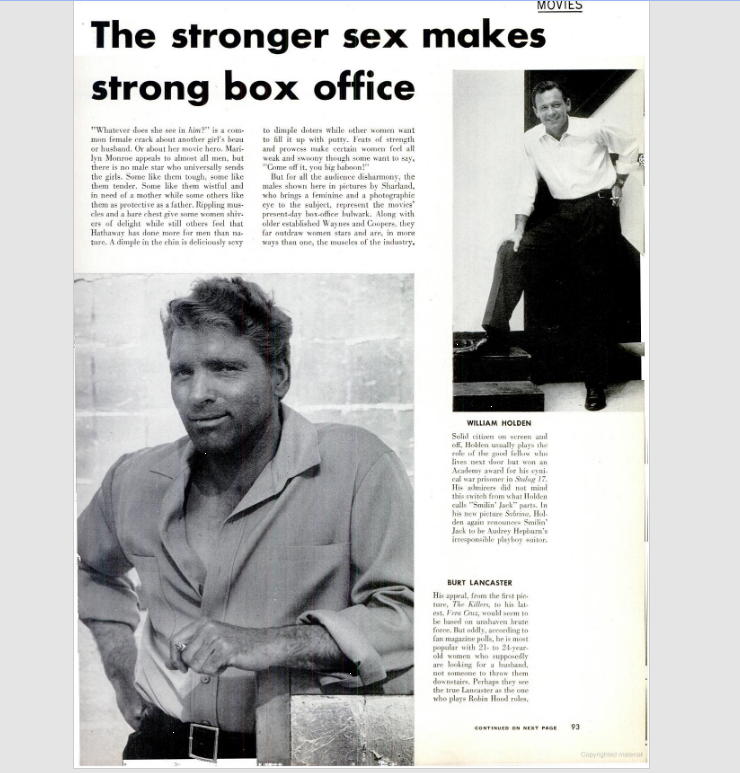

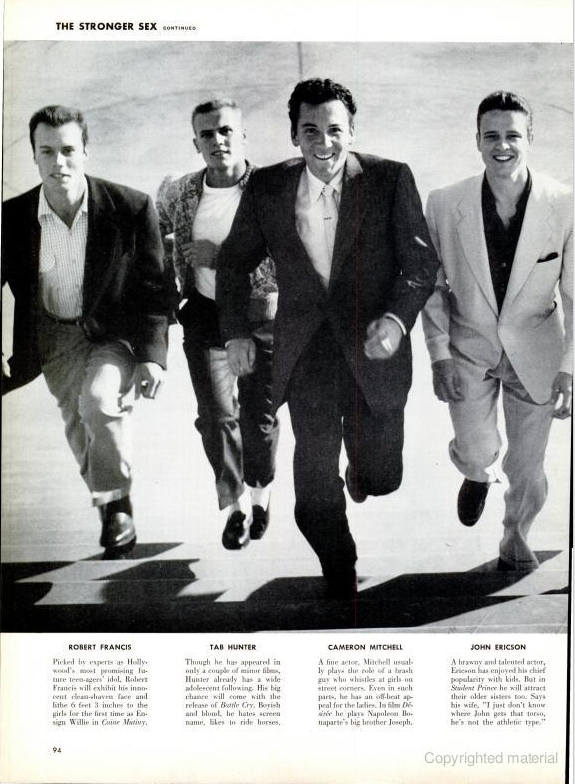

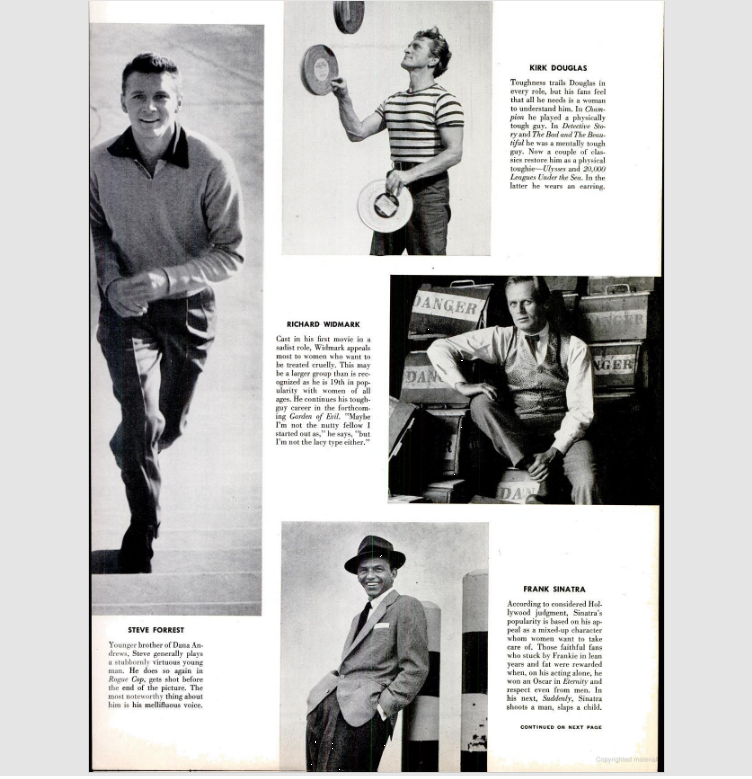

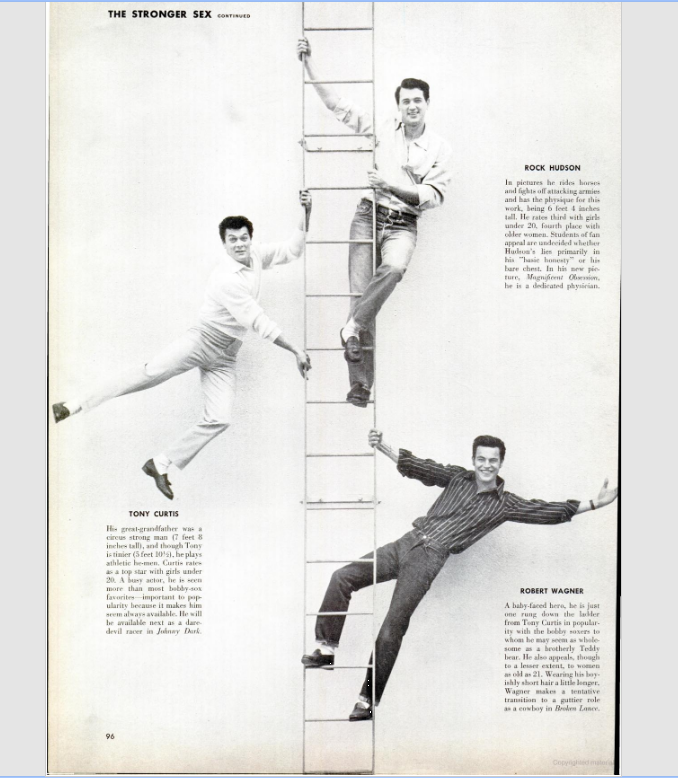

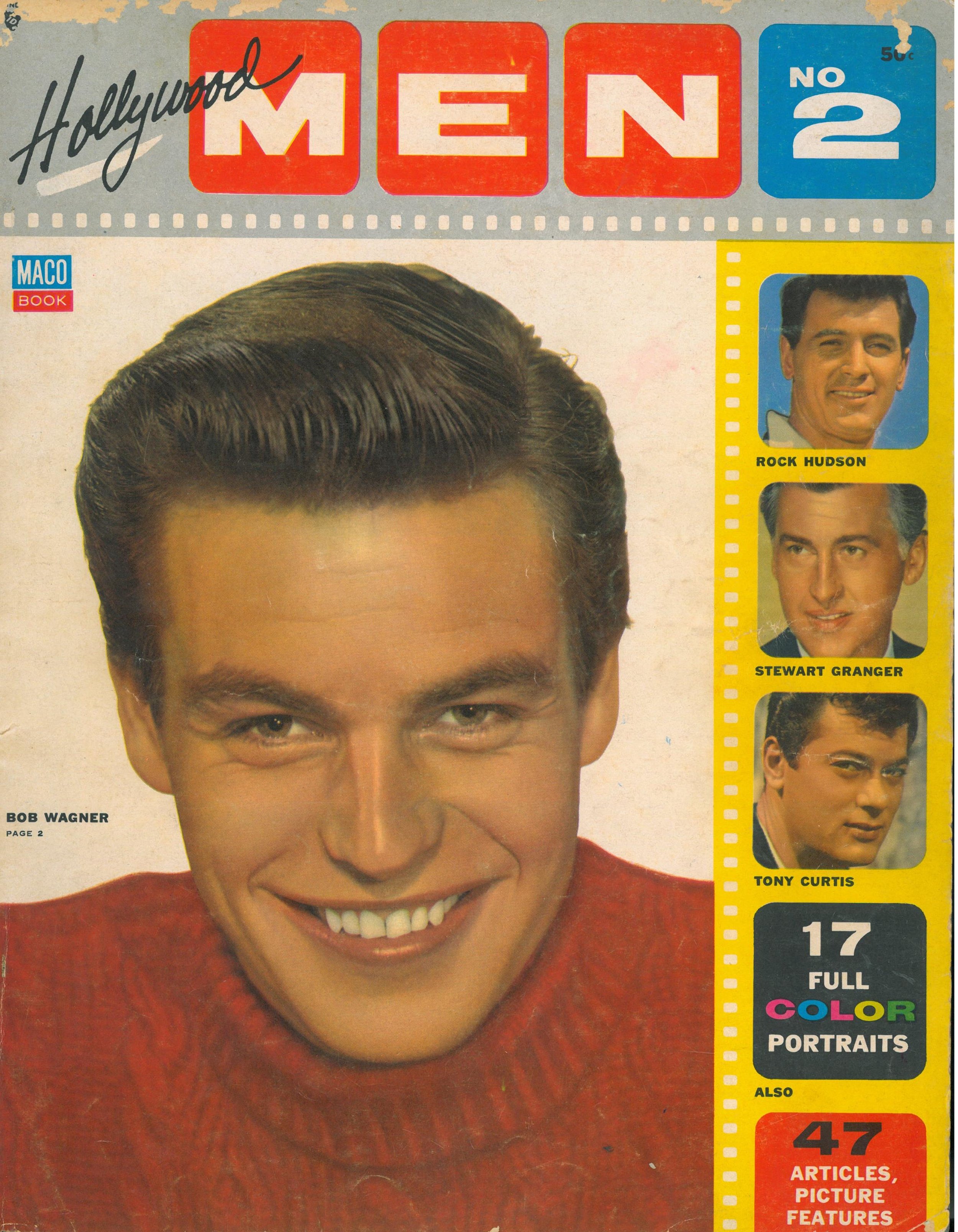

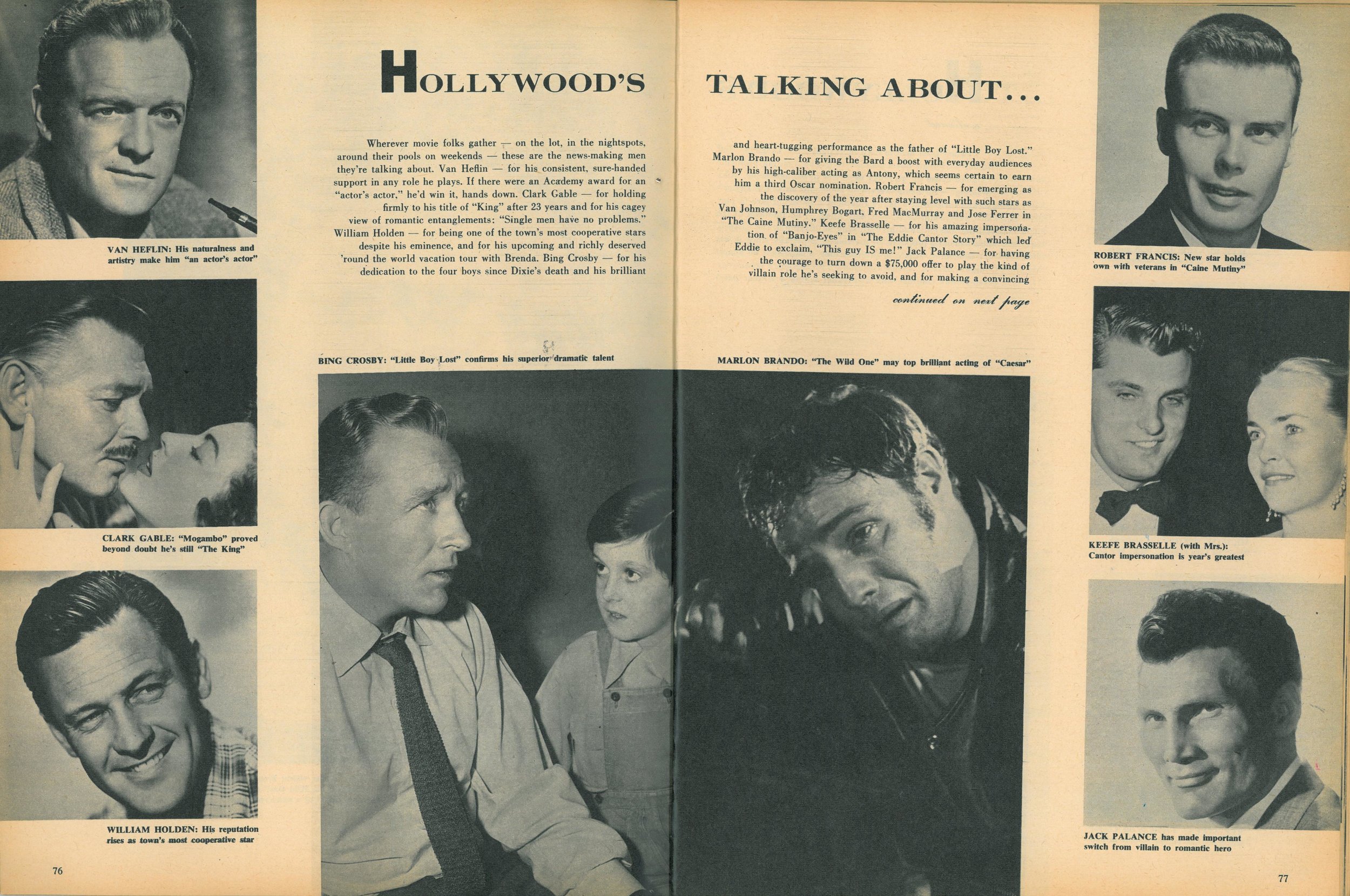

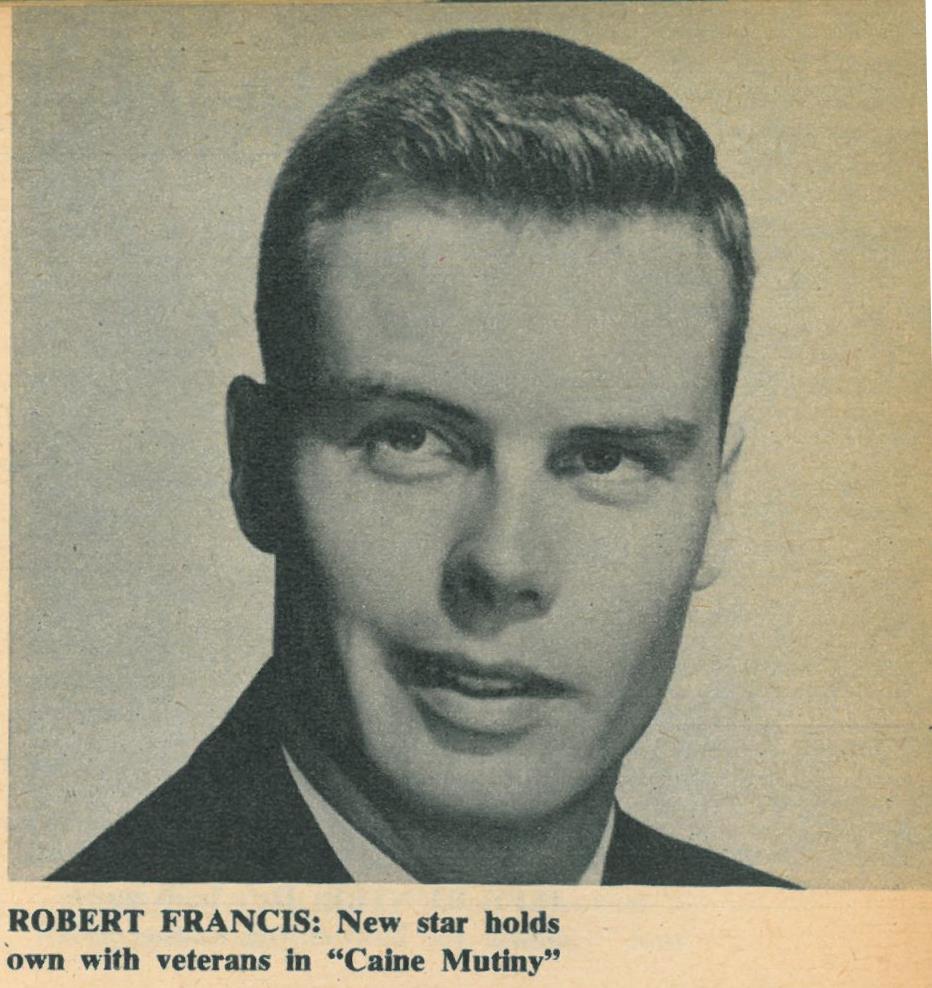

“…Life published a big featured called ‘The Stronger Sex,’ spotlighting Hollywood’s next generation of leading men. Christened the Big Three heartthrobs for the bobbysoxer set were Tony Curtis, Robert Wagner, and Rock Hudson…On the following page was the next rank of contenders, in a footrace up a flight of stairs: Robert Francis, Cameron Mitchell, John Ericson, Steve Forrest — and Tab Hunter…This kind of publicity, in a mainstream magazine with Life’s huge circulation….” (Hunter, p. 101) [The actual layout presented William Holden and Burt Lancaster and then the “contenders.” The last page of the feature shows Hudson, Curtis, and Wagner on a fire escape.]

*The Caine Mutiny had been the focus of an article in Collier’s magazine in Nov. 1953, but Bob was not highlighted as he was by Life.

“…I’d get my first inkling of how the publicity machine worked. I hadn’t even finished making my first movie (Island of Desire), but already fans were lining up in front of the building. They’d ask for an autograph or to have a picture taken with me. Sometimes they’d sneak snapshots of me coming and going. United Artists, it seemed, was staging a big buildup in advance of the movie’s release.” (Hunter, p. 58)

Bob’s caption: “Picked by experts as Hollywood’s most promising future teen-agers’ idol, Robert Francis will exhibit his innocent, clean-shaven face and lithe 6 feet 3 inches to the girls for the first time as Ensign Willie in Caine Mutiny.”

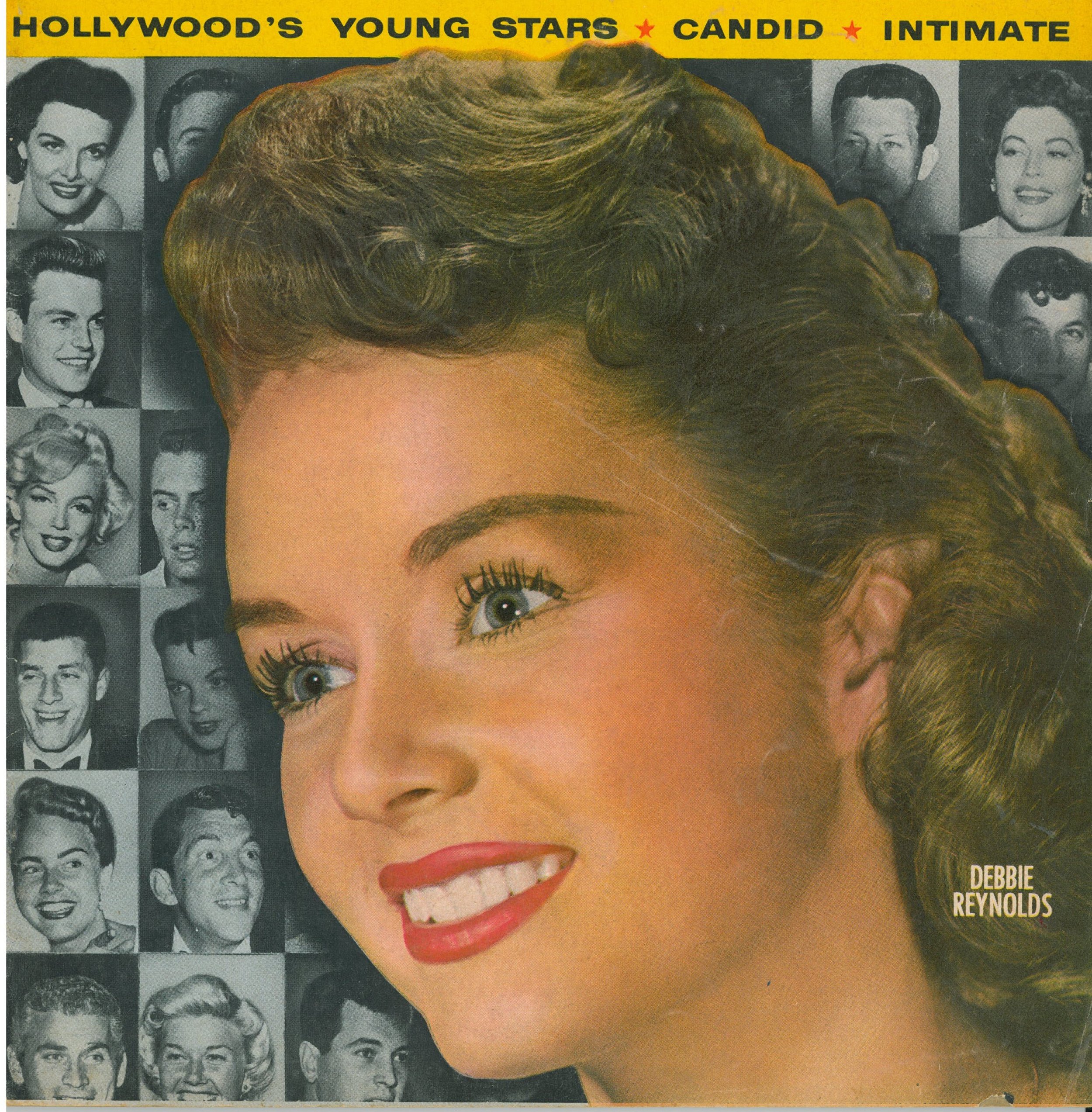

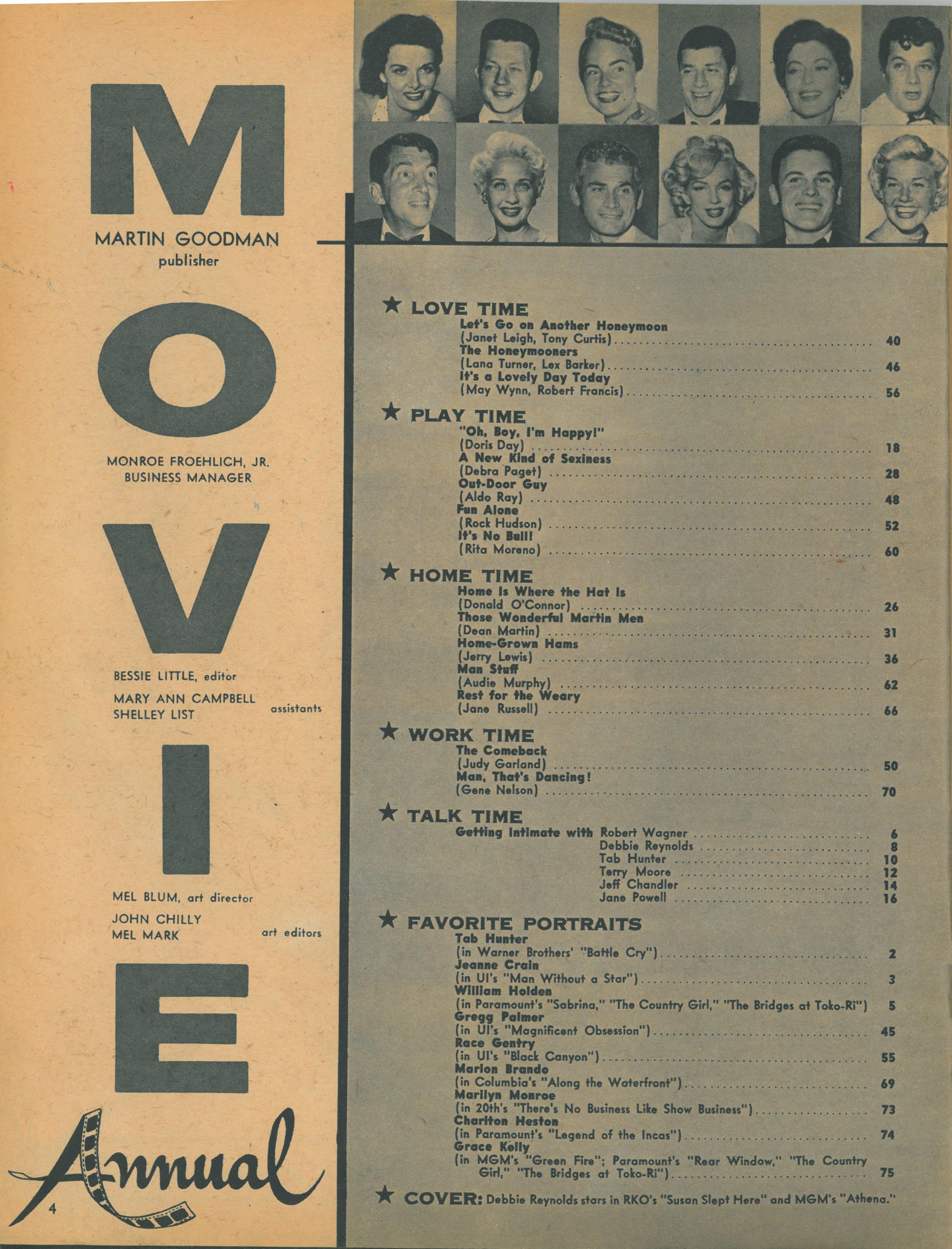

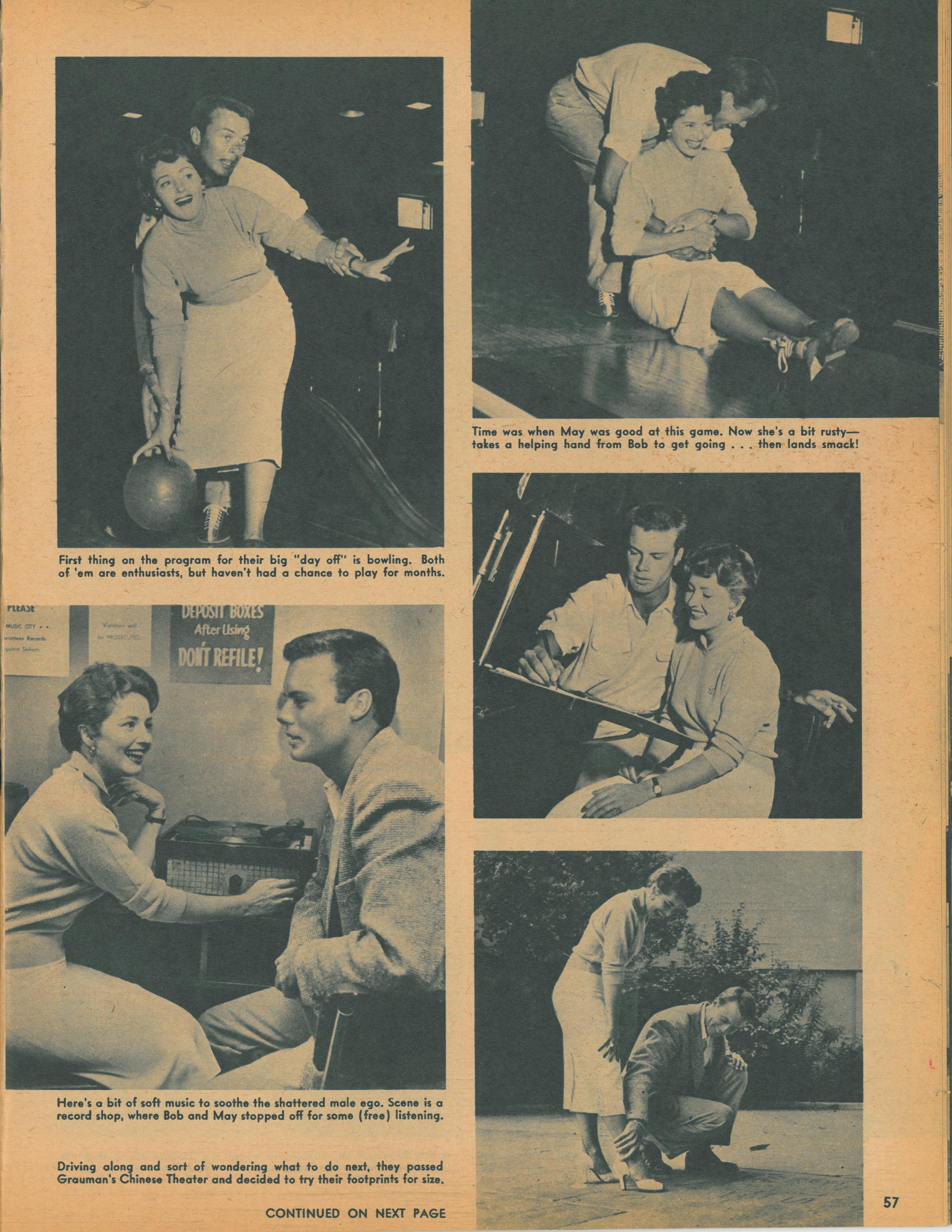

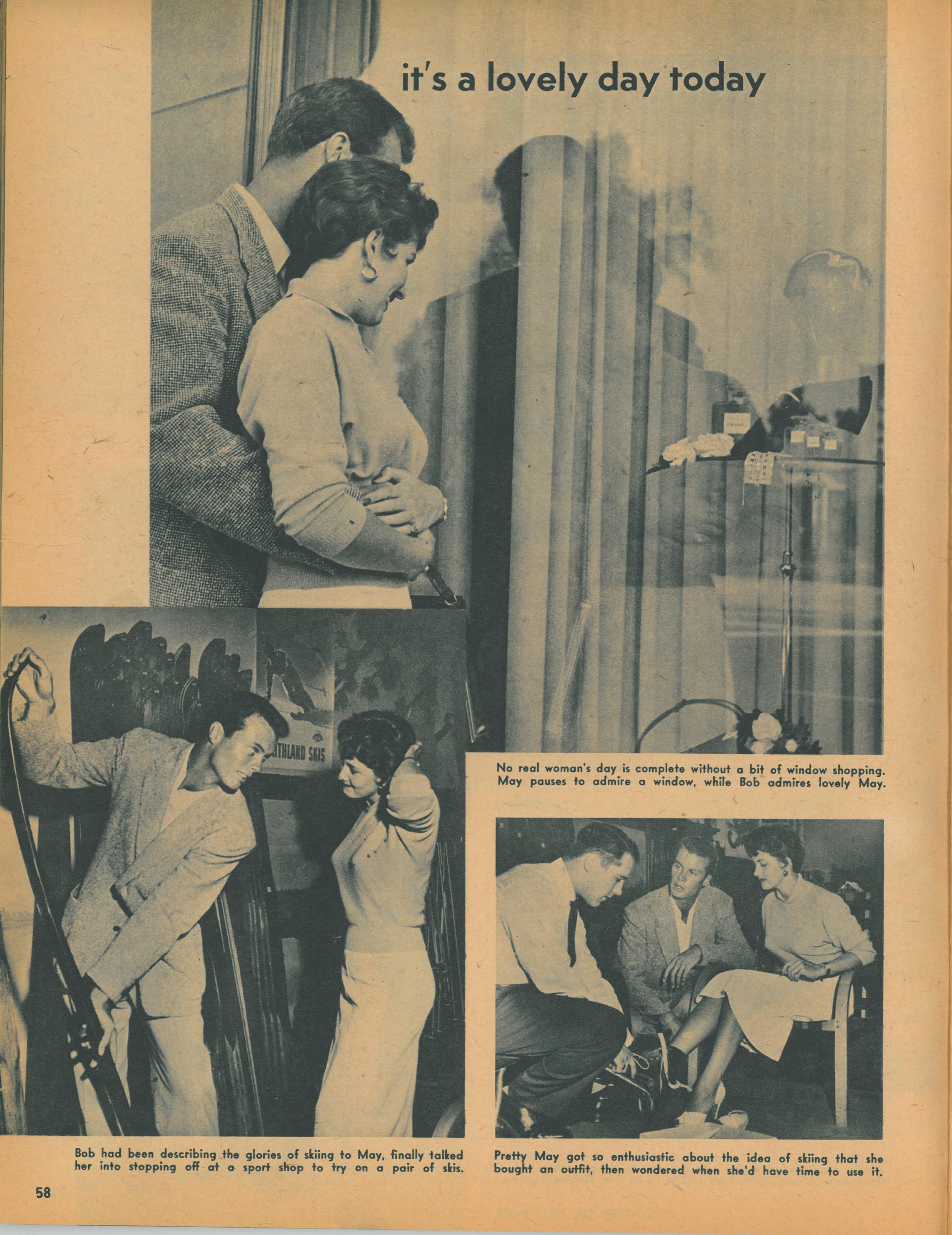

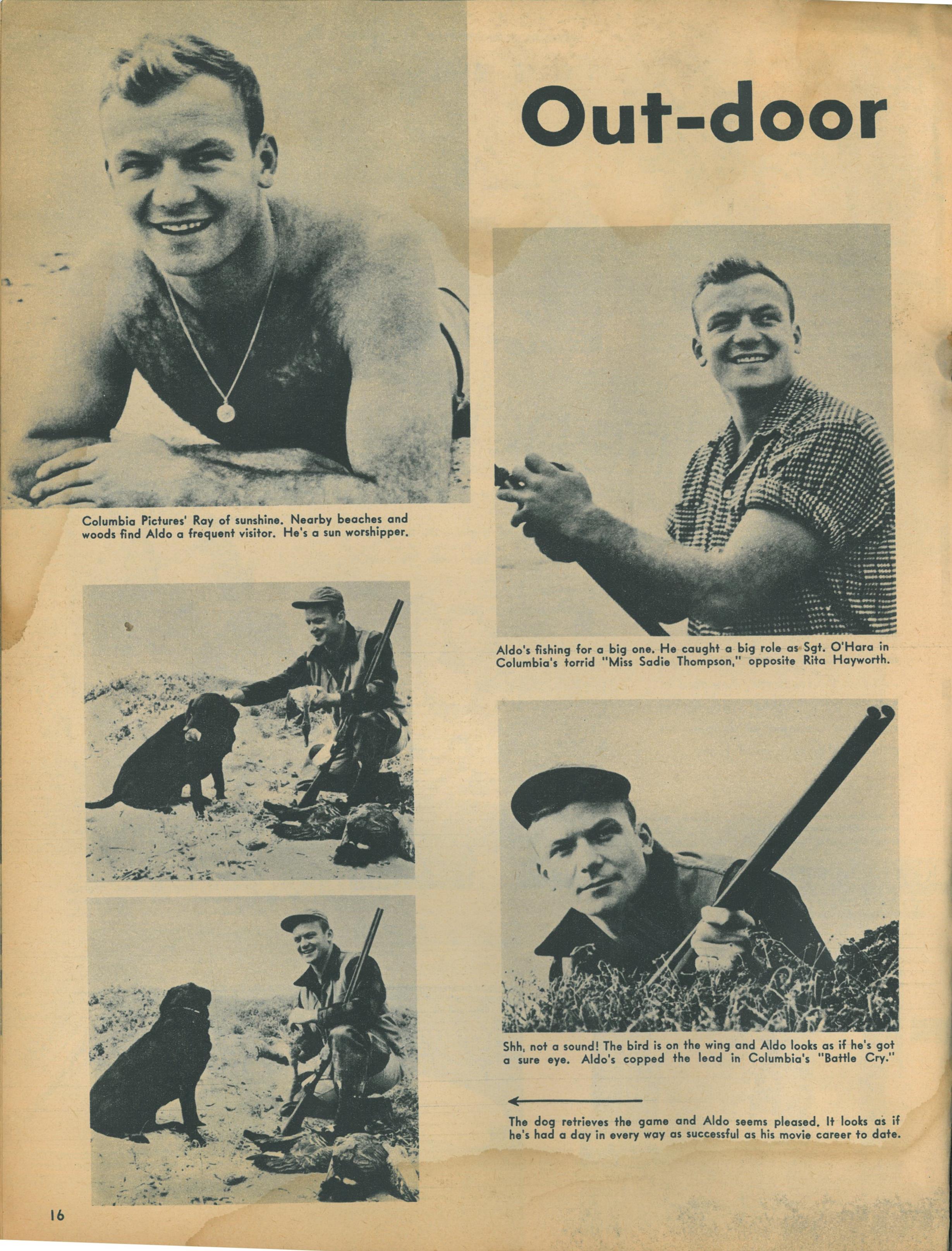

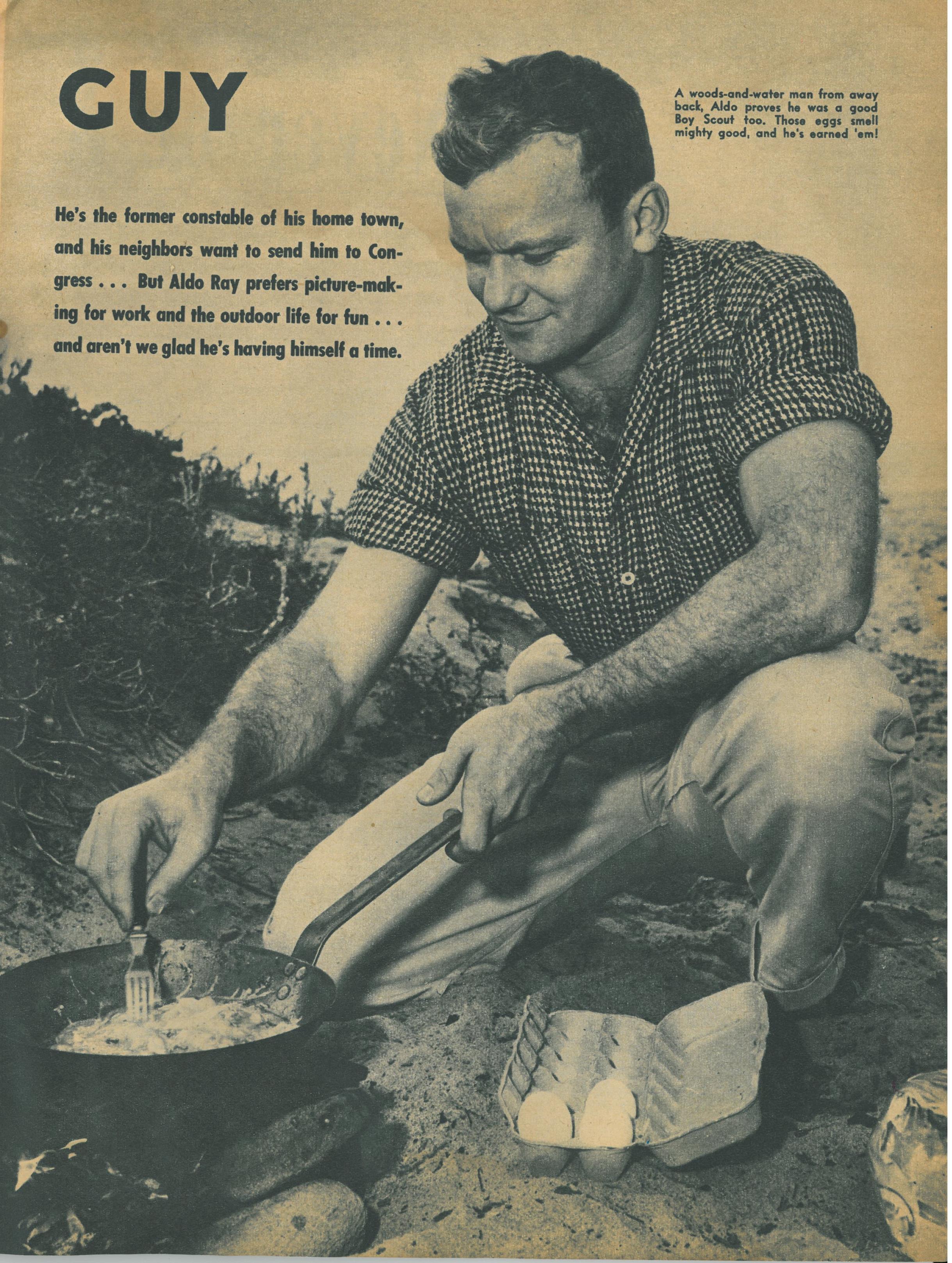

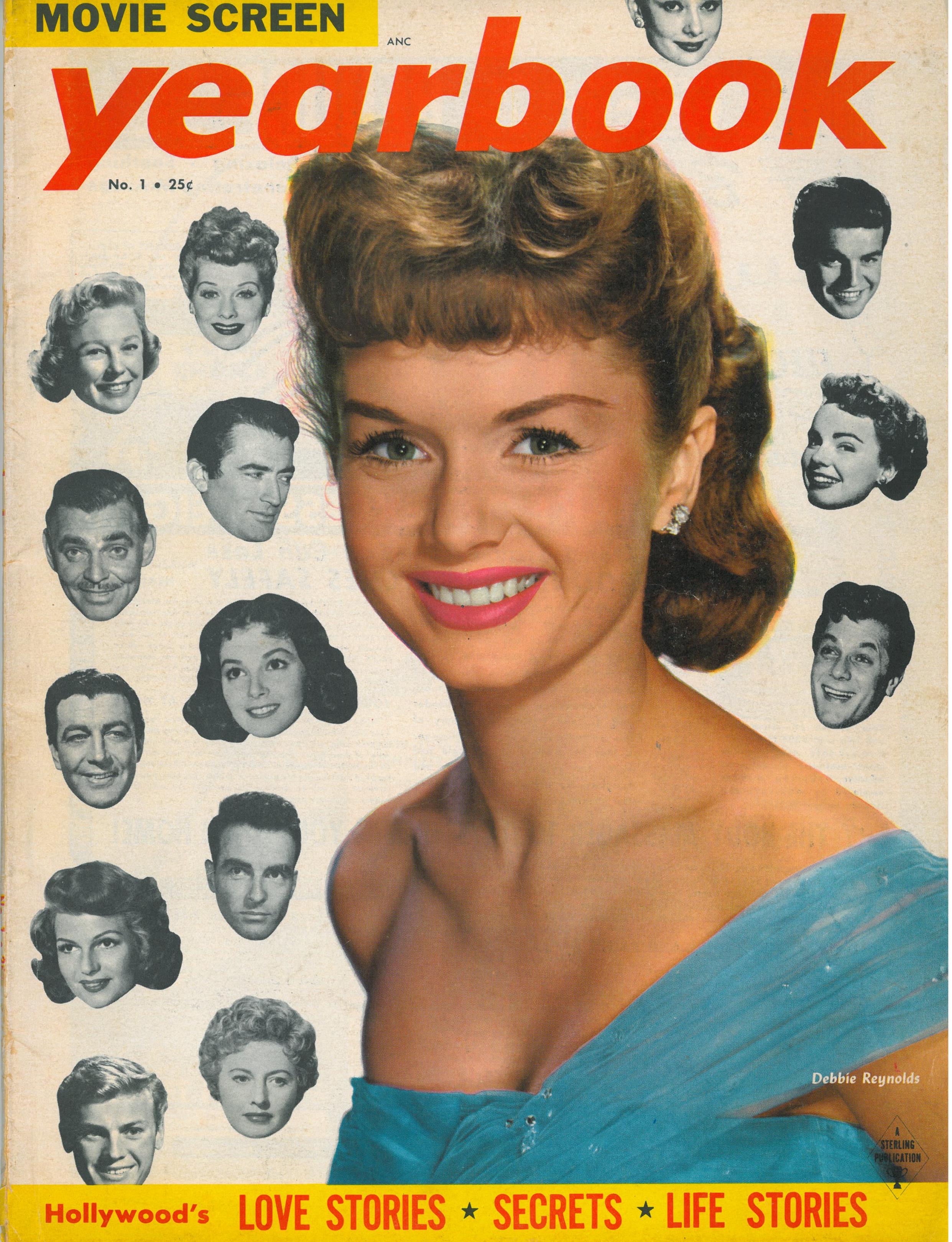

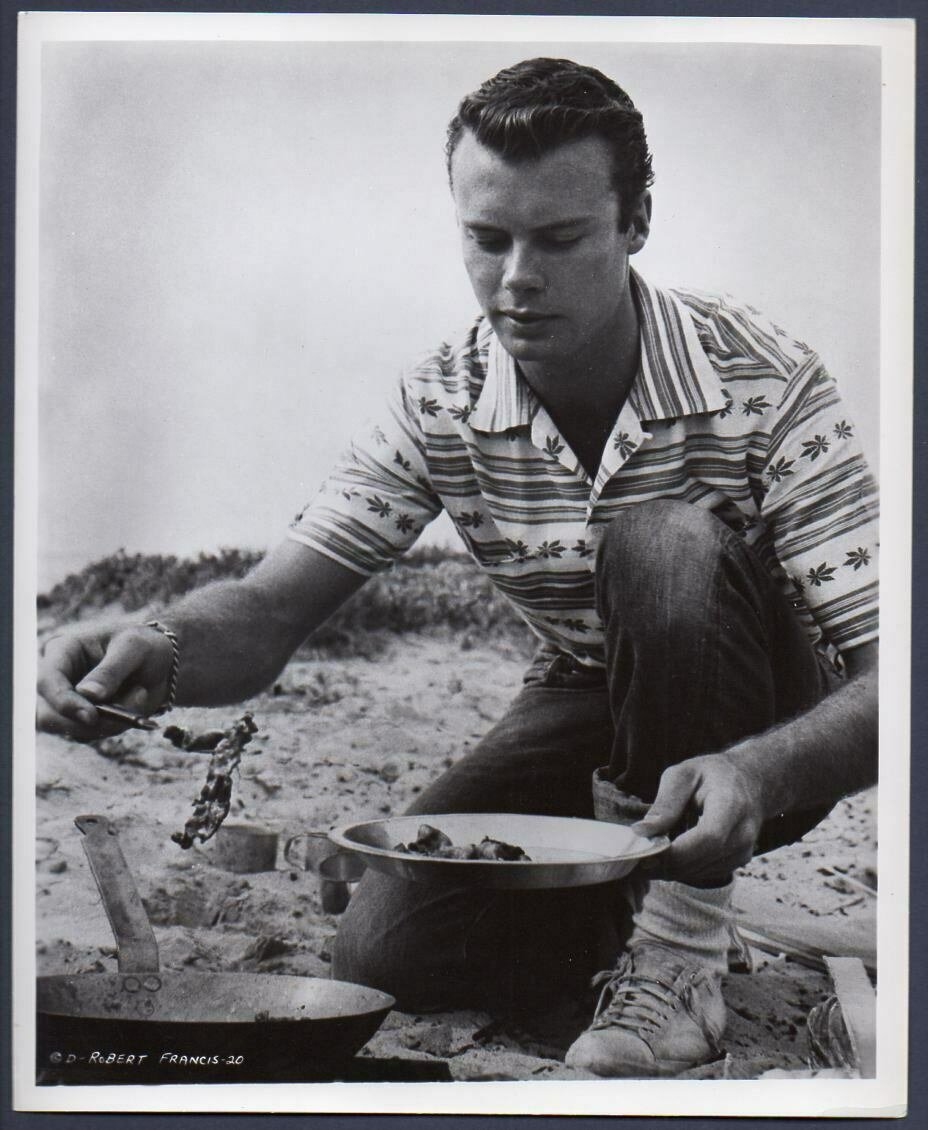

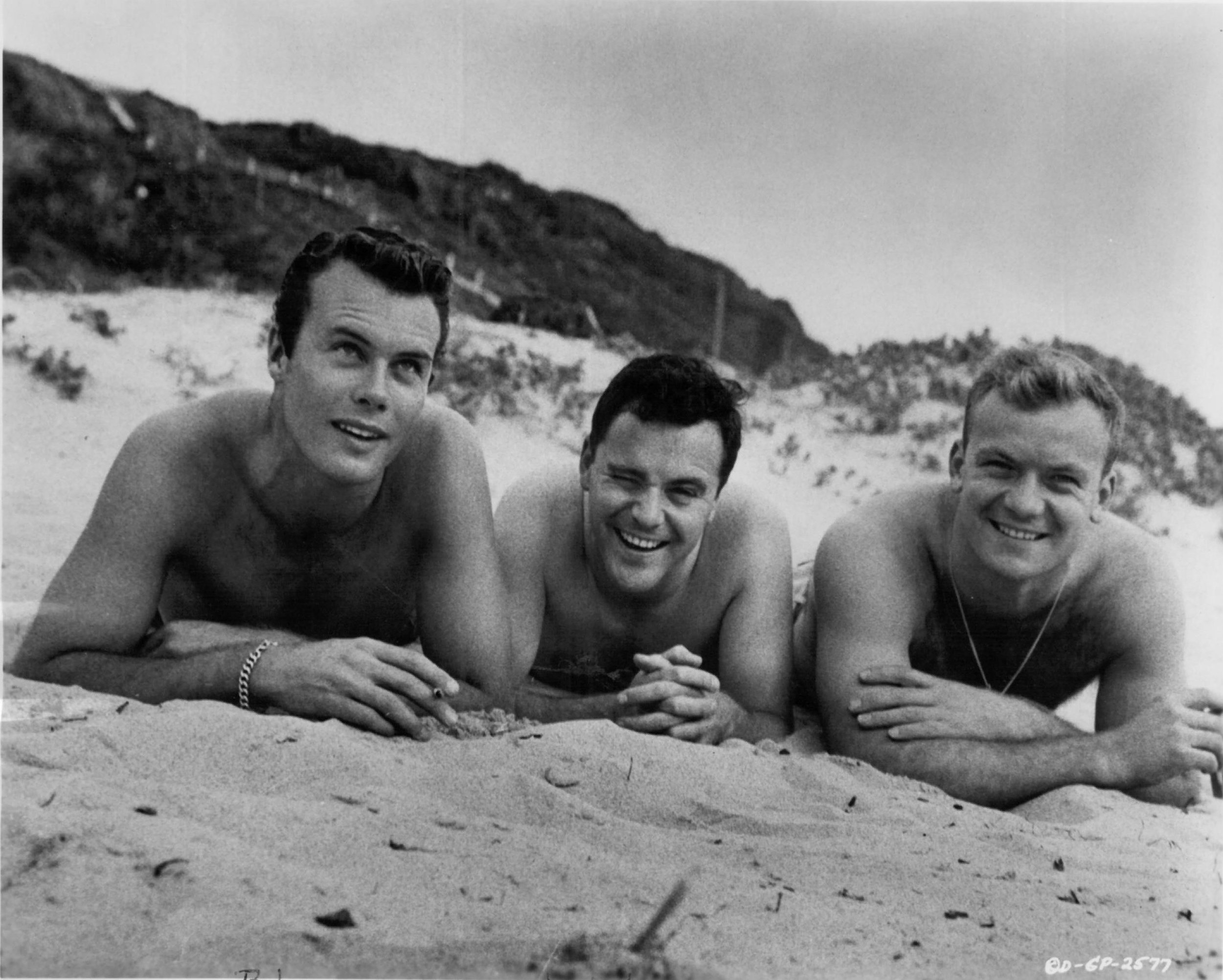

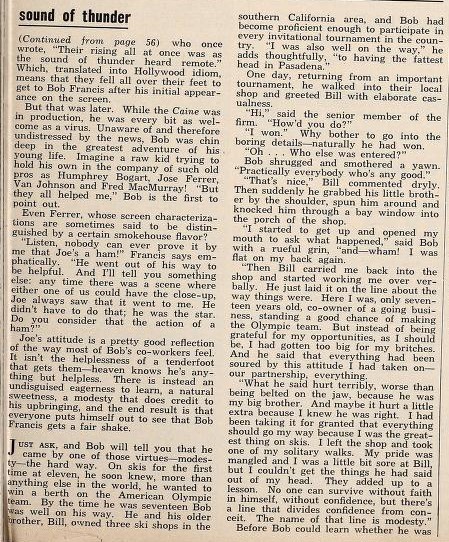

Movie Annual 1954, probably on newsstands in April or May 1954. Perhaps Bob’s first magazine cover. Note his image to the left of Debbie Reynold’s right eye. Photos taken Summer 1953. One of first photo stories featuring Bob and May Wynn, “It’s a Lovely Day Today.” Text references both The Caine Mutiny and They Road West, though neither was in release at time of publication. The issue also features an “outdoor guy” photo story on Aldo Ray. Bob’s “outdoor guy” photo appeared in Screen, Aug. 1954. Photos for both stories were taken Fall 1953; the shoot also included Jack Lemmon.

Early 1954

Note “Love Time” heading for the photo story with Bob and May Wynn. From this, came much of the interest in them and speculation about a romance. Both denied that at the time. May did likewise in recent years, too. Just publicity.

Bob had a photo session with Earl Leaf on or about June 5, 1954. The photos were made in Pasadena at home and in the Hollywood Hills near Leaf’s home. See Sidebars for more information about Leaf.

Summer 1954

Movie Screen Yearbook 1954 includes references to and photographs of Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio’s wedding in Jan. 1954 and Audrey Hepburn’s winning 0scar and Tony awards in Spring 1954.

Photo probably taken Fall 1953 (based on hair cut with curl for They Rode West). This jacket appears in many photographs, e.g., in “It’s a Lovely Day Today.” (above)

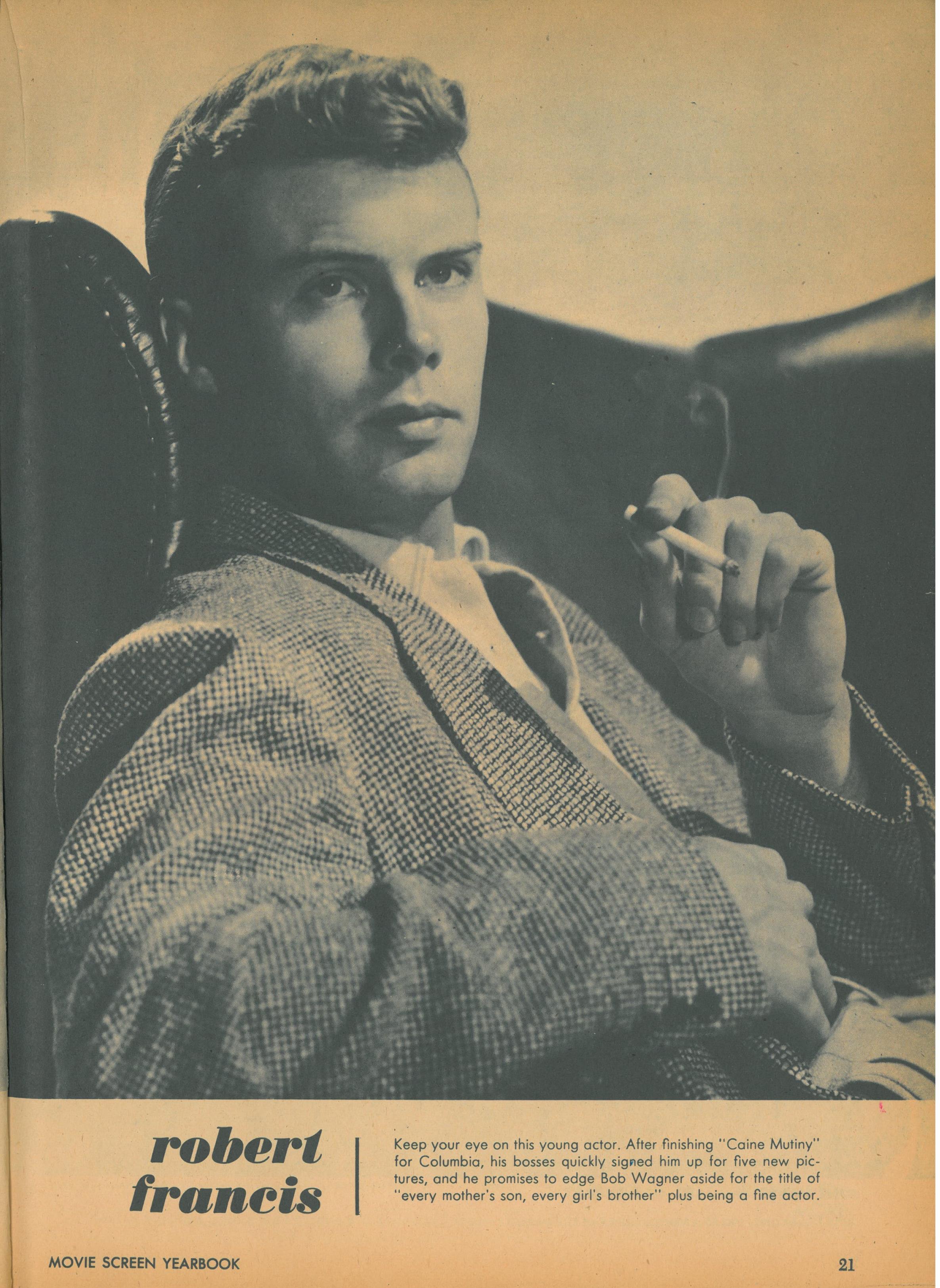

Hollywood Men No. 2, June 1954

Hollywood Men No. 2, June 1954. Photo made in Spring 1953.

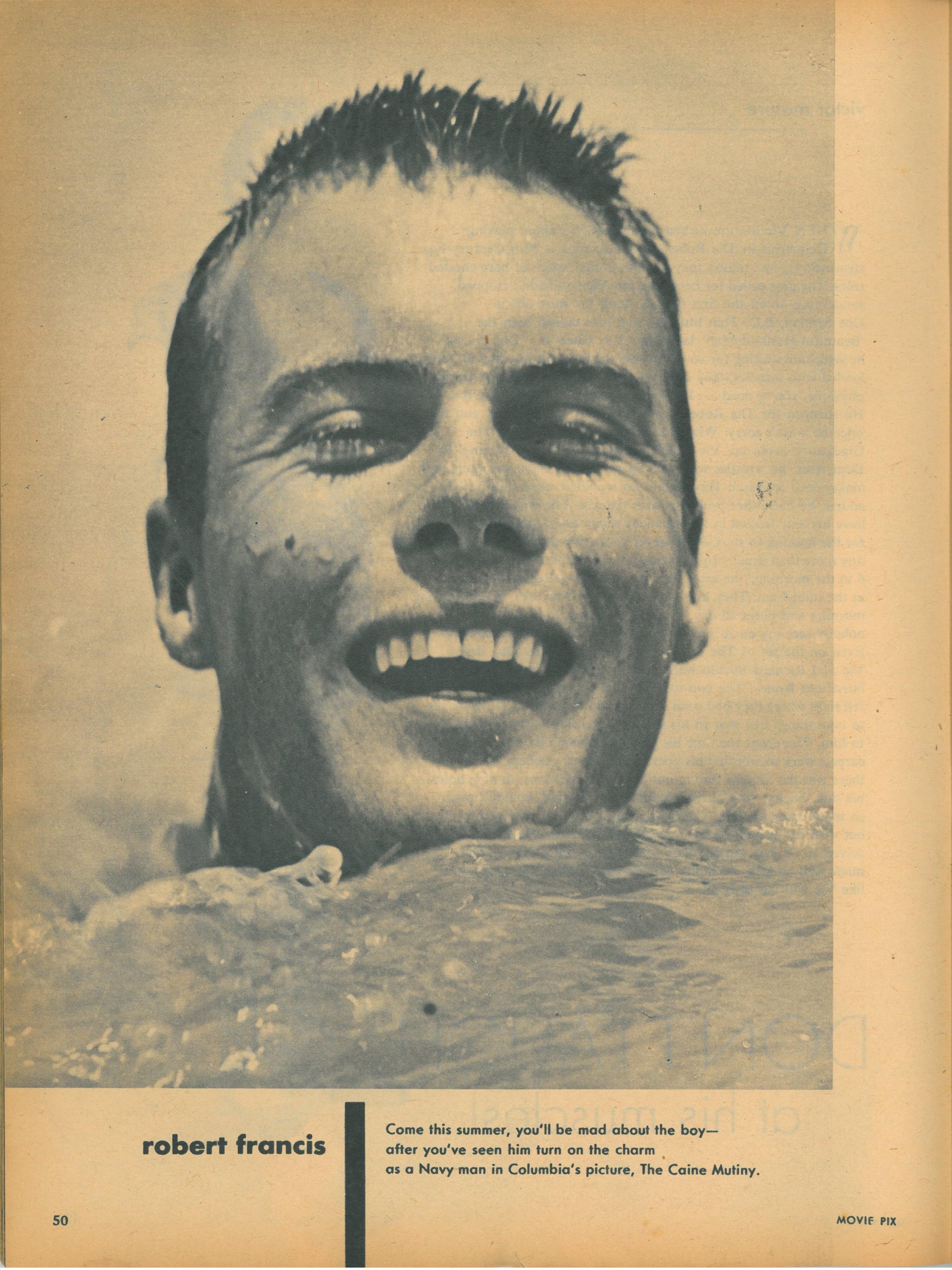

Movie Pix, June 1954, on newsstands in early May 1954. Photo of Bob made when on location in Hawaii, Summer 1953. Columbia Pictures photographer.

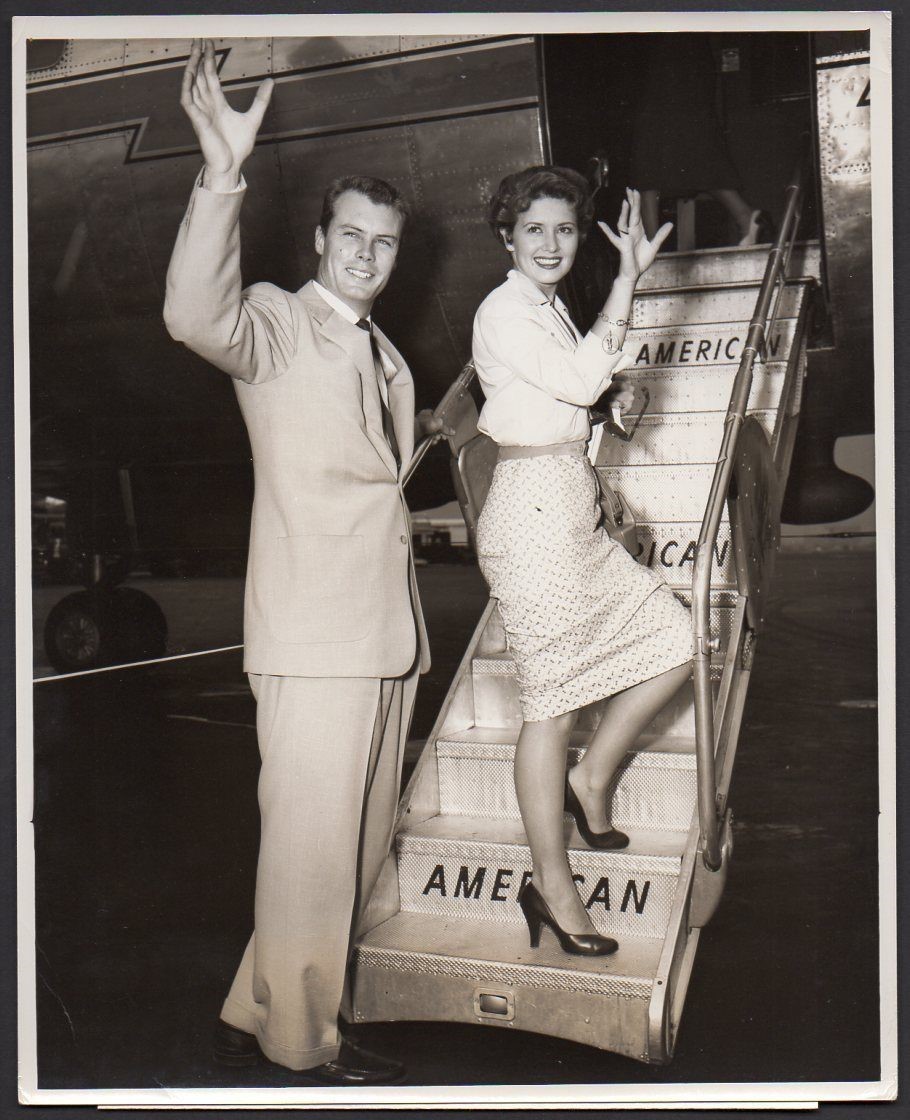

June 25, 1954

Bob and May Wynn boarding American Airlines plane from New York City to Boston for their The Caine Mutiny tour. Columbia Pictures may have had a promotional partnership with American Airlines as there are other photos of Bob and/or May on American. Slater, photographer for American Airlines. Bob’s crew cut is similar to his hairstyle in The Long Gray Line filmed earlier in the year.

Joe Hyams, Columbia Pictures, Publicity Department, New York City:

“Caine Mutiny was an important film and I was with Columbia in New York in the Publicity Department (1953).

“Bob and that picture was assigned to me. It may have been his first trip back East. I don’t know if he had ever been to New York. It would have been prior to the release date of The Caine Mutiny. The other actors [Bogart, Ferrer, Johnson, MacMurray], you were not going to get on the road.

”I worked with Kim Novak and Jack Lemmon, because there were one or two of us (in publicity department in New York) who were the ‘Star Handlers.’ We would get them scheduled for press and interviews. Including Bob, they all had a terrific time in New York. They worked for a monster studio and that monster boss. They worked for Harry Cohn. They were owned by these guys. They came to New York and were living at suites at The Plaza Hotel. None of them had homes at their age. That’s when I would get in trouble. The bills with caviar listed would get back to the studio. They never had caviar in their lives.”

Source: Joe Hyams, interview, Aug. 11, 1992

![Radio Interview by Tod Williams with Robert Francis, Providence, R.I., Tuesday, July 13, 1954 (Transcribed by DW) [Station unknown, perhaps WHIM.] TW - One of the most exciting pictures of the year is going to open Saturday at the Strand Theater in](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cae1b78fb18204c84880832/1563995060466-1QSXQSGVAXRD96KZI145/BFbobmaylga+%283%29+back+6-25-54.jpg)

Radio Interview by Tod Williams with Robert Francis, Providence, R.I., Tuesday, July 13, 1954 (Transcribed by DW) [Station unknown, perhaps WHIM.]

TW - One of the most exciting pictures of the year is going to open Saturday at the Strand Theater in Providence. It is The Caine Mutiny and the main character in the book is Willie Keith. This morning we are fortunate to have with us Mr. Robert Francis who plays the role of Willie Keith in the picture. Bob, yours is a Cinderella career, isn’t it?

RF – A little bit actually when it comes down to it. I was very fortunate to be given a break that people wait for years to find.

TW – Now, how did you start? You and your brother were in some other kind of business, weren’t you?

RF – That’s right. From 1946 to 1949 we ran a ski business. I had a few years of college when I was 16 and I had always wanted to get into the ski business. I started skiing when I was 11.

TW – Skiing in Southern California — now wait a minute, Bob.

RF – It does sound funny, though we do have snow and mountains. We had two shops in the mountains and one in Pasadena. We had those for three years and suddenly in 1949, we had to terminate the business because we ran out of snow one year. When you are in a seasonal business, it can be very unhealthy if you don’t make some money. So, as a matter of fact, that date was July 4th that year — a day that kind of changed my life. Someone saw me on the beach from a studio.

TW – Which studio was that? Columbia?

RF – No, it was Universal at the time. And they called me the next day and said they traced the license on the car and wanted to talk to me. I thought it was very funny, but I was intrigued so I went out to see them. Well, in short order it became obvious to both of us that I was in no condition to work at that time, because I had no background. But they were interested enough that they sent me to a woman Botomi Schneider. And I worked with a group — Botomi Schneider’s Drama Workshop — in Hollywood at night and I worked with Botomi for a month. And she said, if I was sincere, I should keep working with her, and she felt that in due time something could be done. I felt that by this time, it was kind of a challenge and I should stick it out. So, I listened to Botomi and I didn’t go near anyone and I didn’t see anyone for a year. In 1950 her husband, Benno, took me to Columbia. At the same time I was kind of offered a contract without options from the Army.

TW – (laughter) Oh yeah, for how long?

RF - It was for two years and I came out February of last year [1953] and signed a term deal with Columbia pictures. [An unclear reference to his contract, perhaps a new contract for the standard seven years.]

TW – I think that’s kind of cute. You were a sergeant, weren’t you?

RF – I was a corporal.

TW - You exchanged your corporal’s stripes for a Navy uniform, and then landed the starring role in The Caine Mutiny. Did you get a bit of a sinking feeling when you found out you were really going to play Willie?

RF – Yes. It’s kind of a sensation you cannot describe because things happen so fast and the realization this would be one of the biggest pictures of the year and my suddenly finding myself in the middle of it after having read the book in the service and not even knowing I would have anything to do with it. So actually the realization didn’t hit me until after we had finished the picture, and that was three-and-a- half wonderful months.

TW – Well, is there anyone in your family that has done any dramatic work that would lead you into that type of thing?

RF – That’s the surprising part of it. Actually, no one in my family has ever been associated with the theatrical world. I stepped out, away from the family and here we are in motion pictures.

TW – It’s a wonderful thing to get a chance like that when so many fine people just work their hearts out to try and just get into pictures and suddenly you are a star overnight.

RF – Well, that’s one of the things, too. I mentioned to you it makes you feel a little bit chagrined even if you got the breaks and so forth, you watch these very talented people — very good friends of mine — who worked for years, who just haven’t quit.

TW – How is this man Kramer? He has done so many wonderful things in pictures.

RF – Stanley Kramer is probably one of the finest men you could ever meet. He has a great belief and sincere interest in everything he does, and that’s why all his motion pictures — some are thought to be a little bit arty. I know Stanley cannot be ashamed of any picture he has ever made.

TW – Oh, absolutely every picture that has come out under the Kramer signature has been a marvelous picture. You know there is just one thing. You are an awfully big boy, aren’t you?

RF – Yes, a little bit. I am 6’ 3” and I weigh 194.

TW – That makes you wonder. You can do a lot of things in pictures. But in my reading of The Caine Mutiny, I always thought Willie was of medium height and sort of chubby?

RF – Well, that’s the way he was physically described in the book. But the casting of course — in the picture Stanley felt that things like that — physical necessity and so forth — were not necessary to portray this on the screen. That’s why in the case of Van Johnson’s character as Maryk — and everybody said I cannot see this man as Maryk — he does a great job — one of the finest performances he gives in his life.

TW – I have often heard that while Mr. Bogart is a marvelous actor, he is a little difficult to work with?

RF – Well, I didn’t find it as such, but, let me tell you, he’s got a great bark, but this man’s premise in life is honesty. He is one of the most honest guys you can meet, and accepts his job as a profession and approaches it this way. This is actually one of the few stories that comes along once every five or ten years where all of the characters are clearly defined, and you can actually sink your teeth in and do something with this part. A lot of them, you know as well as I do, that you go to pictures and some of the characters are actually wishy-washy. Well, every one of them here are clearly defined and these four people — Bogart, Jose Ferrer, Van Johnson, and Fred MacMurray — all of them just threw themselves into this thing and it is my feeling — of course I am biased working on this picture — but I think it is a fine film.

TW - Well, I don’t see how it could help but be because in his [Wouk] book every character is completely, clearly defined. I understand the Navy took a dim view of this, when it first started out.

RF – Well, the Navy — after reading the book, they were a little bit concerned about what would happen if this was put on the screen. Well, after talking to Stanley Kramer, he went to Washington and met with the Secretary of the Navy, and they finally accepted Stanley’s viewpoint on the motion picture, and realized that the film concerns just three or four men and how they meet the crises of their lives. This is, of course, defined in the picture — and now from the Navy’s standpoint it is nothing but an asset to the Navy.

TW – Well, now aside from The Caine Mutiny you have completed several other pictures, haven’t you?

RF – Yes, there have been three after Caine.

TW – I think I should tell our friends at home, Bob, that you remind me considerably of Van Johnson himself — but it is just about time we had another young handsome man come along. How does it feel to get the star treatment?

RF – Well, of course, as I say, this all came at once and I was thrown in the middle of this — it is something that I have not even had the chance in the last year to stop and think about it. I have made four pictures and now I am out on the road. And, all of this, of course, is wonderful to me. It is all new and exciting. By the same token, I am immersed in my work and I have been concentrating on that more than anything else.

TW – Well, there, friends, is Mr. Robert Francis. Well, I know you are going to see this because everybody within this whole area is going to go right over to the Strand Theater and see this marvelous picture The Caine Mutiny which is opening on Saturday the 17th [of July].

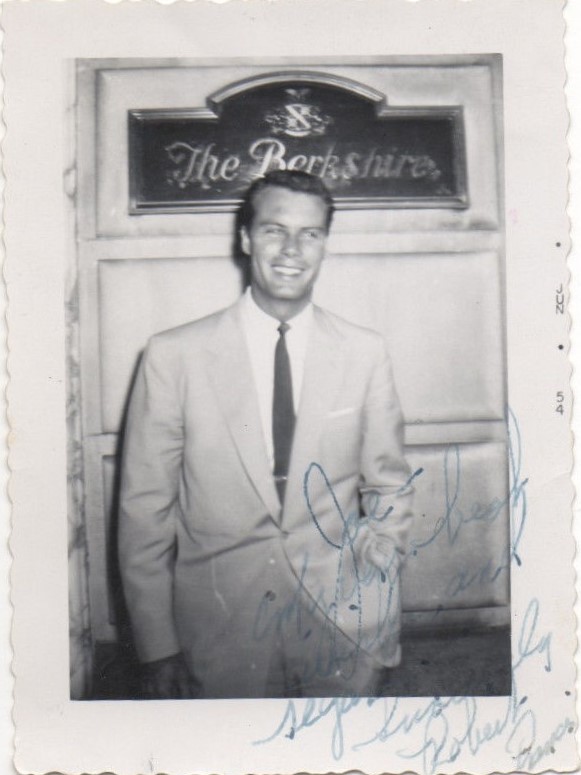

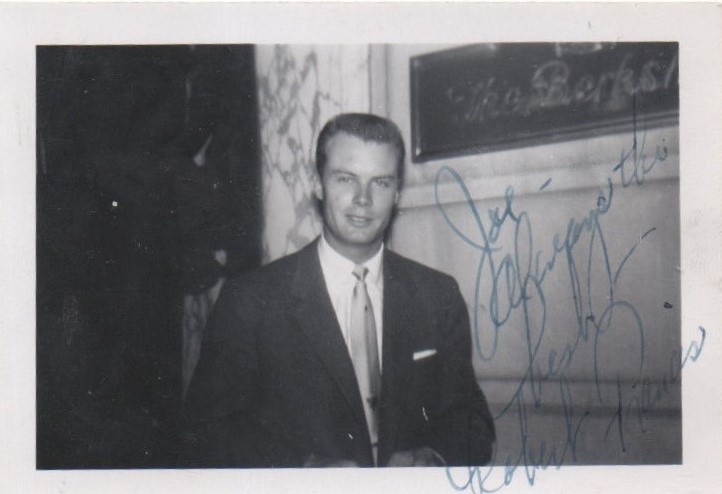

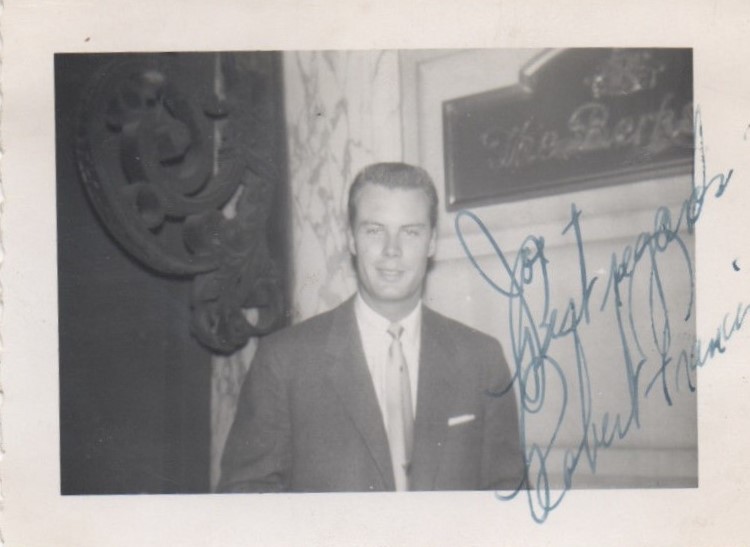

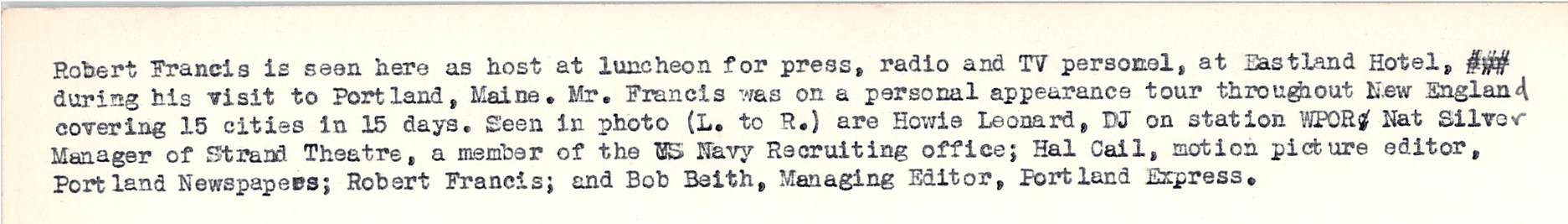

A candid photo by a fan is stamped JUN 54 indicating it was taken and/or developed that month, later sent to Bob to autograph to “Joe,” and then returned to Joe. The Bershire is believed to be (or to have been) a New England hotel where Bob stayed during a personal appearance tour. Bob was in Boston briefly in late June 1954; he also had a 15-day New England tour in Dec. 1954. The suit he is wearing in the above photo seems to be the same one he is wearing in the American Airlines photo with May Wynn. Two similar photos autographed to “Joe” probably were taken in June 1954, also, based on Bob’s haircut.

“Bob was good (on promotional tours). I remember having a very pleasant time with him and getting a lot of work done. He was a very agreeable type of guy.

“They (Bob and May Wynn) were good friends, because they both went through that studio system together. We called her May, but her name was Donna. I remember picking her up in Forest Hills. She was staying with her mother who was just down the street from my house. Her mother would come to screenings in New York and ask how May was.”

Source: Joe Hyams, interview, Aug. 11, 1992

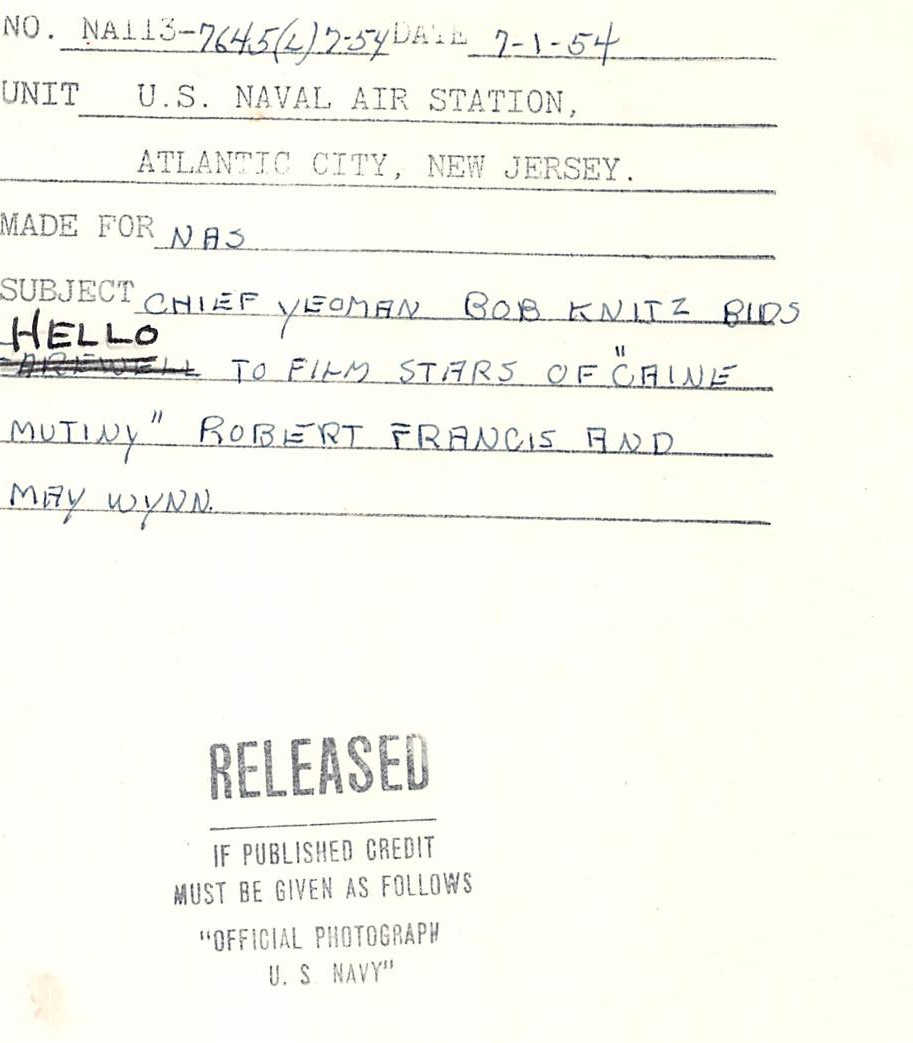

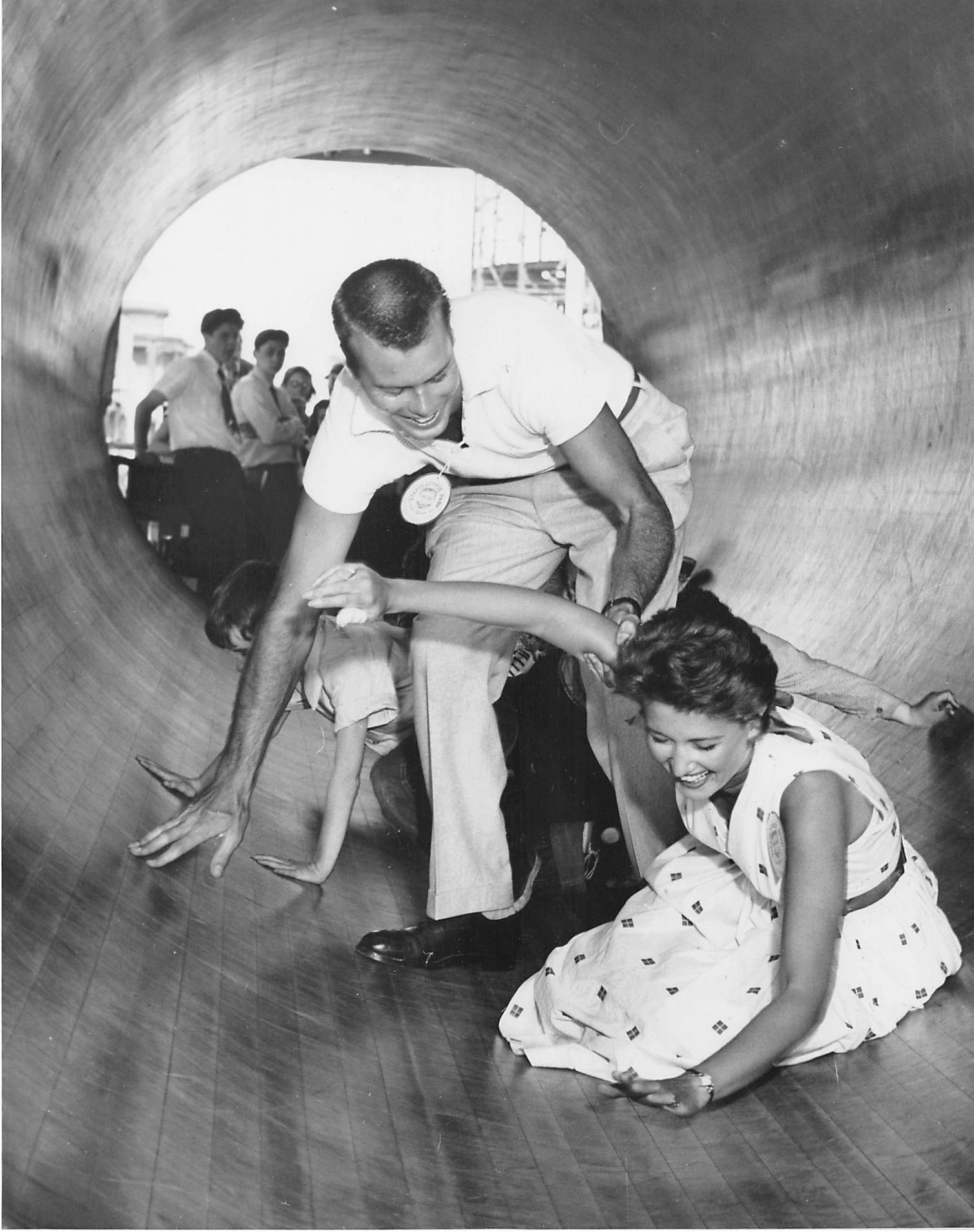

Below: Bob and May Wynn promoted The Caine Mutiny in July and Aug. 1954. These photographs were taken at Atlantic City, N.J., where Steeplechase Pier had a roller coaster, a monorail that stretched out over the ocean, and numerous other fun and exciting rides. The Steel Pier was known as The Funny Place.

They were made honorary citizens of New Orleans, c. July 9, 1954.

July 1954 - The beginning of the deluge of fan magazine articles and photo stories — all carefully created and placed by Columbia’s publicity department.

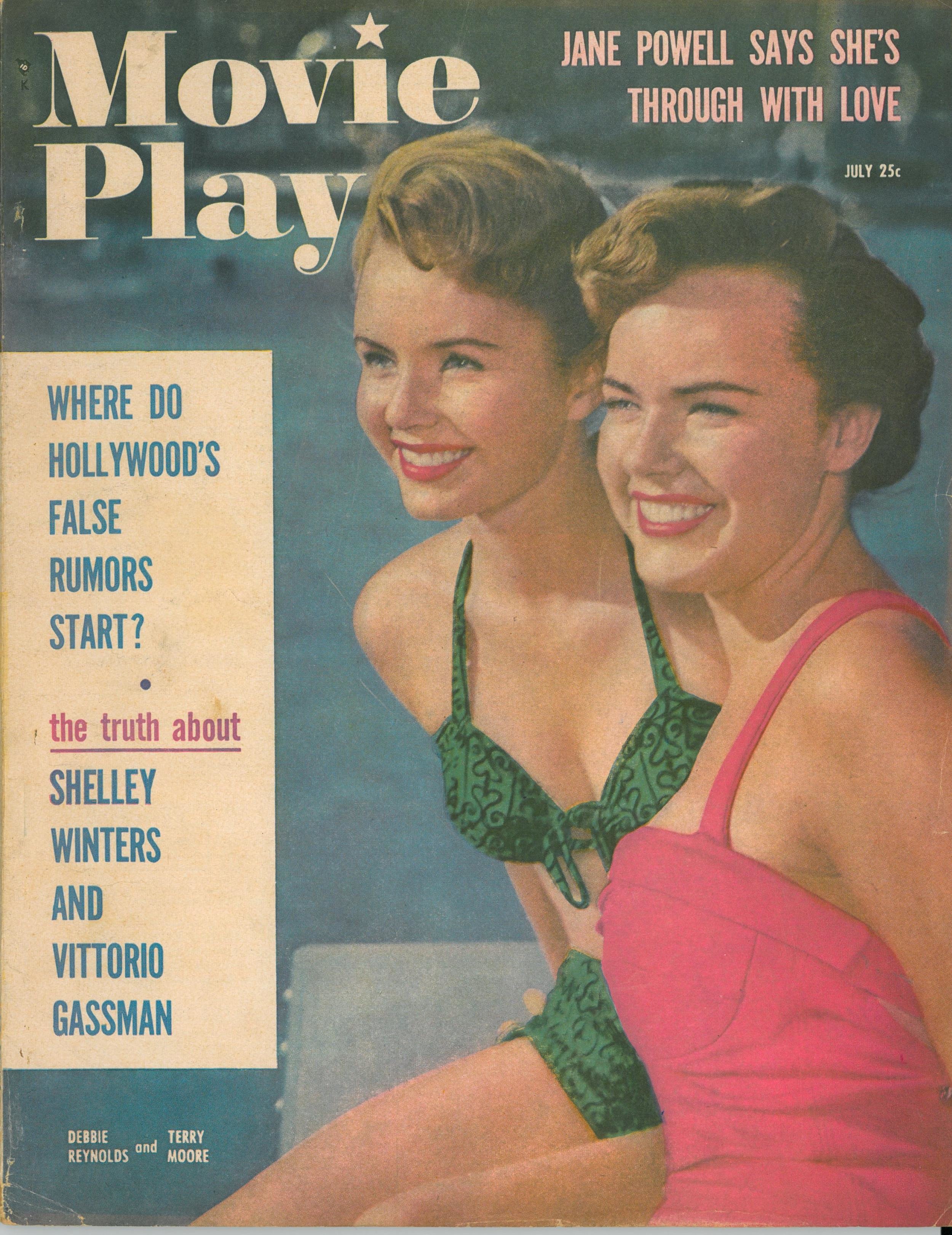

Movie Play, July 1954, on newsstands in early June 1954. Photo of Bob in They Road West costume taken Fall 1953. Columbia Pictures photographer. Bob holds this issue in a photo taken by Earl Leaf on or around June 5, 1954 (see above).

July 24, 1954

Salt Lake City was one stop on Bob’s two-months, 19 cities “transcontinental publicity slalom” personal appearance tour to promote The Caine Mutiny.. He usually appeared prior to the opening date for the film and did advance phone interviews with press members, as well as one-on-one interviews in each city.

The Pasadena Independent, Aug. 12, 1954. “Just for Girls” by Jackie Russell was written from a one-on-one interview with Bob at his parents’ home in Pasadena. His mother, Lillian, makes an appearance; he was “Bobby” in the family circle. Dorothy Ross is mentioned as is his new Cadillac, acquired when he was on tour earlier in 1954, and his search for an apartment of his own. Columbia Pictures photo taken Spring/Summer 1953.

After Bob’s death, his parents wanted to keep his 1955 Coupe De Ville Cadillac. It was cream colored with gold upholstery. They had no space for it in Pasadena. Bob’s brother Bill took it to Bisbee, Ariz., where he was living. Eventually, he sold it to a man from Canada.

Source: Bill Francis, interview, Aug. 1992.

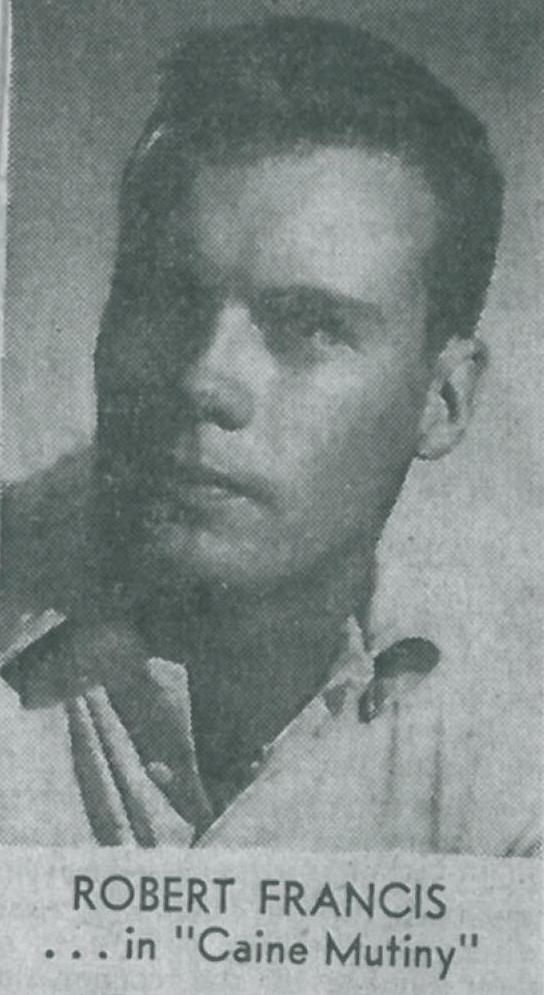

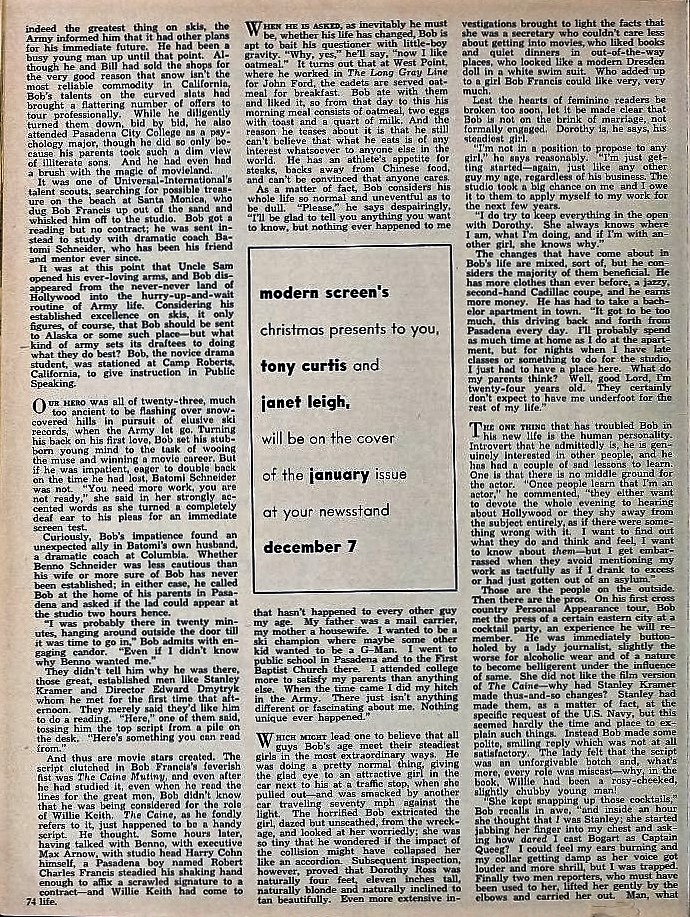

Movies, Aug. 1954, was on newsstands in early July 1954. Most of the photographs for this story were taken a year earlier, Summer 1953.

Bob purchased a new Cadillac in 1954 to replace his Lincoln. There is a reference to his being “a competent pianist” and organ player. The Hawaiian shirt appears in other photographs, as does the shirt with horizontal elements.

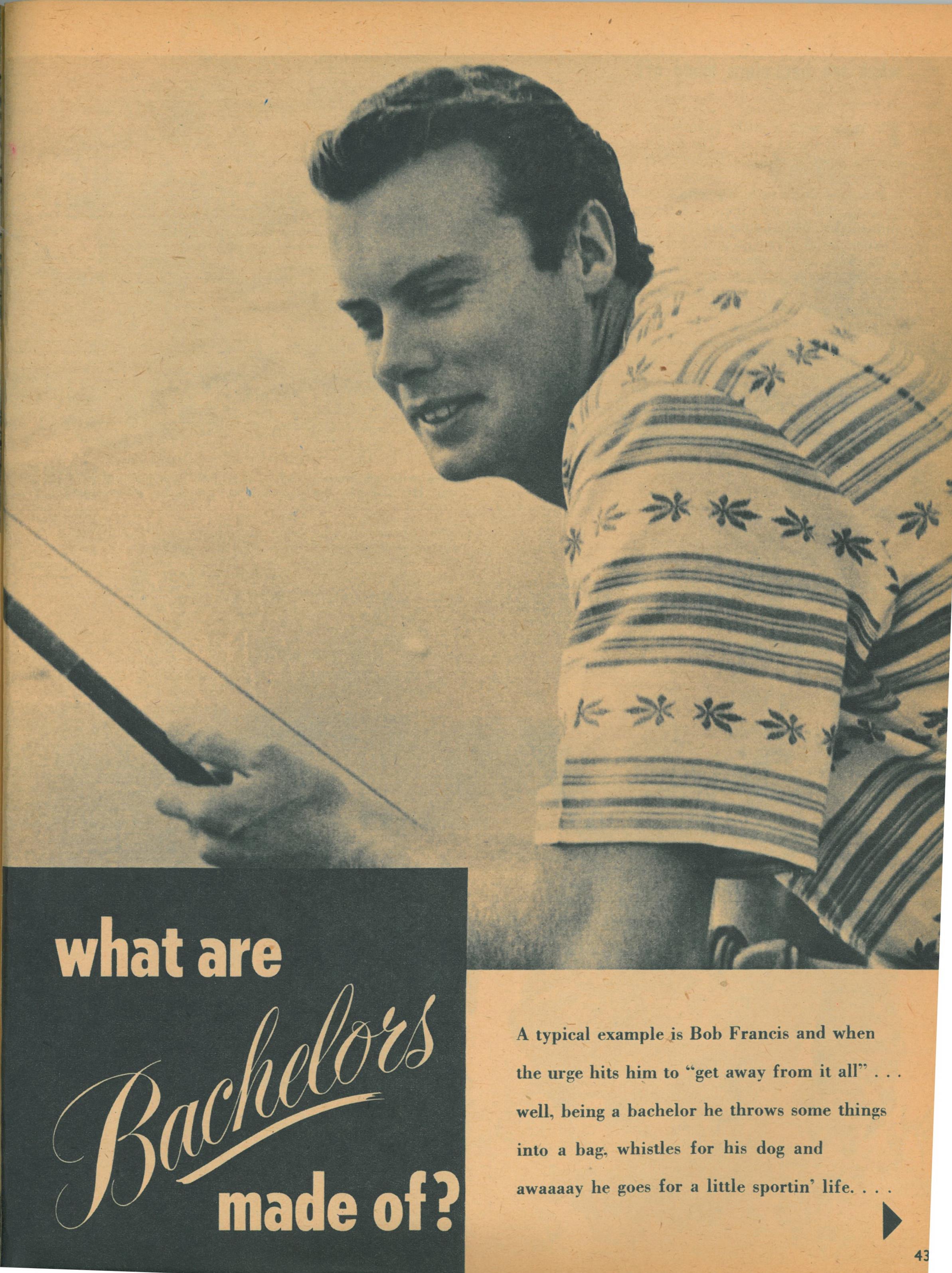

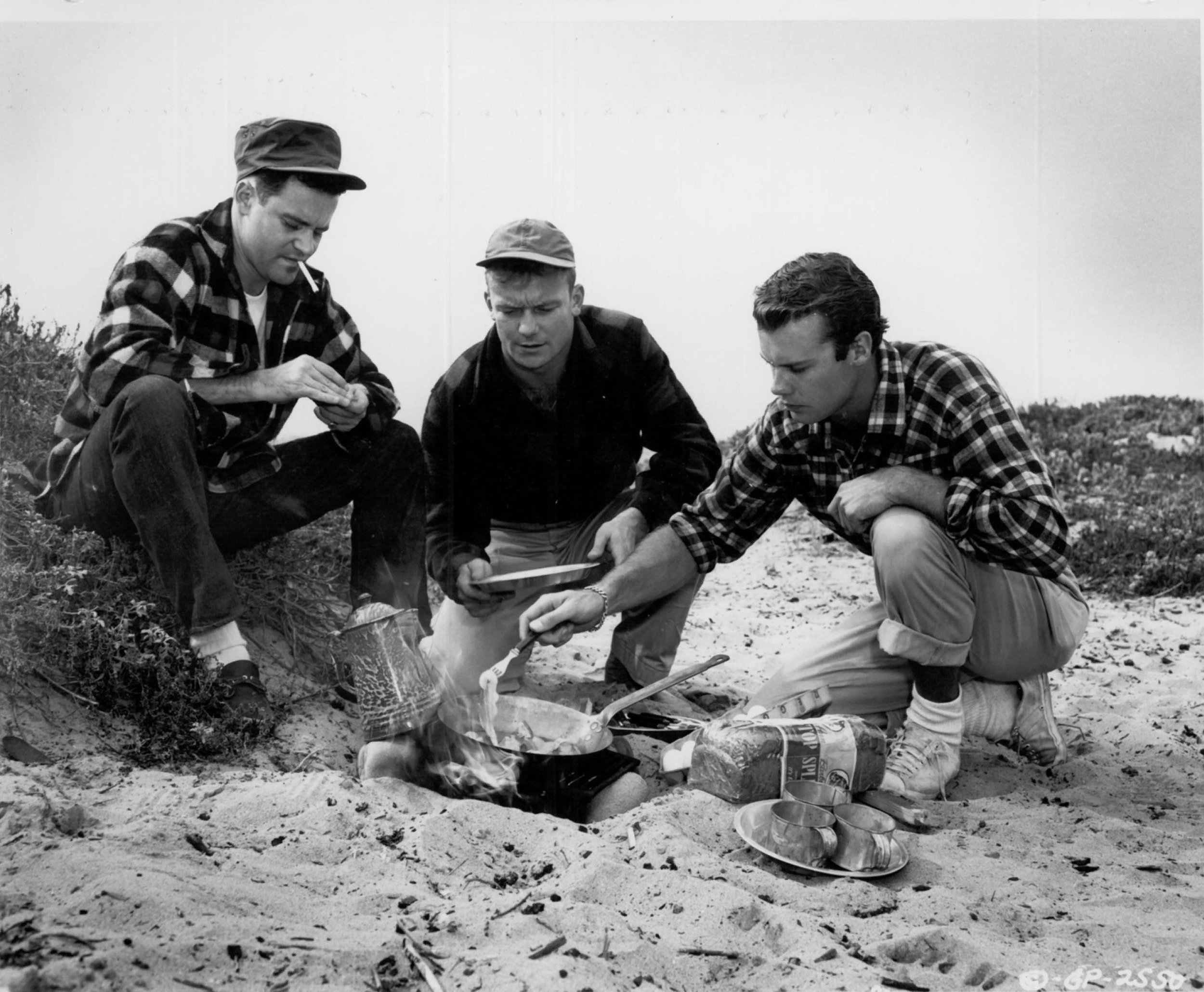

Screen, Aug. 1954. Photos taken Fall 1953. Several of the photos will appear in other “outdoor” photo stories including one with Columbia contract players Jack Lemmon and Aldo Ray.

Below: Screen World, Aug. 1954, on newsstands in early July 1954, includes reprint of “It’s a Lovely Day Today” photo story from Movie Annual (see above) from earlier in 1954. It also includes Aldo Ray’s “version” of the hunting/swimming/dog story that appeared in Screen, Aug. 1954. (See above.) Photos for both stories probably taken at the same time, Fall 1953. See photos of Bob, Ray, and Jack Lemmon. A photo story featuring all three or just Lemmon may have been published.

“Bob in particular I had a deep affection for. He was a very sweet guy. I remember he worked very hard. He was very personable. People liked him. No problems at all. Jack (Lemmon) was much more sophisticated. He came from back East. You know, he knew New York.”

Source: Joe Hyams, interview, Aug. 11, 1992.

An outtake from the photo shoot.

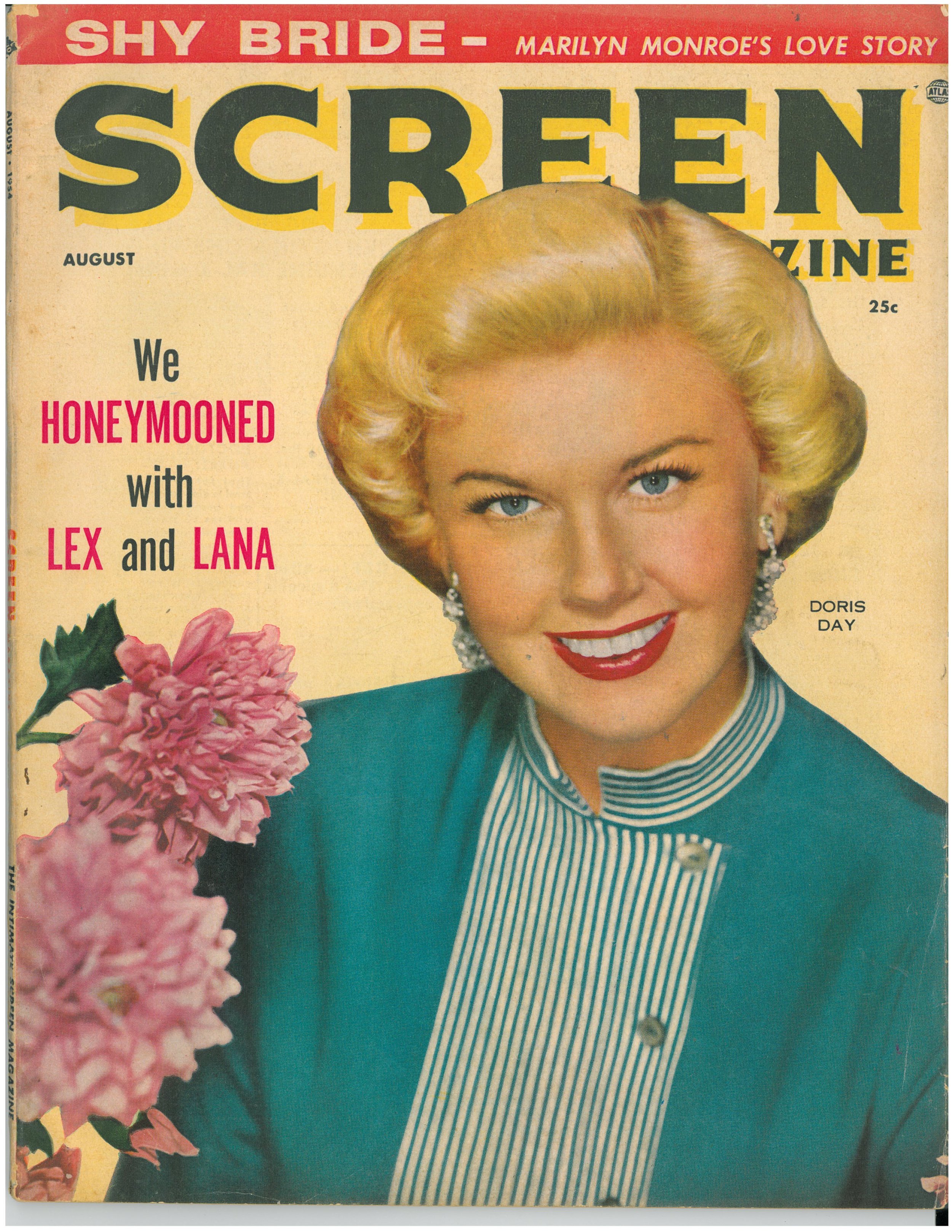

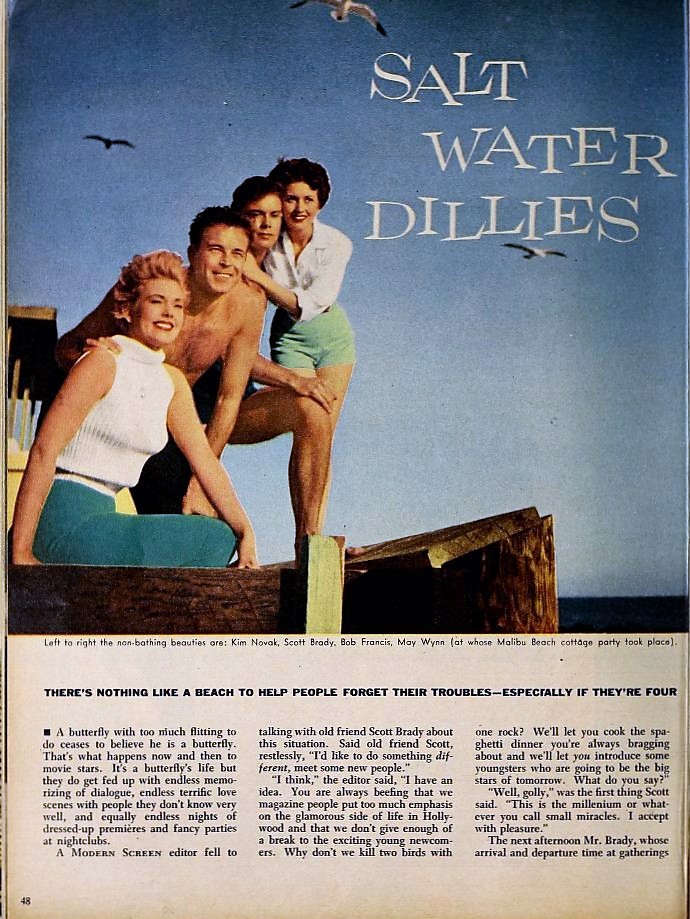

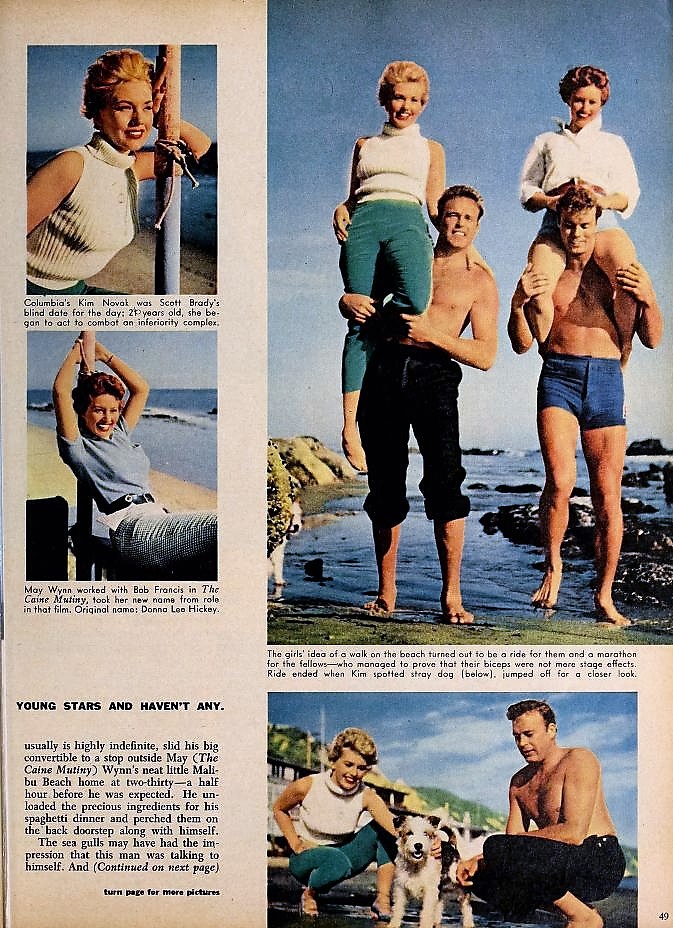

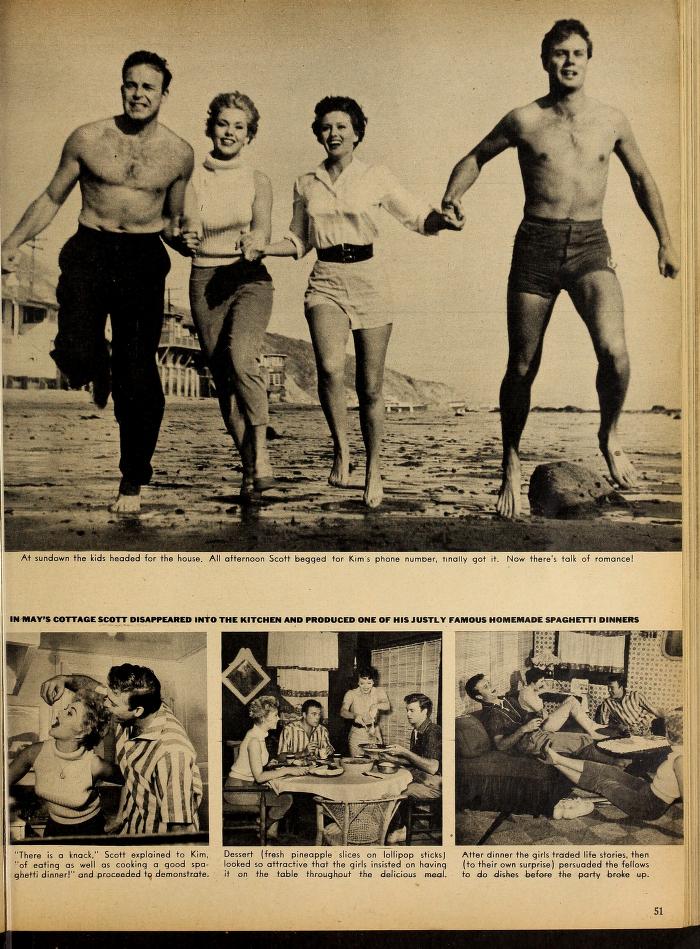

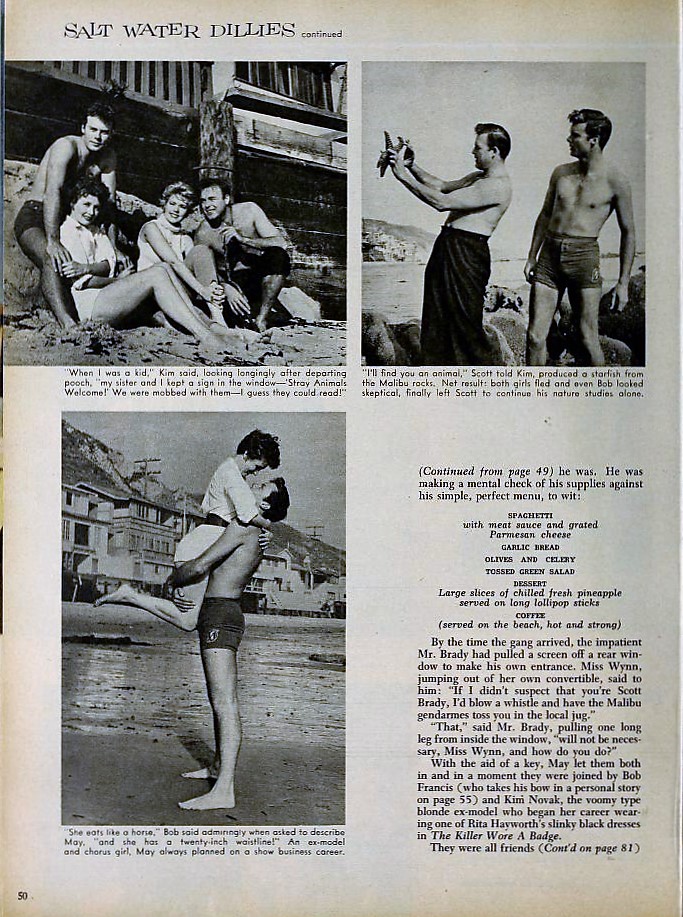

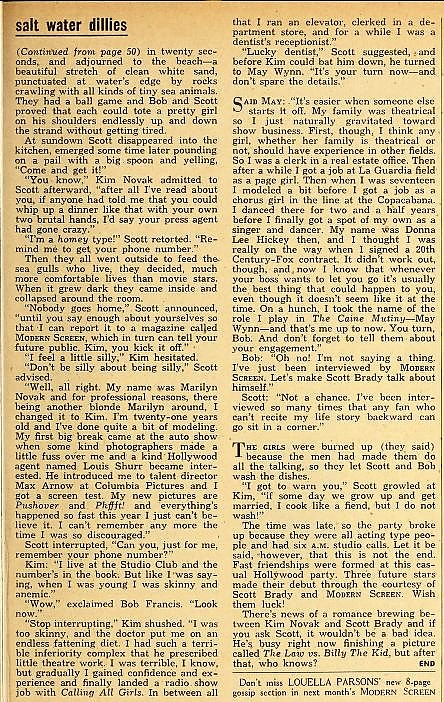

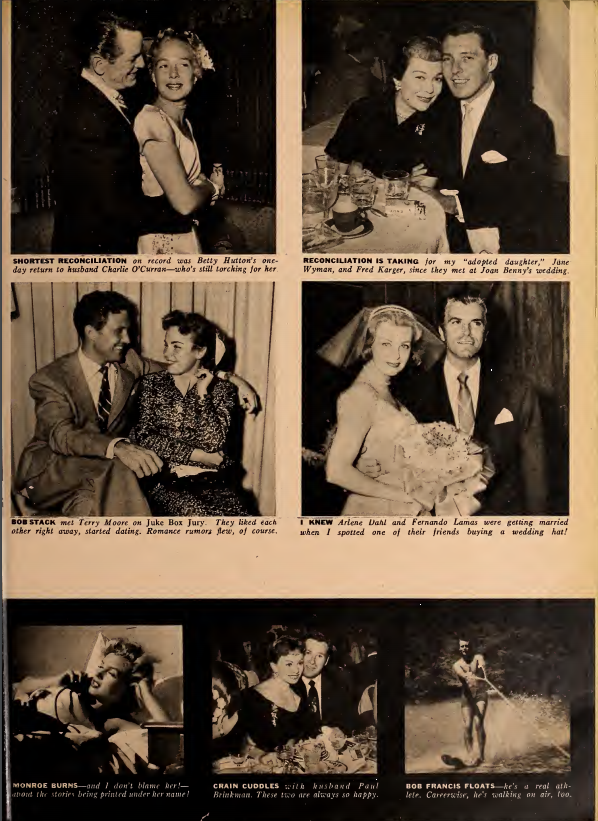

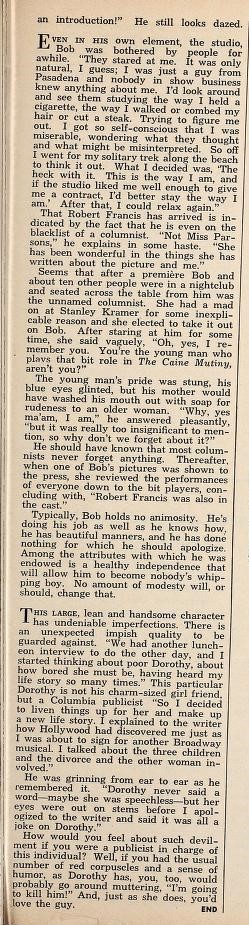

The Aug. 1954 issue of Modern Screen featured two Bob Francis stories: The long biographically oriented story (reprinted in full in this section, above) and “Salt Water Dillies” which may have been photographed in Fall 1953. Scott Brady appeared in a number of films released by Columbia and may have been under contract there; he also often appeared in films released by Universal-International and other studios. Novak and May were, like Bob, Columbia contract players. The issue also contained a ballot for the annual awards for favorite stars and top new stars of 1954. Bob won the “new star” award, along with Grace Kelly.

“Kim (Novak) was kind of guarded. The guys (on personal appearance tours) did much more work. You don’t have to sleep at that age. You go out and party all night. They all looked good. They didn’t have to worry about their looks.”

Source: Joe Hyams, interview, Aug. 11, 1992.

Modern Screen, Aug. 1954 (Complete story above.)

Above: Modern Screen, Aug. 1954

Below: Modern Screen, Sept. 1954. Photo (below) made in 1953; it appears in several different issues of fan magazines.

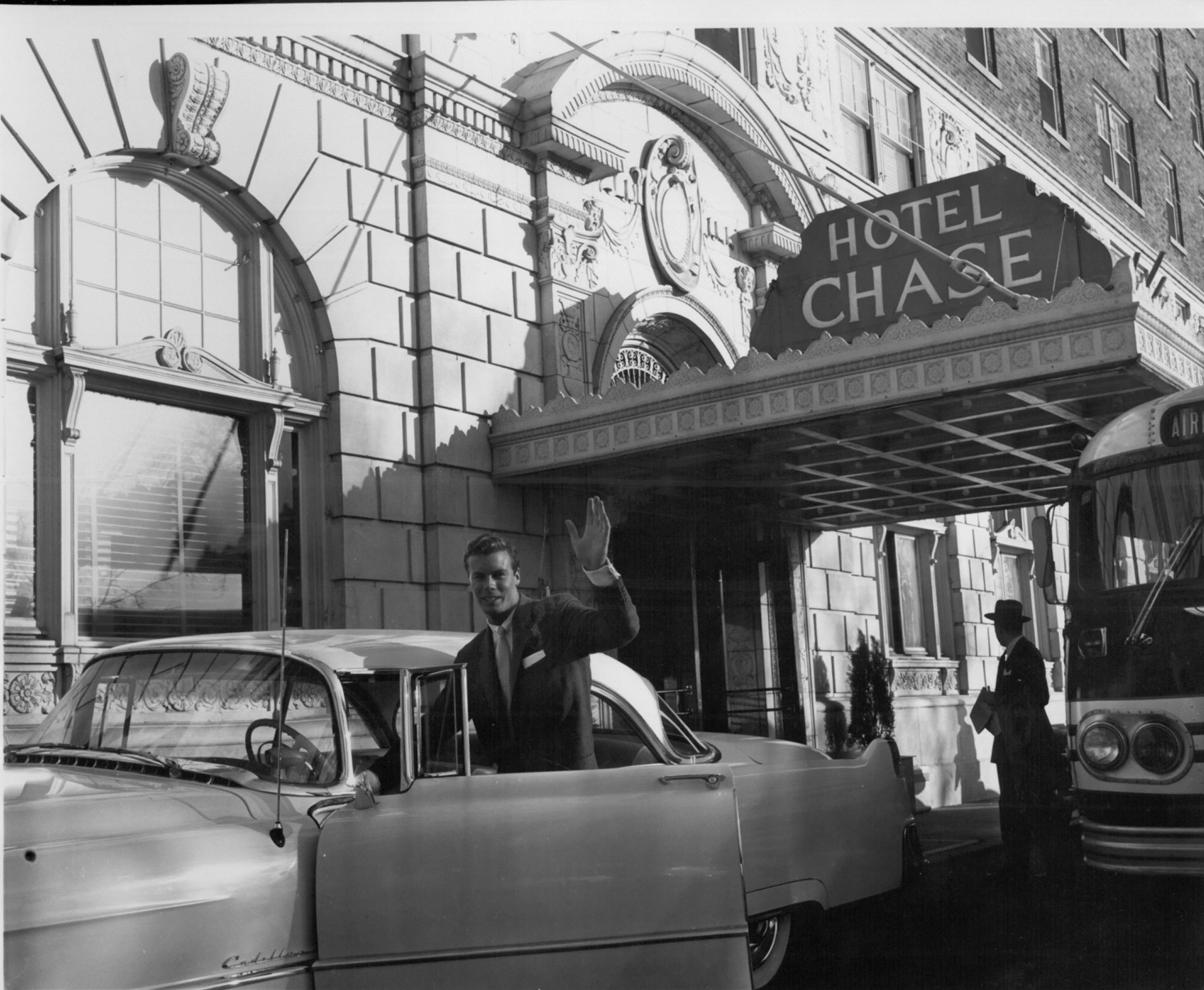

One of Bob’s tours in 1954 took him to St. Louis, Mo., where he stayed at the Chase Hotel in the Central West End section of the city, among other cities. On the tour he purchased a Cadillac (probably in Detroit) which he then drove to many of the tour cities, including Phoenix in early Aug.

Sept. 19, 1954

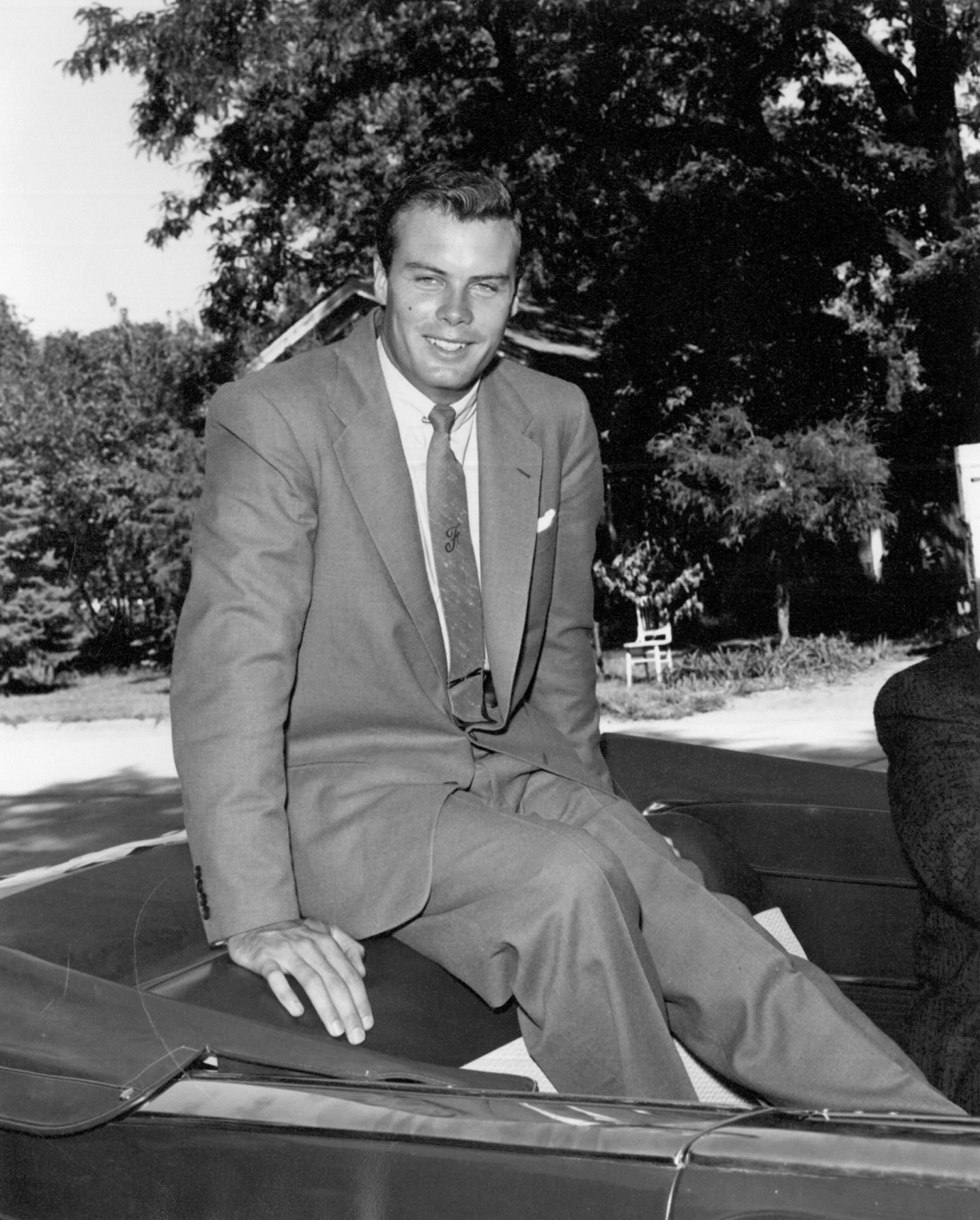

Bob’s fall tour to promote The Caine Mutiny and They Rode West included a stop in Bellevue, Neb., where he had Francis and Warnock relatives. (See Biography section.) He participated in a parade and was photographed by Bennie Anderson Studios. Bob’s “F” tie appears in several other photographs.

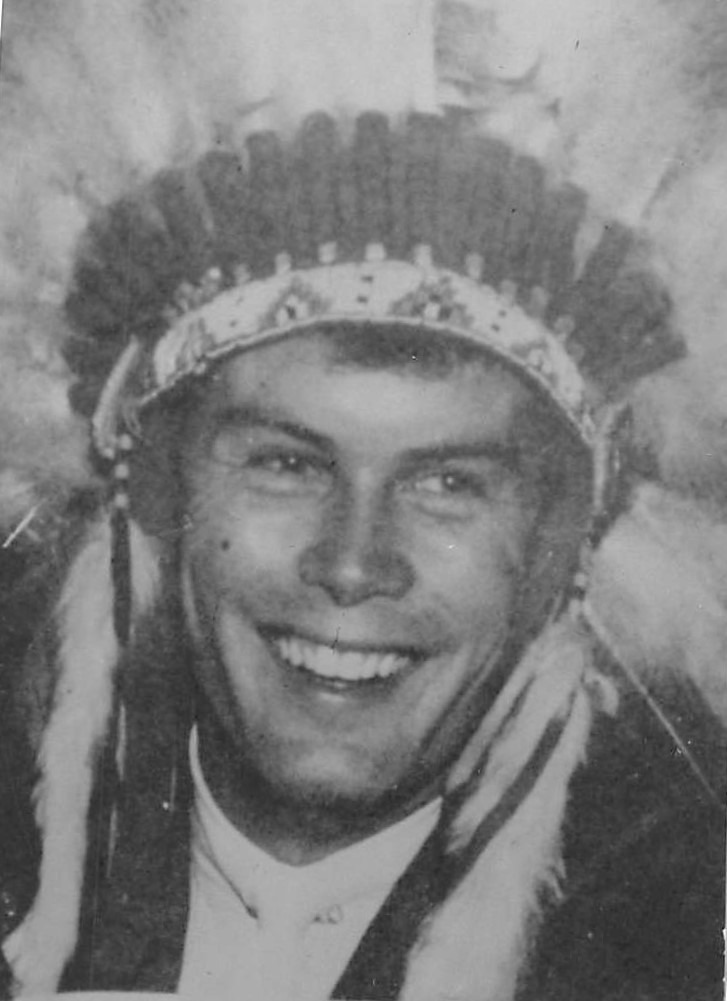

Below: While in Neb., Bob participated in an event in which he wore a “traditional” Native American headdress.

Fall 1954

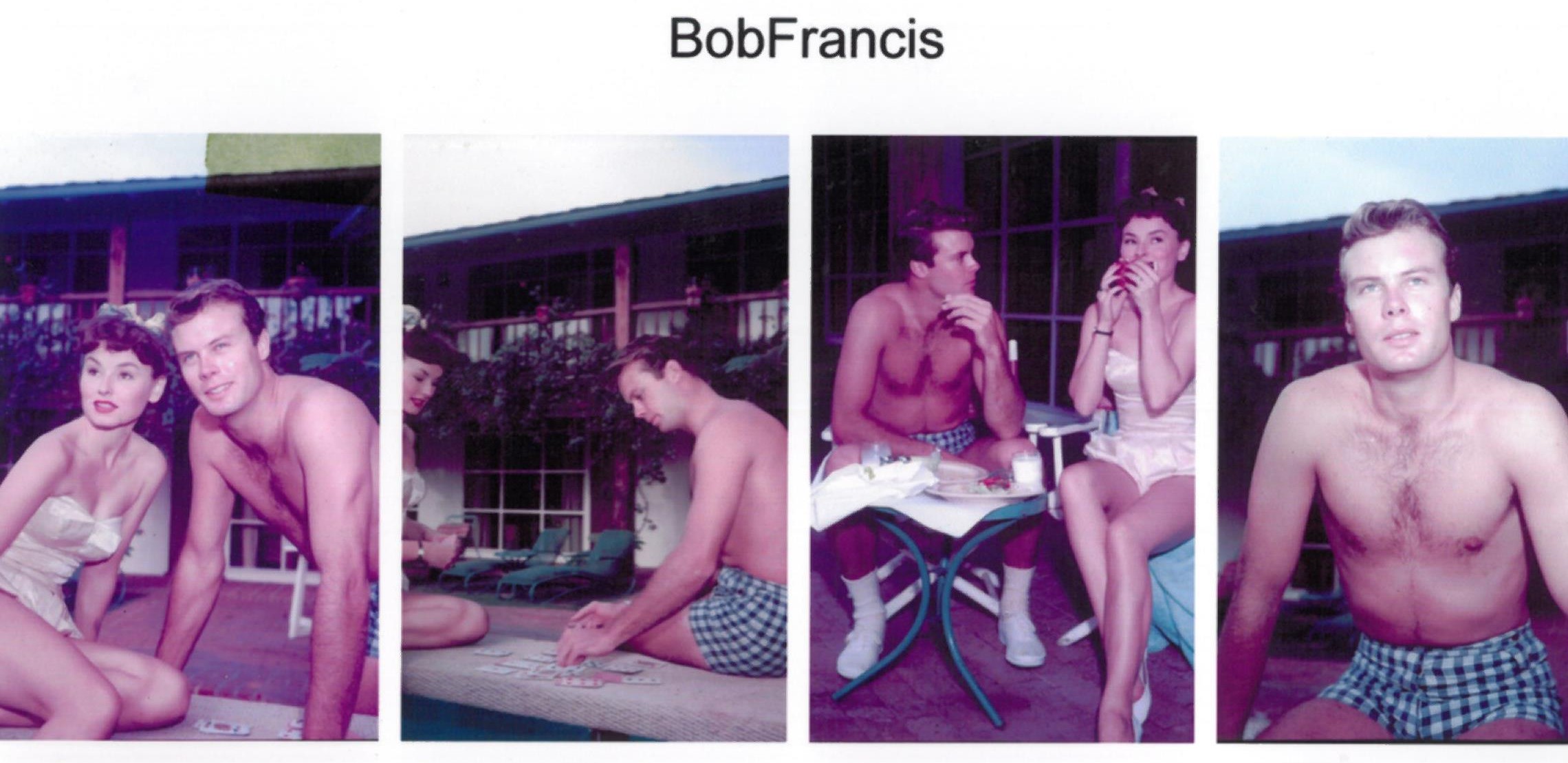

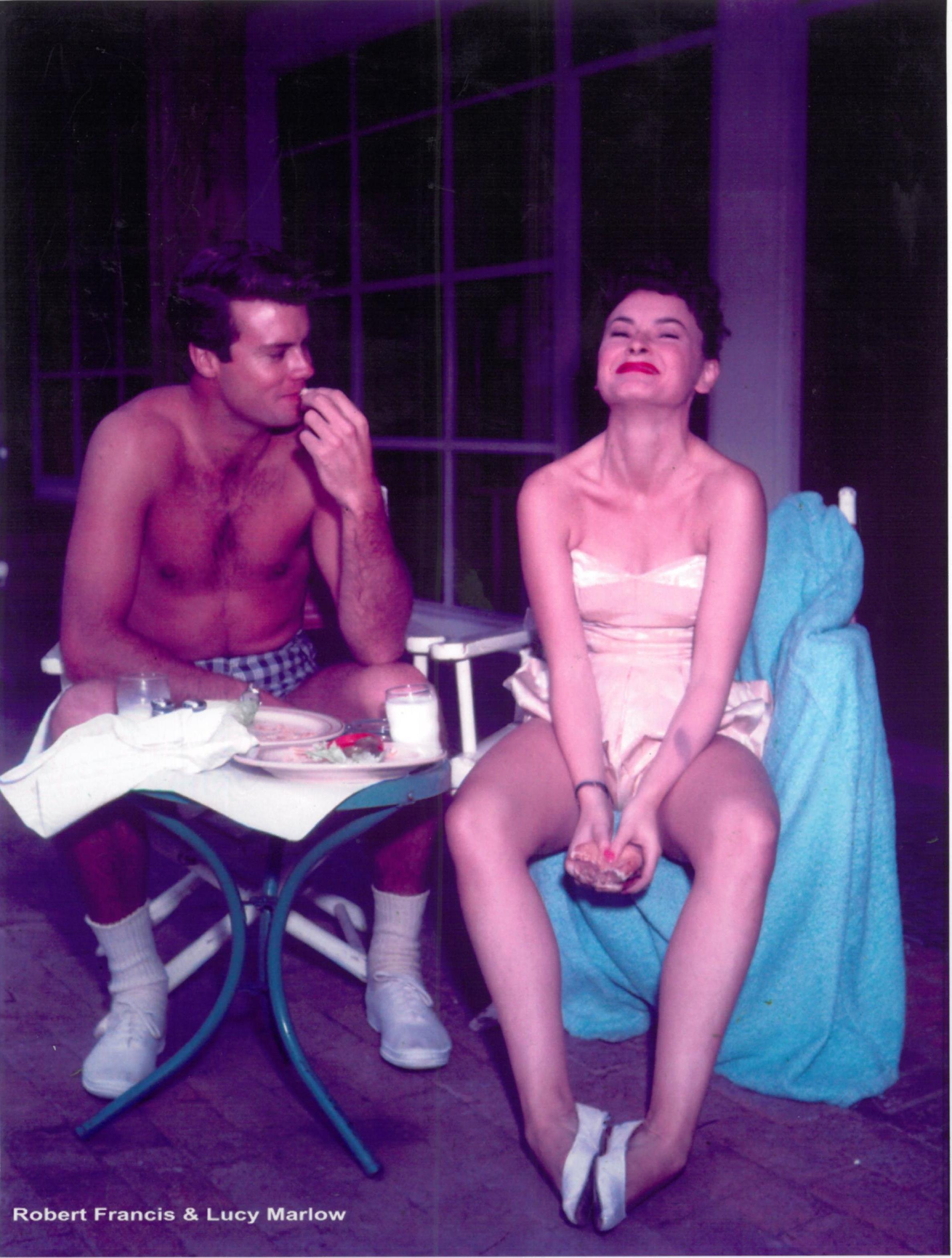

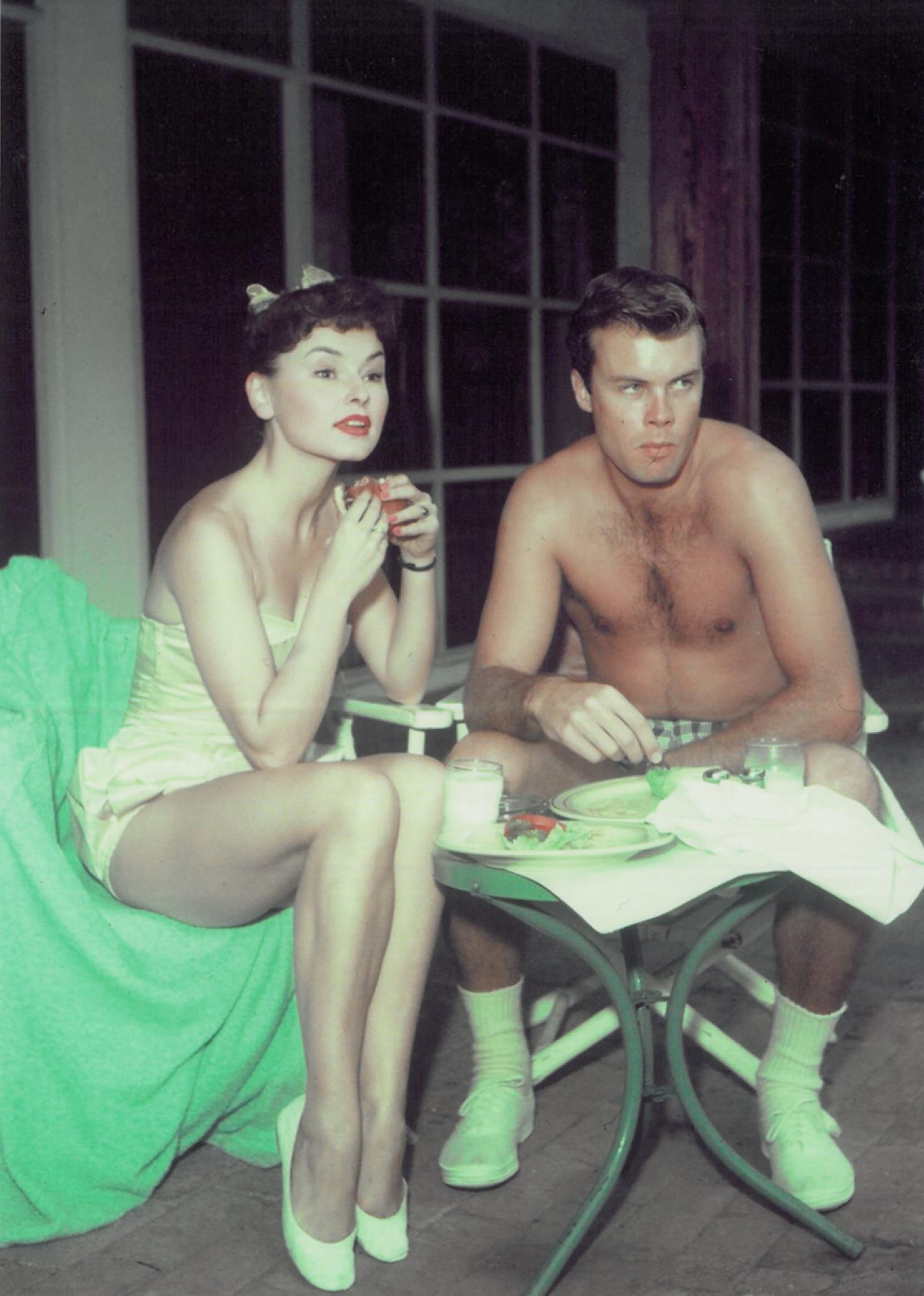

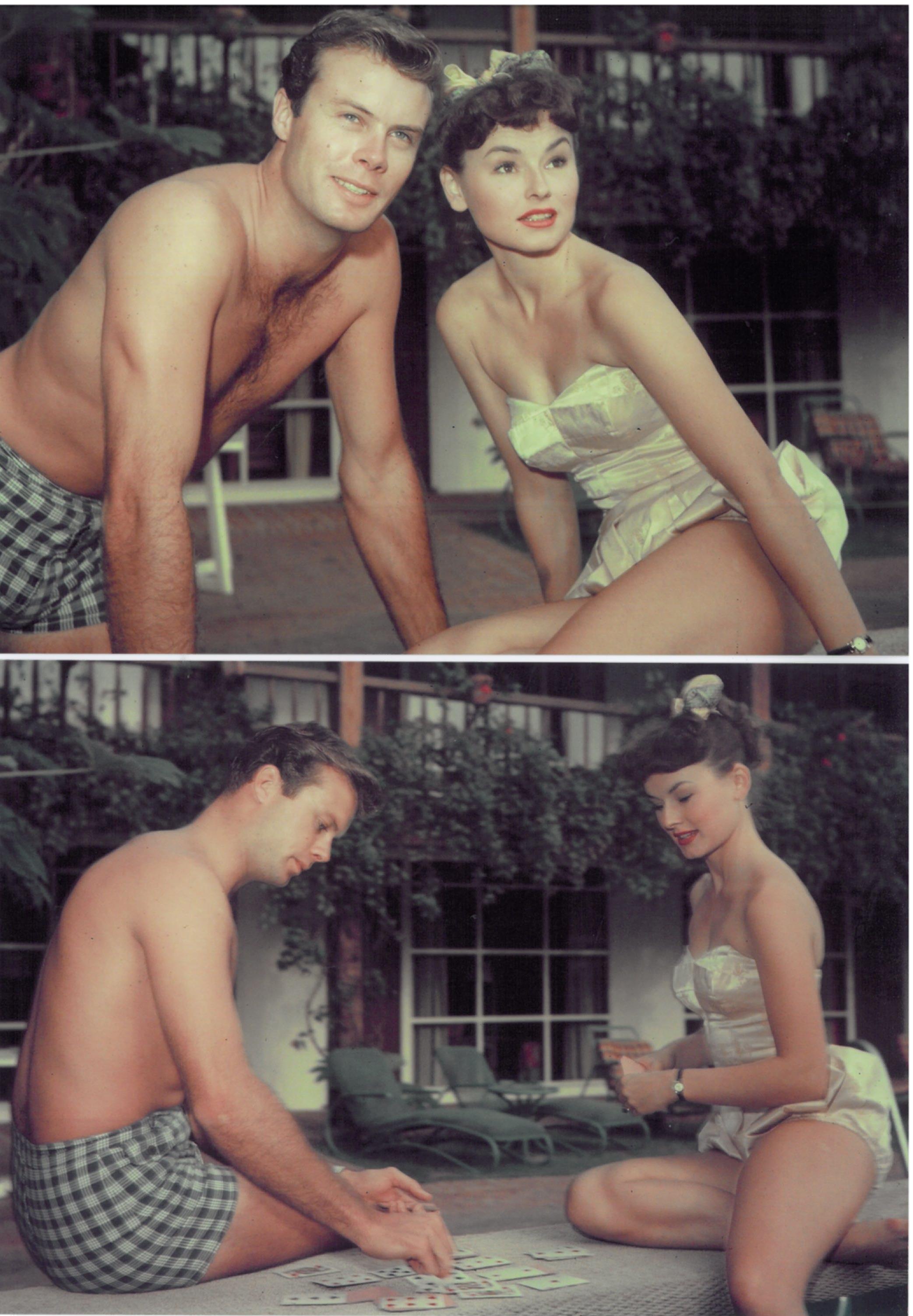

Contact sheet from photo shoot with Lucy Marlow, also a Columbia contract player. Photographer: Gene Kornman. Location: Santa Inez Inn, Santa Monica, Calif. Many of these photos appear to be outtakes. Bob’s swim trunks appear in photos made in Hawaii in 1953 and later. See The Caine Mutiny section under Films.

“…They wanted to promote the image of a carefree young stud – never my style – so I had publicity dates with your actresses around town like Lori Nelson and Debra Paget. This was a relic of the days when the studio system was in its prime. The studio would arrange for two young stars-in-waiting to go out to dinner and a dance and assign a photographer to accompany them. The result would be placed in a fan magazine. It was a totally artificial story documenting a nonexistent relationship, but it served to keep the names of young talents in front of the public. As far as I was concerned, it was part of the job, and usually pleasant enough.” (Wagner, p. 62)

Photoplay, Oct. 1954. Bob’s official biography provided basic information for Bob’s first coverage in Photoplay. Photo: Summer 1953.

Early Fall 1954

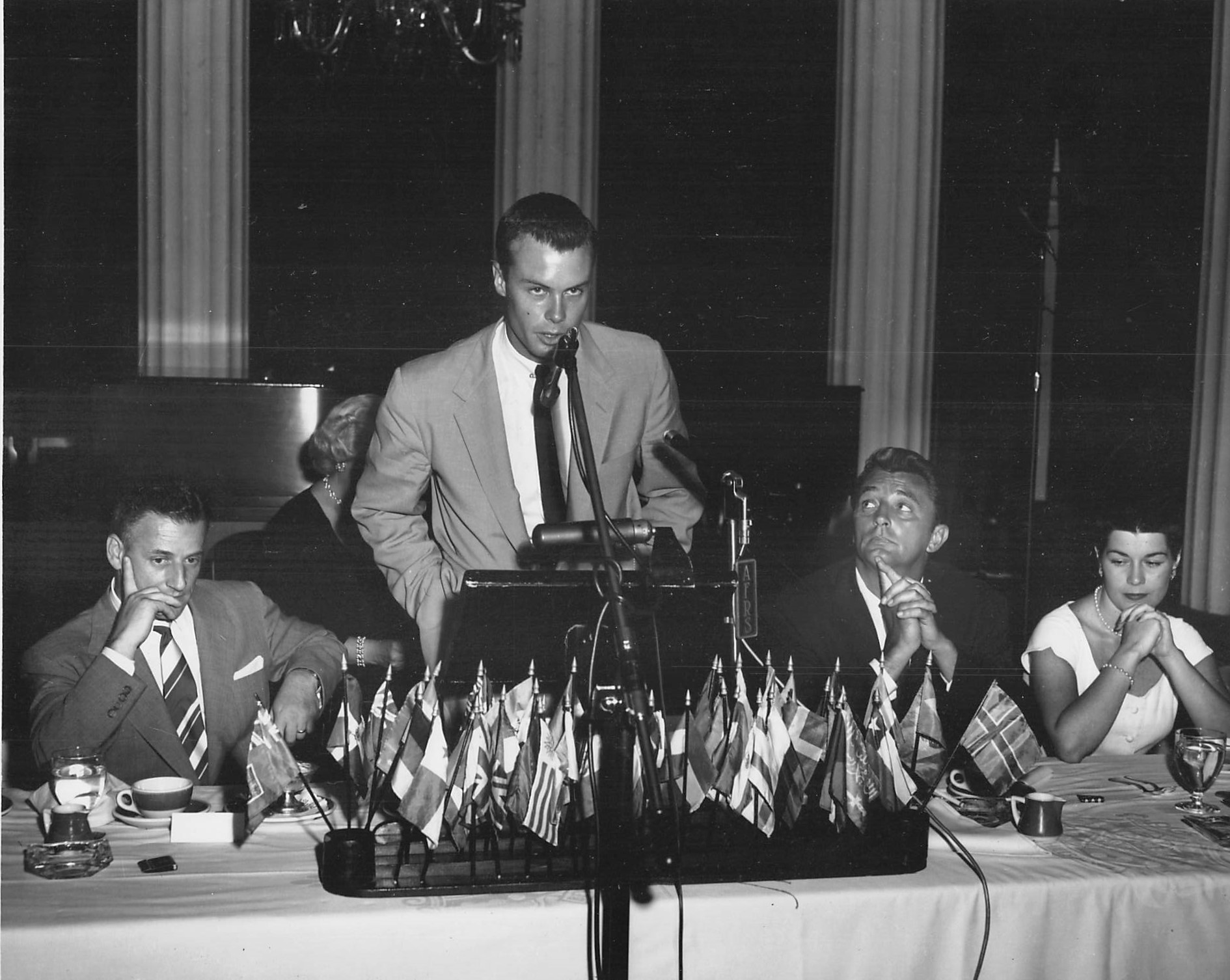

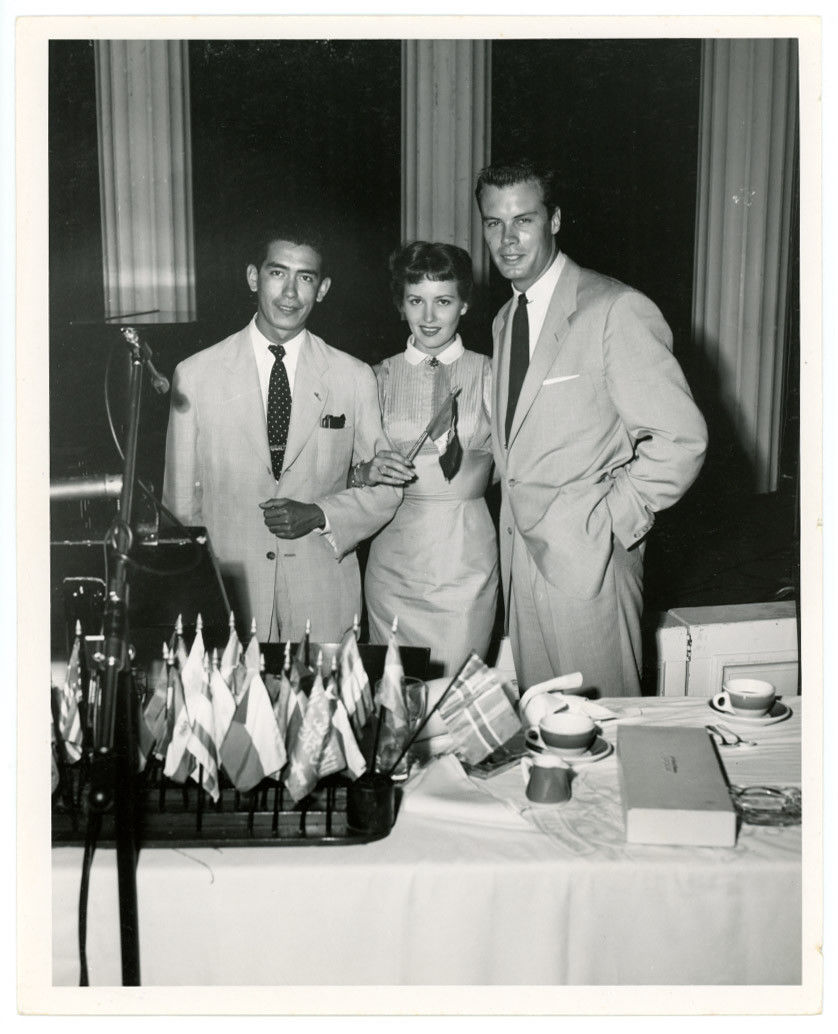

Columbia began to use Bob in various “big moments” at the studio and in Hollywood. This appears to be a luncheon event welcoming foreign dignitaries, perhaps foreign press people, to the studio. Stanley Kramer sits to Bob’s right, and Robert Mitchum to his left. The woman is unidentified. Kramer and Mitchum may have come from the set of Not As A Stranger in production, Sept. 28-mid-Dec. 1954, at Columbia (actually Kling Studios, the old Chaplin Studios on La Brea in Los Angeles).

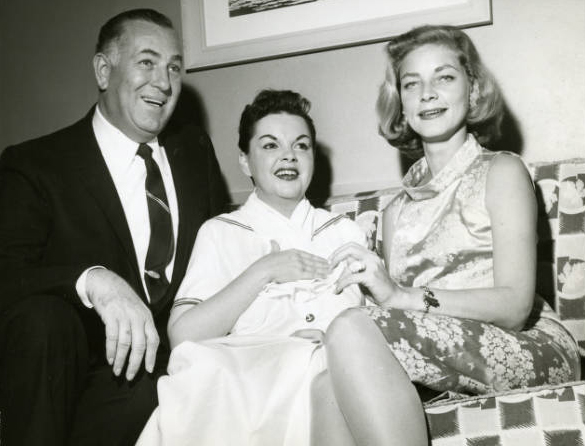

In addition to personal appearance assignments, Bob and other contract players like May Wynn attended meetings and social functions with various VIPs both in Hollywood and when touring. In Nov. 1954 Columbia hosted a meeting of foreign press representatives, including Luis Alfonso Garatea from Peru. May is holding a Peru flag. Gereghty, Columbia Pictures photographer.

Nov. 1954

Bob with Spyros Sellinas, a newspaperman from Greece. Van Pelt is Columbia Pictures photographer.

Modern Screen, Dec. 1954. Based on his haircut, most of these photos were made in Summer 1953 and/or early 1954 when he was filming The Bamboo Curtain and The Long Gray Line.

Dec. 1, 1954

Bob was probably in Hollywood in Oct. and Nov., 1954, before starting on another tour.

Bob and May Wynn in promotional photograph for American Airlines. Location: Idlewild Airport (later JFK Airport), New York City, at beginning of 15-cities in 15 days tour of New England for They Rode West. Photographer: Young for American Airlines.

Joe Hyams, Publicity Department, Columbia Pictures, New York.:

“Bob and I went to the weirdest towns. I remember Bangor, Maine — was so cold there. We went by Lincoln on a car trip all over New England. I remember 15 cities and we had a big tough guy driver in a big Lincoln. May Wynn was with us at the time. [Because of her work at the Copacabana Club in New York City in the late 1940s/early 1950s, she knew Jack Entratter* (“Mr. Entertainment”) who had been at the Copa before becoming the general manager of the Sand Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas in 1952. He took a personal interest in May’s career and often provided her with extra security when she was on the road.]

“…a very generous man. So, Mr. Entratter used to call me and say, ‘Joe, how is May?’ I’d say, ‘She is fine, Mr. Entratter. Do you need anything?’ ‘No, the studio is taking care of everything.’ Anytime we came to a town, some guy would approach us. ‘Mr. Entratter asked if you need anything.’ They were very gracious and very nice. They made jokes like, ‘Your boss [Harry Cohn] may not be giving you money.’ May was embarrassed by this.”

*Jack Entratter (Feb. 28, 1914–March 11, 1971), nicknamed "Mr. Entertainment," was an American business executive. He is best known for management positions at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City in the 1940s and early 1950s, and at the iconic Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas from the early 1950s. He is closely associated with Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack in the history of Las Vegas, Nevada. - Wikipedia

Joe Hyams, Publicity Department, Columbia Pictures, New York City:

“I remember stories of girls and drinking and bumming around like that and getting up in the morning and into that car with that driver [a tough guy who drove the loaned Lincoln for the 15 Cities/15 Days tour in New England].

“May, of course, did not join in the parties. Nor did we invite her. Poor May. She had someone in each city watching her (as a result of her relationship with Jack Entratter, general manager of The Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, and her former boss at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City).

“She would say to me, ‘Joe, please, can I come out to dinner?’ And I would say, ‘Yes.’ And she would say, ‘What are you guys doing after dinner?’ And I said, ‘May, you are going back to your room.’

“After the tour I remember getting a call from Jack Entratter, and he said, ‘I would like to show my appreciation (for taking care of May on the tour). He said, ‘I am sending some airline tickets and you will stay at The Sands Hotel.’ He said, ‘You will do it.’ I cleared it with the studio. I went out there, and I was so glad I did a good job for him. Not that I had a choice.”

Source: Joe Hyams, interview, Aug. 11, 1992

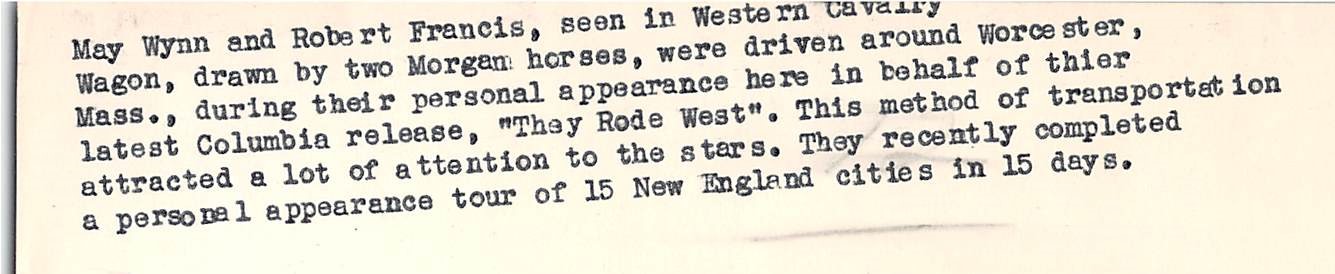

Jack Entratter, General Manager, The Sands Hotel and Casino; Judy Garland, and Lauren Bacall in Las Vegas, c. 1955.

Bob broke his schedule was when he was in New England. He took a side trip over to Lawrence Hospital in Mass. to visit the pediatric ward. His sister Lillian later worked there and somebody gave her the photograph that was made when he did that impromptu visit.

Although this candid photo by a fan is stamped JAN 55, it was probably taken in Dec. 1954 during Bob’s New England tour and later sent to Bob to autograph to “Joe,” and then returned to Joe. Bob was in New England briefly in late June 1954; he also had a 15-day tour there in Dec. 1954.

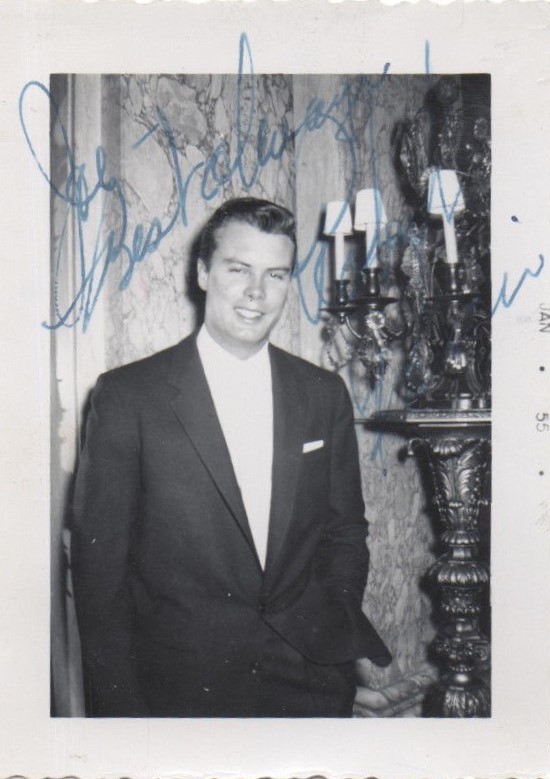

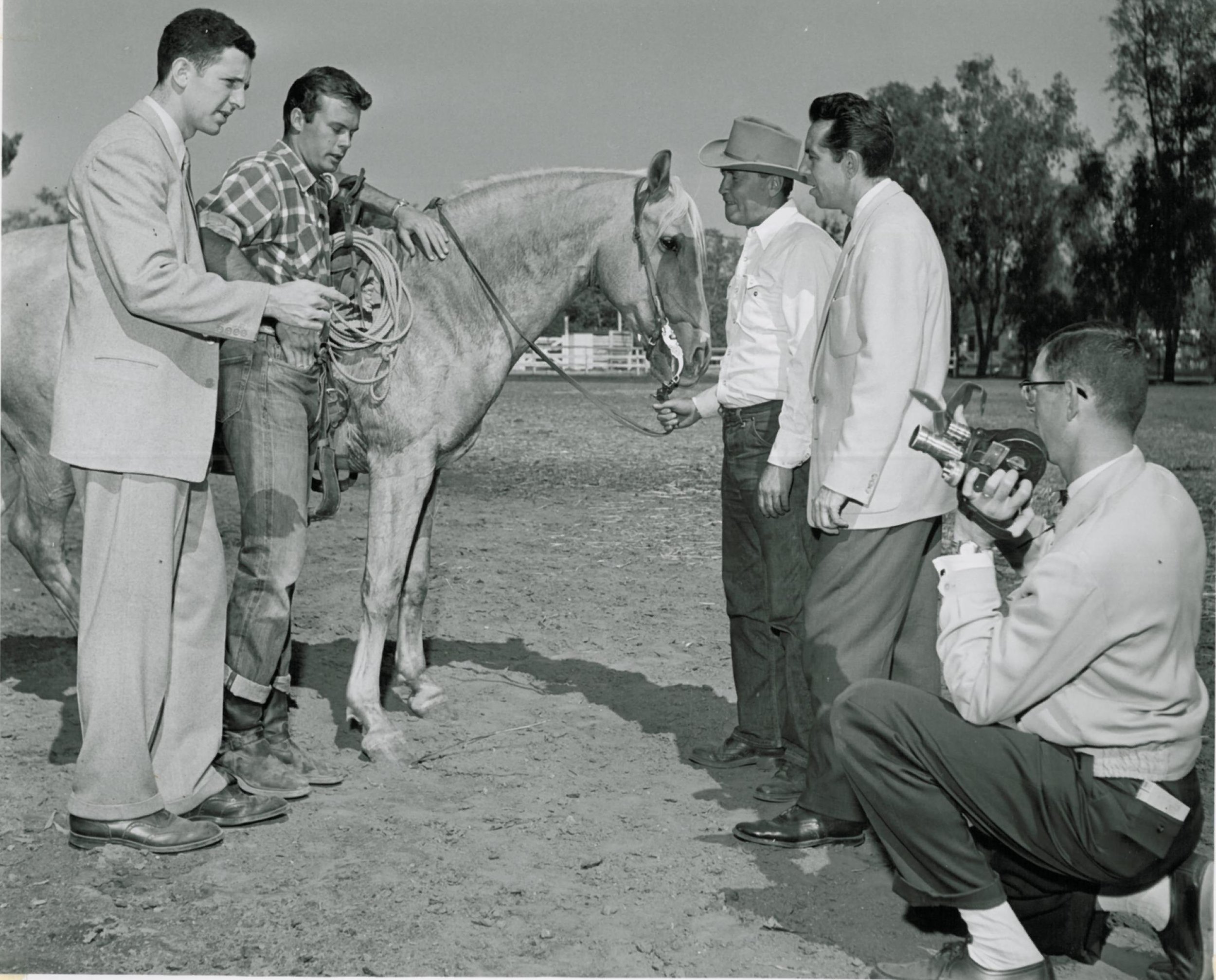

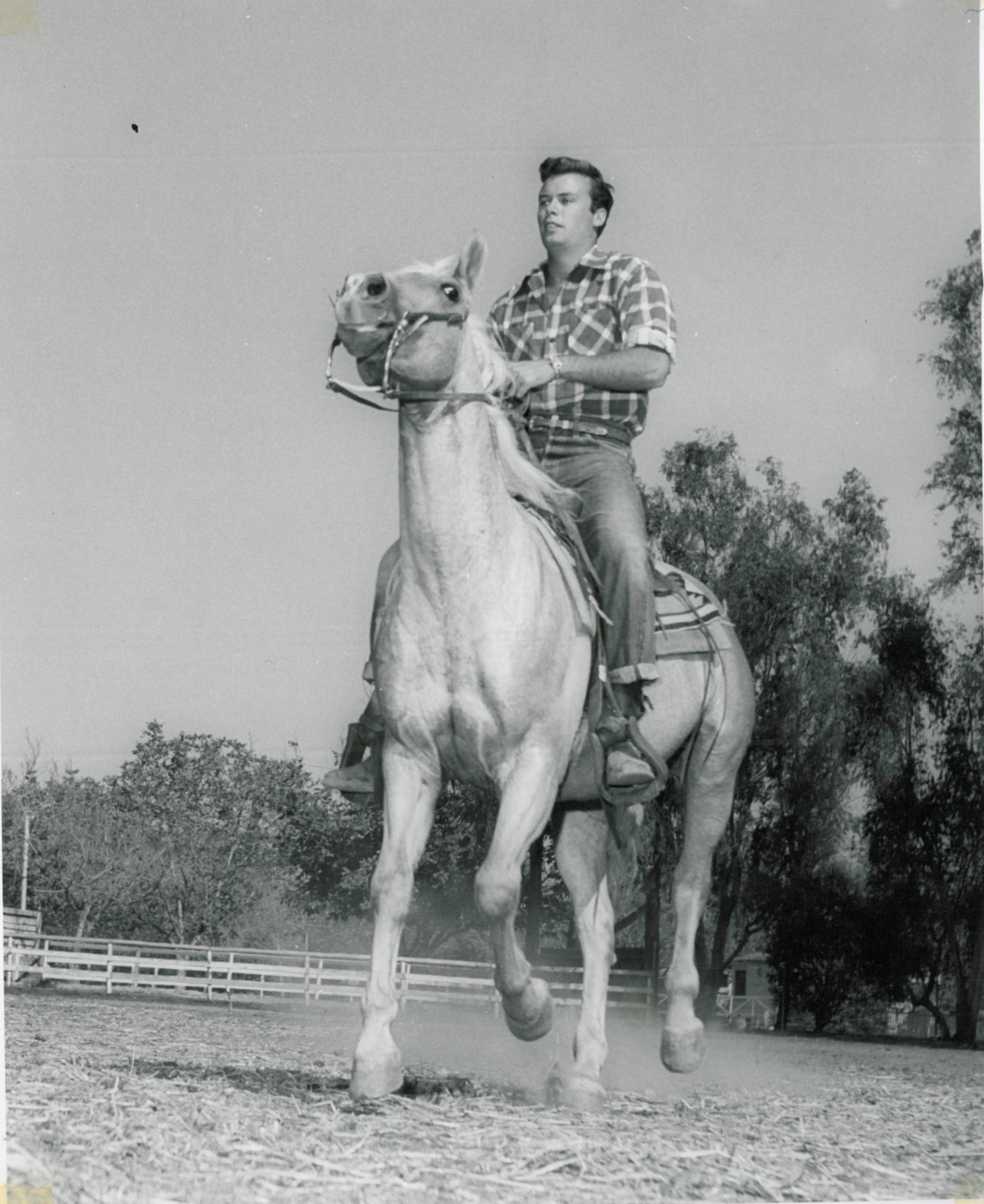

Dec. 29, 1954

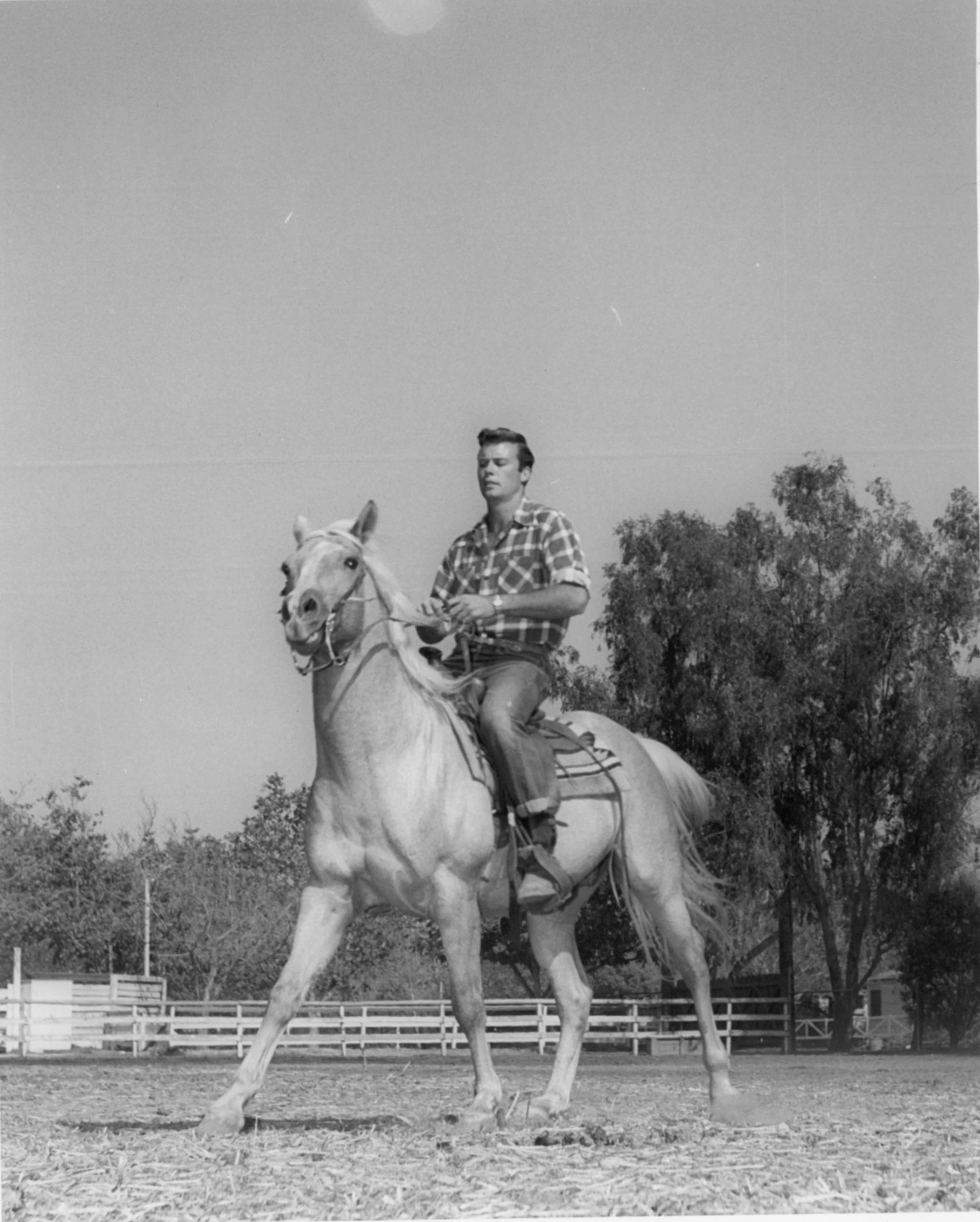

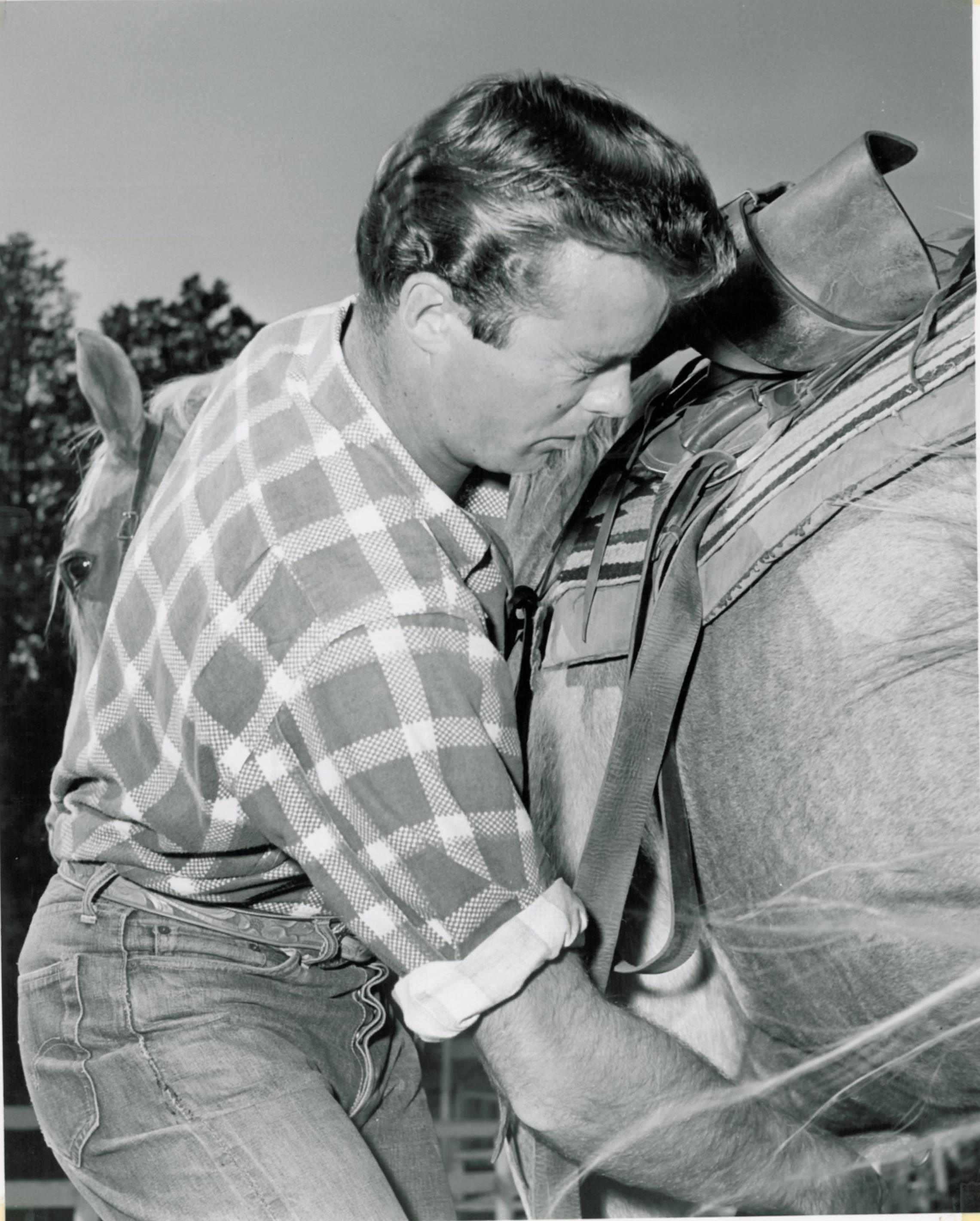

Four (4) photographs of Bob with (1) cameraman (movie) and others (unidentified) from, probably, Columbia Pictures, (2) and (3) riding the Palomino, and (4) outtake of Bob swished by horse’s tail. All photographs labeled 12-29-54,

One story states Bob was home on Dec. 23, 1954. He may have found his West Hollywood apartment during this break; he was back on the road in early Feb. to attend The Long Gray Line premieres and to promote the film.

“On one of the studio ranches he went to, there was a baby skunk. The owner sent the skunk to Bobby and said skunks would only eat raw eggs. He gave it to a friend’s son who had wild animals.”

Source: Lillian Francis Robins, interview, May 11, 1991.

Winter 1954-1955

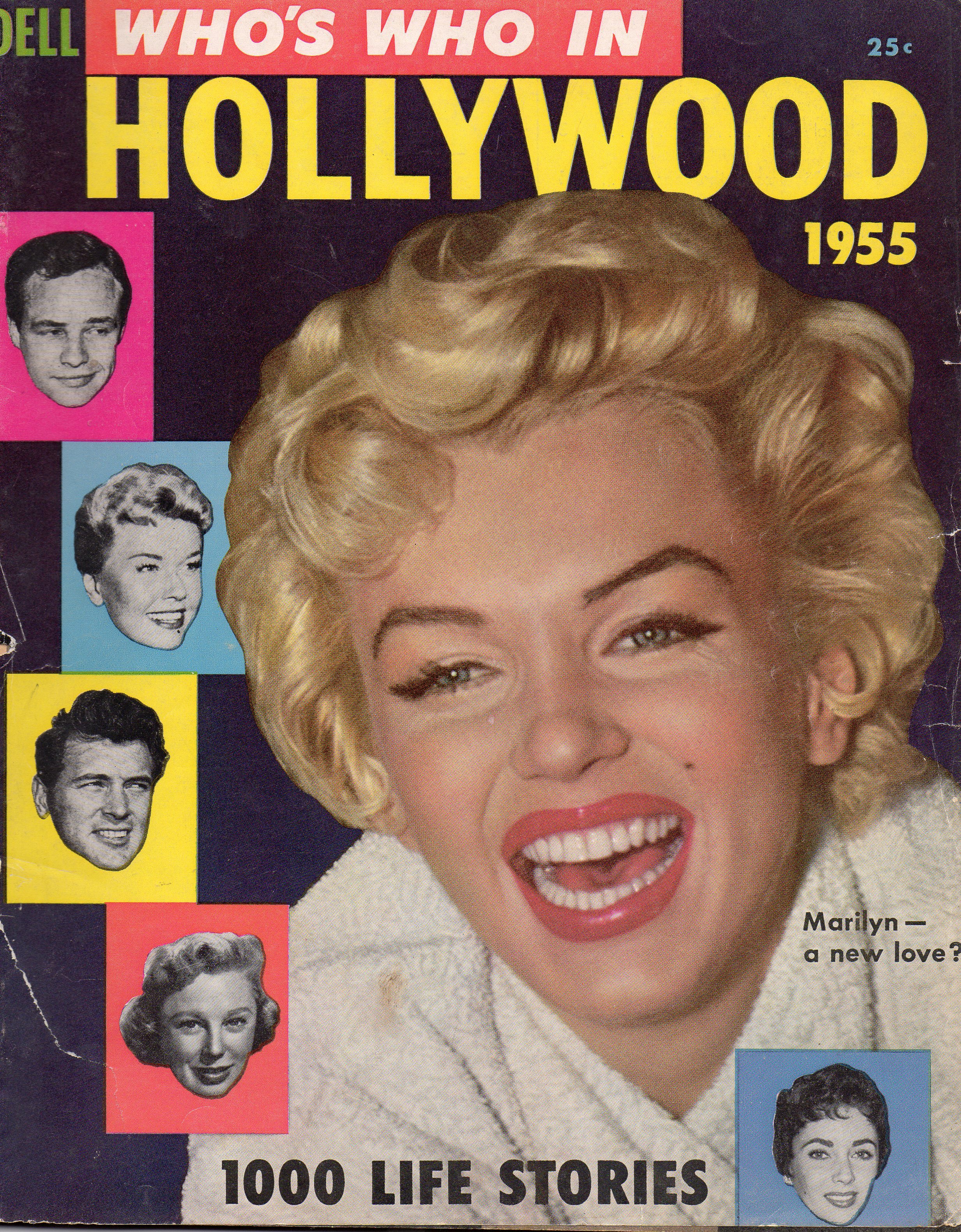

Hollywood Who’s Who 1955. Probably on newsstands in Dec. 1954/Jan. 1955. Photo taken Summer 1953.

Go to The Hollywood Star and Studio Systems - Part Two